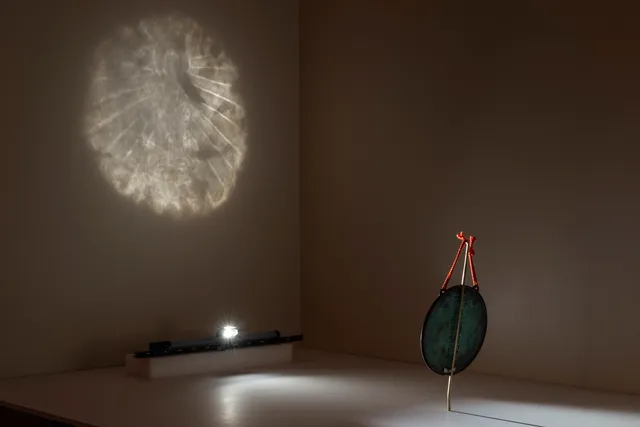

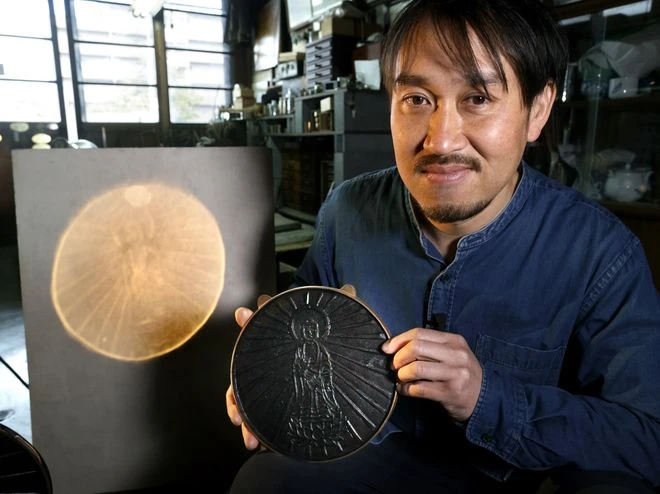

In a remarkable twist, a seemingly ordinary handheld mirror from the Cincinnati Art Museum’s collection of East Asian art has revealed an astonishing secret. Thought to be a bronze looking glass with an inscription of the Amitābha Buddha, the mirror has recently been found to project a mystical image of a Buddha surrounded by radiant light when illuminated with a bright light. This unexpected discovery was made by Dr. Hou-Mei Sung, the museum’s curator of East Asian art, and has left experts intrigued.

The mirror, believed to date back to the 16th century, is an example of a “magic mirror” known as 透光鏡 (tòu guāng jìng) in Chinese, or light-penetrating mirror. These mirrors were crafted in China and Japan during that period. Starting from July 23, the mirror will be on permanent display in the East Asian galleries of the museum.

Dr. Sung’s interest in the mirror was piqued while researching Buddhist objects for a gallery rehang. She learned about Buddhist magic mirrors, which commonly featured the inscription “Hail to Amitābha Buddha” on the reverse side. Curiosity led her to ask the museum’s object conservator to shine a light on the back of the mirror, hoping to reveal its hidden nature. To their astonishment, they discovered that the mirror indeed projected a concealed image of the Buddha.

The mirror was officially acquired by the museum in 1961, but its exact history and significance remain elusive due to the lack of comprehensive records. Dr. Sung has been piecing together its background by examining other known examples of magic mirrors. However, due to their enigmatic nature, few have been identified. Notable examples include those held by the Tokyo National Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, both featuring the same six-character chant to Amitābha in simplified Chinese characters. The Cincinnati Art Museum’s mirror, in contrast, uses traditional characters, indicating its likely origin in China.

According to Dr. Sung, the origins of magic mirrors can be traced back to the Han Dynasty in the second century BCE. Initially, people used small mirrors to reflect decorative patterns onto walls. These early designs were traditional and served ritualistic purposes. The curator believes that the Buddhist versions emerged during the Ming Dynasty and were likely used for worshiping Amitābha. Adherents would chant the invocation in hopes of rebirth into the Western Paradise after death. The sophistication of these mirrors is evident, as their projected designs are invisible on the reflective surface.

Scholars have been studying the craftsmanship of magic mirrors since the seventh century. One theory suggests that makers deliberately polished the backs of the mirrors to create intricate marks that manipulate the incoming light. Modern research indicates that these mirrors consist of two metal discs soldered together, with the Buddha image sealed within the mirror on the back side of the front surface. Reproducing this intricate technique today would be a formidable challenge.

When the mirror goes on display, the Cincinnati Art Museum plans to illuminate the hidden Buddha by shining a light on its reflective surface. Visitors will have the opportunity to observe both the concealed image and read the Amitābha inscription, creating a captivating experience that showcases the mirror’s magical nature.

The discovery of the hidden Buddha in the 16th-century ‘magic mirror’ adds a new layer of intrigue to the Cincinnati Art Museum’s collection of East Asian art. It serves as a reminder of the rich cultural heritage and the mysteries that can still be unearthed from seemingly ordinary objects.