Archaeology continues to uncover fascinating glimpses into the medical practices and rituals of ancient civilizations. The latest discovery from Crimea is no exception, as researchers have unearthed the skull of a 5,000-year-old man who underwent an unsuccessful brain surgery procedure.

The Remarkable Discovery

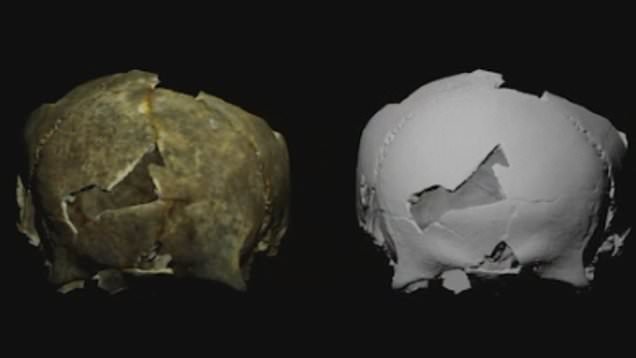

Archaeologists have unearthed the skull of a 5,000-year-old man who underwent ancient brain surgery. Remarkable 3-D imagery and pictures from Crimea show traces of trepanation, a surgical procedure to create an opening in the skull, on a Bronze Age man aged in his 20s.

The surgery was not successful, say scientists, and the ‘unlucky’ patient lived only a short time after going under a stone ‘scalpel’. ‘The ancient ‘doctor’ definitely had a “surgical set” of stone tools,’ said the Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow.

According to the Institute of Archaeology, the position of the bones indicates the body of the deceased was deliberately and thoughtfully positioned. The skeleton was lying on its back, slightly turned onto the left side. The legs were strongly bent at the knees and angled to the left.

Burial Artifacts

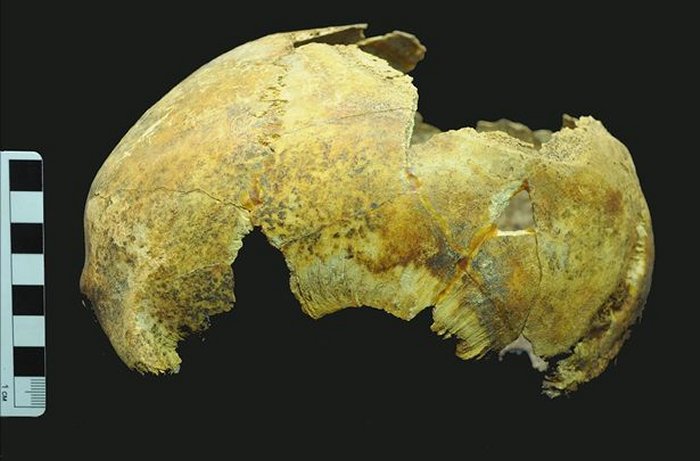

Alongside the skeletal remains, the archaeologists also discovered large fragments of red pigment near the head and covering the top of the skull vault. Additionally, two flint arrowheads were found buried with the ancient man.

This meticulous burial treatment and the inclusion of symbolic artifacts suggest this individual held a significant status within their Scythian community. The careful positioning of the body and the use of red pigment were likely part of cultural burial rituals practiced during this time period.

Insights into Ancient Medical Practices

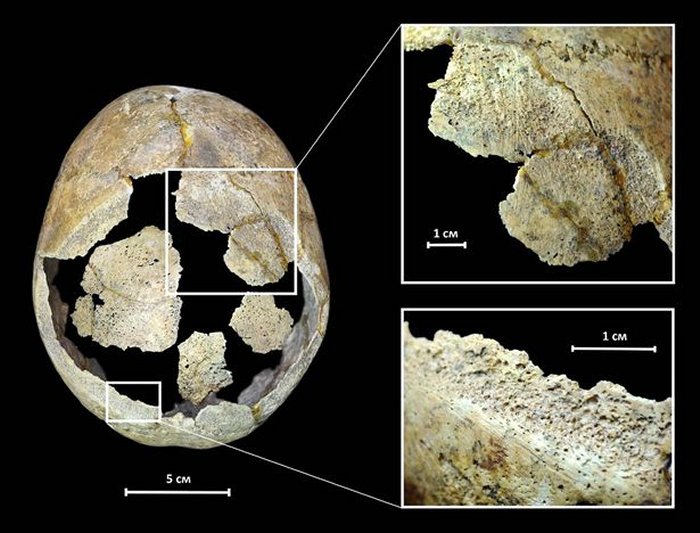

Two flint arrowheads were buried with the ancient man. The dimensions of the trepanation were 140 × 125 millimetres. Dr Maria Dobrovolskaya, head of the Laboratory of Contextual Anthropology, said: ‘This young man was unlucky. Despite the fact that the survival rate after trepanation was very high even in ancient times, he apparently died shortly after the surgery.’

Three types of marks were left by the prehistoric ‘surgeons’ using different kinds of stone blades, said Olesya Uspenskaya, a researcher in Stone Age archeology. These were small long linear tracks, large deep linear traces in the form of parallel grooves, and marks left with a thick blade.

Experts believe trepanation in ancient times was carried out for both surgical and ritual purposes. The aim of brain surgery in ancient times may have been to ease severe headaches, cure a haematoma, repair skull injuries, or seeking to overcome epilepsy. This remarkable discovery sheds new light on the medical knowledge and practices of our ancient ancestors.