he Morobe Province in Papua New Guinea is inhabited by the Anga people, who were once known as formidable warriors, conducting raids on neighboring peaceful villages. However, in recent times, the Anga have found a unique way to capitalize on tourism. Visitors such as anthropologists, adventurers, and curious travelers are drawn to the remote villages of the Morobe Highlands to witness the renowned smoked mummies that the Anga are famous for.

The allure of these smoked mummies has transformed the once-feared warriors into hosts of a peculiar form of tourism. The isolated villages of the Morobe Highlands have become a destination for those seeking to experience the cultural and historical significance of the Anga people’s preserved ancestors. The smoked mummies act as a bridge between the past and the present, allowing visitors to witness firsthand the ancient practices of mummification and gain insights into the traditions, beliefs, and way of life of the Anga.

This unique form of tourism not only provides economic opportunities for the Anga people but also serves as a means of cultural exchange, fostering a greater understanding and appreciation of their rich heritage. It is a testament to the enduring fascination that ancient practices, such as mummification, hold for people from diverse backgrounds who seek to unravel the mysteries of the past and connect with the living legacies of unique cultures like the Anga.

The exact origins of the practice of smoking mummies among the Anga people in Papua New Guinea are not definitively known. However, it is believed to have been in existence for at least 200 years. The act of smoking mummies was officially banned in 1975 when Papua New Guinea gained independence. As a result, the most recent mummies that can be observed today date back to the years following the Second World War. These mummies offer a glimpse into a relatively recent period of Anga history and represent an important cultural and historical legacy for the community. The prohibition of the practice underscores the evolving cultural landscape of Papua New Guinea and the impact of external influences on traditional customs and rituals.

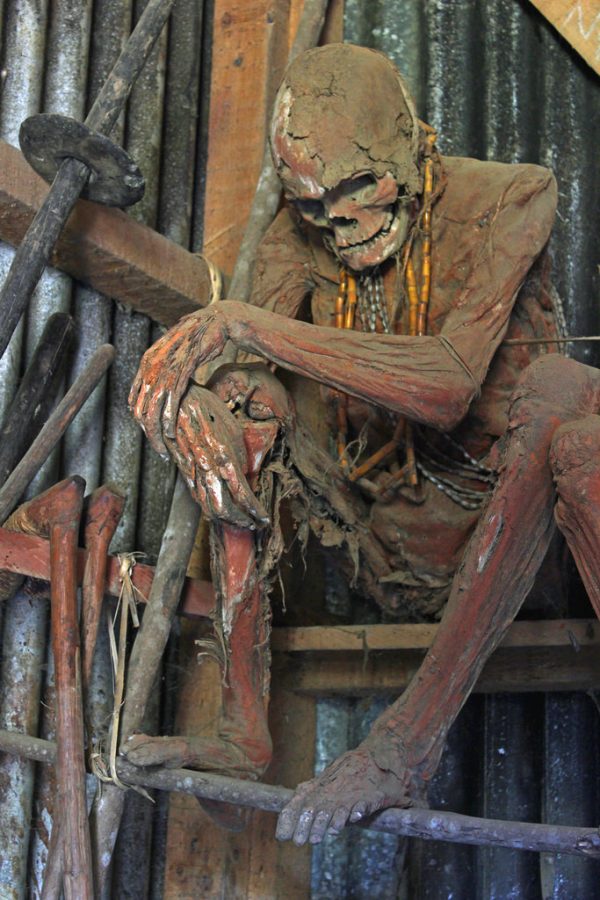

The treatment of honor bestowed upon the most valiant warriors among the Anga people involved a series of rituals after their death. Once they passed away, their bodies underwent a specific preservation process. Firstly, they were bled dry and disemboweled, after which they were placed over a fire to begin the curing process. The smoking could continue for an extended period, sometimes lasting over a month. During this time, the body gradually dried out.

Once the body was completely dry, all bodily cavities were sewn shut, and the entire corpse was coated with a mixture of mud and red clay. This application served two purposes: to enhance the preservation of the flesh and to create a protective layer against insects and scavengers.

Regarding the claim that the fat derived from the smoking process was saved for later use as cooking oil, there is some uncertainty. It is possible that this detail arose from the accounts of early explorers, like Charles Higgingon, who reported on the mummies in 1907. It is worth noting that when Westerners encountered remote and “primitive” tribes, there was often a tendency to sensationalize or misinterpret cultural practices, sometimes attributing cannibalism where it did not exist.

It is important to approach historical accounts with critical analysis, considering the context in which they were documented and the potential biases of the observers. While the preservation techniques and rituals surrounding the Anga smoked mummies are well-documented, some specific details, such as the use of the fat, may require further verification and examination.

