In the 17th century, medical practices in Europe took a macabre turn. Under the belief that human body parts could cure a variety of ailments, physicians prescribed remedies made from human corpses. This practice, known as corpse medicine, promised better health through cannibalism and was endorsed by both commoners and royalty alike.

The Plight of Richard Baxter

At the age of 23, Richard Baxter, a notable writer of Protestant Christian works, suffered from a litany of health issues. His symptoms included chronic coughing, stomach pains, flatulence, joint pains, scurvy, toothaches, and persistent headaches. Desperate for relief, Baxter turned to the potent cures of his time: medicines made from human corpses.

The Rise of Corpse Medicine in Europe

Historical Origins

Baxter’s reliance on corpse medicine occurred during a period when such practices were gaining traction in Europe. The use of human body parts in medicine originated as early as the ancient Roman Empire, around the year 25. By the 1200s, the practice had become more organized and widespread, continuing in some form until the late 19th century. Physicians experimented with corpse-related remedies to treat ailments ranging from gout to severe wounds.

Medical Philosophy

The 16th-century Swiss physician Paracelsus, known as the “father of toxicology,” believed in treating ailments with substances that resembled the affliction. This philosophy influenced many corpse medicine practitioners. For instance, to prevent tooth decay, one could wear a tooth taken from a corpse, or touch it to their own.

