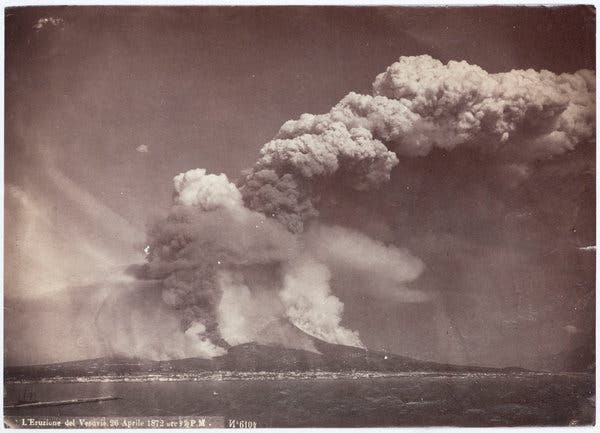

The catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D. left a haunting legacy in the Roman settlements around the Bay of Naples. Among these, Herculaneum presents a particularly grim tableau, with victims found huddled in stone boathouses, known as fornici. Two recent studies have shed new light on the fate of these individuals, challenging long-standing theories about how they met their end.

The Tragic Scene at Herculaneum

On August 24, 79 A.D., as Vesuvius erupted, the residents of Herculaneum sought refuge in the stone boathouses by the sea. Unlike Pompeii, which was buried under ash, Herculaneum was obliterated by a pyroclastic flow — a deadly, fast-moving surge of ash, gas, and rock. Since 1980, excavations have uncovered the remains of 340 people in these boathouses and on the beach.

For years, researchers have debated how these people died. A prevalent theory suggested that the intense heat vaporized their blood and brains. Some even proposed that a victim’s brain turned to glass under the extreme conditions. However, two new studies have brought fresh perspectives to this debate.

Challenging the Vaporization Hypothesis

A study published in the journal Antiquity disputes the vaporization theory. Researchers examined the bones of 152 individuals from six of the 12 boathouses. They focused on the crystal microstructures in the bones and the remaining collagen, which changes with thermal exposure. Their findings suggest that the stone boathouses and the collective body mass of the victims provided some insulation from the extreme heat, exposing them to temperatures around 500 degrees Fahrenheit — significantly lower than the maximum temperatures of pyroclastic flows.

According to Tim Thompson, a professor of applied biological anthropology at Teesside University and co-author of the study, this protection may have resulted in a slower, more agonizing death, likely by suffocation as debris and gases trapped them inside the boathouses.

The Glass Brain Hypothesis

In contrast, another study published in the New England Journal of Medicine examined a victim found in the Collegium Augustalium, a building on Herculaneum’s main street. This study claims that the intense heat vitrified the victim’s brain, turning it into glass. Pier Paolo Petrone, a forensic anthropologist at the University Federico II of Naples, attributes this phenomenon to the pyroclastic flow’s high temperatures, which caused the skull to explode.

Differing Conditions and Perspectives

Dr. Thompson explains the differences in findings as a result of the distinct environments where the victims were found. The boathouse victims were in enclosed, stone structures, while the main street victim was in a more exposed building. These varied conditions likely influenced the manner of death.

However, Dr. Petrone remains skeptical of the new findings, arguing that the study did not sufficiently consider the full range of evidence, including taphonomic and bioanthropological factors. Dr. Killgrove, a bioarchaeologist at the University of North Carolina, also questions the glass brain hypothesis, noting that the fatty acids identified could come from other sources.

A Complex Scenario

Despite these differing views, Dr. Thompson believes that both scenarios could coexist at the same site, given the complex nature of the disaster. As research continues, these studies highlight the need for renewed investigations into the causes of death at other Vesuvius-affected sites like Oplontis and Pompeii.

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius continues to intrigue and horrify us, as new research challenges our understanding of the tragic events that unfolded. While the debate over how the victims of Herculaneum died persists, these studies underscore the importance of revisiting and re-evaluating historical evidence. As we uncover more about these ancient tragedies, we gain deeper insights into the lives and deaths of those who faced the fury of Vesuvius.