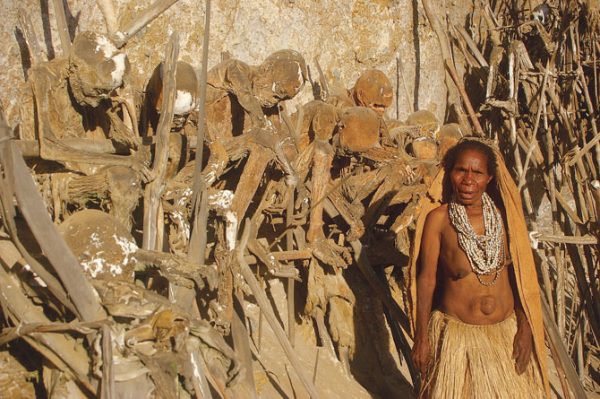

Following the ritual ceremony, the preserved bodies of the Anga warriors were transported and positioned on mountain slopes that overlooked their village. Bamboo structures were used to securely attach the mummified remains to the steep rock face. By placing the smoked mummies in such elevated positions, they were intended to serve as lookouts, guarding and protecting the dwellings in the valley below. This unique practice allowed the deceased warriors to maintain their esteemed warrior status even in death, symbolically watching over their community and perpetuating their protective role beyond their mortal existence. The placement of the mummies in strategic locations demonstrated the significance and reverence accorded to these honored individuals within their society.

In the present day, the smoked bodies of the Anga warriors continue to be venerated and revered. There are instances where the mummified remains are brought back to the village for restoration purposes. During this process, the descendants of the deceased individuals undertake the task of changing the bush rope bandages that hold the remains together. They also ensure that the bones are securely fastened to the sticks before returning the ancestor to their designated lookout post.

This ongoing ritual of restoring and maintaining the mummies demonstrates the deep connection and respect that the Anga people have for their ancestors and their warrior heritage. By actively engaging in the preservation and upkeep of the mummified bodies, the descendants honor the memory and legacy of their forefathers. It is a testament to the enduring cultural traditions and the continued significance of these ancestral figures within the community. The act of bringing the mummies back to the village for restoration reinforces the bond between the living and the deceased, symbolizing the ongoing presence and influence of the ancestors in the lives of the Anga people.

Despite the mummies being mainly those of village warriors, as mentioned, among them are sometimes found the remains of some woman who held a particularly important position within the tribe. The one in the following picture is still holding a baby to her breast.

Indeed, the preservation method described for the Anga mummies bears similarities to other cultural practices found in different parts of the world. The Toraja funeral rites in Indonesia and the “fire mummies” in Kabayan, Philippines, share certain aspects with the Anga mummification process.

In the case of the Kabayan fire mummies, the bodies were placed over a fire to dry while curled in a fetal position. Tobacco smoke was blown into the mouth of the deceased to aid in the preservation of internal organs. After preparation, the mummified bodies were placed in pinewood coffins and laid to rest in natural caves or specially dug niches within the mountains. This practice aimed to ensure the integrity of the ancestor spirit, allowing them to continue protecting the village and ensuring its prosperity.

These cultural practices highlight the significance placed on the preservation of ancestors and the belief in their continued presence and influence within the community. The use of specific preservation techniques, such as smoking and careful positioning, emphasizes the connection between the living and the deceased, as well as the ongoing role of the ancestors in maintaining the well-being of the community.

While these practices may appear peculiar from an outside perspective, they provide valuable insights into the cultural, spiritual, and social dimensions of these societies and their beliefs surrounding death, ancestry, and community protection.

The examples you’ve mentioned, such as the Palermo Catacombs and the Anga mummies, highlight the enduring belief in the connection between the living and the deceased, as well as the ongoing role of ancestors within their respective communities.

In the case of the Palermo Catacombs, the preserved mummies provided a tangible link to the afterlife. Visitors, including young boys, could interact with these mummified ancestors, learn about their family history, and seek their guidance and benevolence. This practice reinforced the idea that death was not a definitive separation but rather a transition, allowing for ongoing communication and connection between the realms of the living and the deceased.

Similarly, among the Anga people, the presence of the mummified ancestors on the mountain slopes serves as a reminder of their continued importance within the community. When an Anga man points to a specific mummy and declares, “That’s my grandpa,” it underscores the notion that the deceased maintain their distinct identities and roles even after death. This recognition further emphasizes the relevance and significance of ancestral figures in the lives of the living.

Both examples demonstrate the belief in an ongoing interchange between the two realms and the understanding that death does not erase the personality or influence of the deceased. Rather, it reinforces their continued presence and impact within the community, allowing for a connection and exchange that transcends the boundaries of life and death.