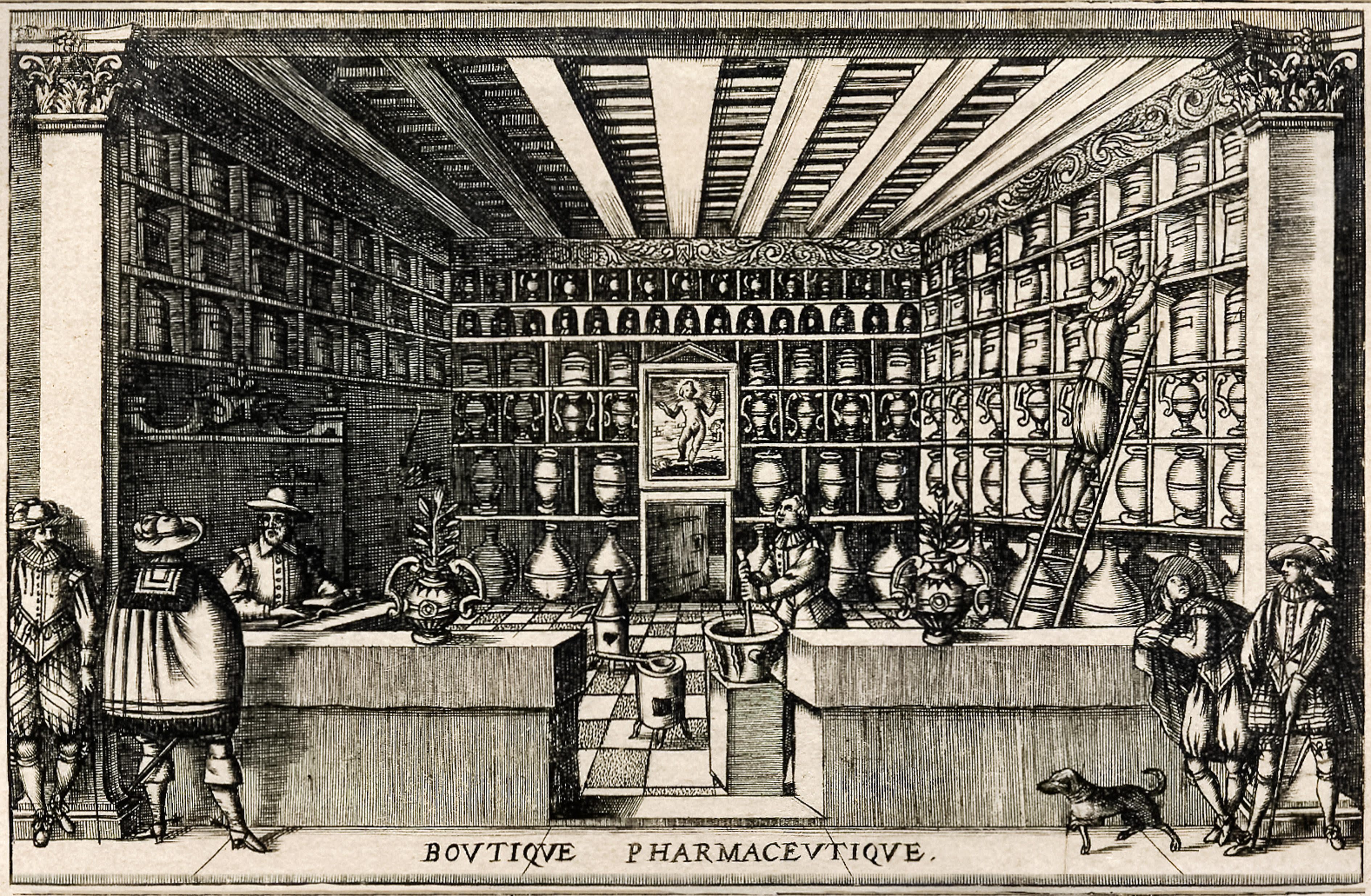

Notable Practices and Remedies

Influences from Ancient Rome

Europe’s tradition of corpse medicine has roots in ancient Rome. Medical professionals of the time recommended drinking blood directly from freshly killed gladiators. Such practices persisted through the Middle Ages and into Baxter’s era. For example, Baxter treated his bleeding episodes with moss grown on human skulls. Other remedies included “liquor of hair” for hair growth and powdered human excrement for cataracts.

Royal Endorsement

Corpse medicine was not limited to the masses; it also intrigued royalty. King Charles II of England was particularly fond of “King’s Drops,” a concoction made from powdered human skull mixed with alcohol. This remedy was believed to cure epilepsy, bleeding, and even stave off death at the last moment.

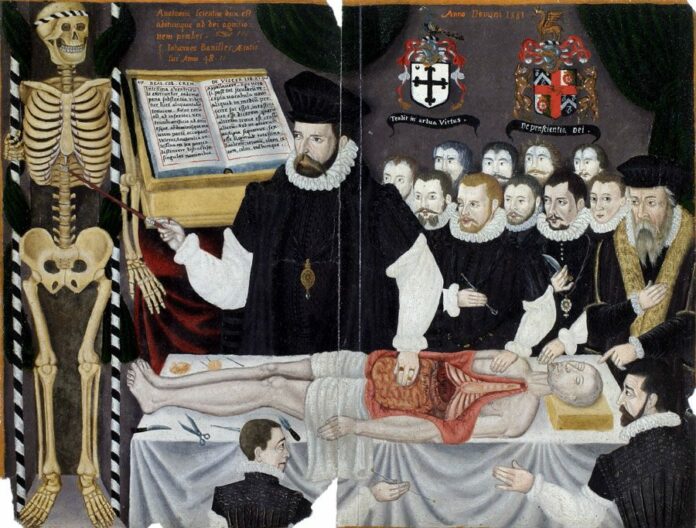

Sourcing and Preparing Human Bodies

Sources of Human Bodies

The demand for human bodies to create these medicines led to a variety of sources. Mummies were imported from Egypt, but local executions and the bodies of the poor were also common sources. Violent deaths were believed to imbue the body with particular medicinal properties. Dissection and corpse medicine became intertwined, with bodies sometimes being exhumed from graves.

Recipes for Mummy-Making

When imported mummies were scarce, local physicians created their own. Johann Schroeder, a 17th-century German physician, provided a detailed recipe for preparing a mummy from a fresh cadaver. The process involved drying the flesh with myrrh and aloe, soaking it in spirits of wine, and drying it again until it resembled smoked meat.

The Use of Every Part

Physicians utilized every part of the corpse for their remedies. Treatments for epilepsy included fingernails, skull, and mistletoe, while dried human heart and water infused with human brain were also used. Even human fat was processed and used in ointments to treat various ailments.

Contradictory Beliefs and Decline

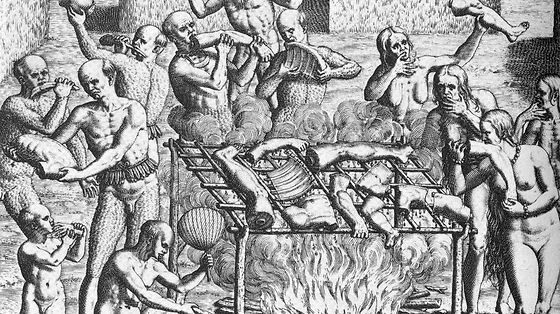

Cultural and Religious Conflicts

The practice of corpse medicine was sometimes at odds with contemporary cultural and religious beliefs. Although Europeans condemned cannibalism and used it as a justification for violence against colonized peoples, they still engaged in medical cannibalism. Protestant Christians, who opposed the Catholic Eucharist, were among those who used corpse medicine, demonstrating the complexity of human beliefs.

The Decline of Corpse Medicine

Over time, the practice of corpse medicine waned, although it persisted in some areas into the 19th century. Folk cures from this period still included substances associated with death, such as “coffin water” for warts.

Richard Baxter’s reliance on corpse medicine reflects the medical practices of his time. While modern medicine might find these practices abhorrent, we still use human body parts in medical treatments today, such as organ donation and blood transfusions. Though the methods have evolved, the underlying belief in the healing power of human body parts remains a fascinating aspect of medical history.