In the vast desert of southern Arizona, a remarkable relic has come to light: a bronze hackbut cannon, buried for nearly five centuries. This artifact, the oldest firearm ever discovered in the continental United States, tells a story of conquest, resistance, and survival. Unearthed at the site of San Geronimo III, a short-lived Spanish settlement, the cannon serves as a silent witness to one of the earliest Native American victories over European colonizers.

The Hackbut Cannon: A Revolutionary Weapon

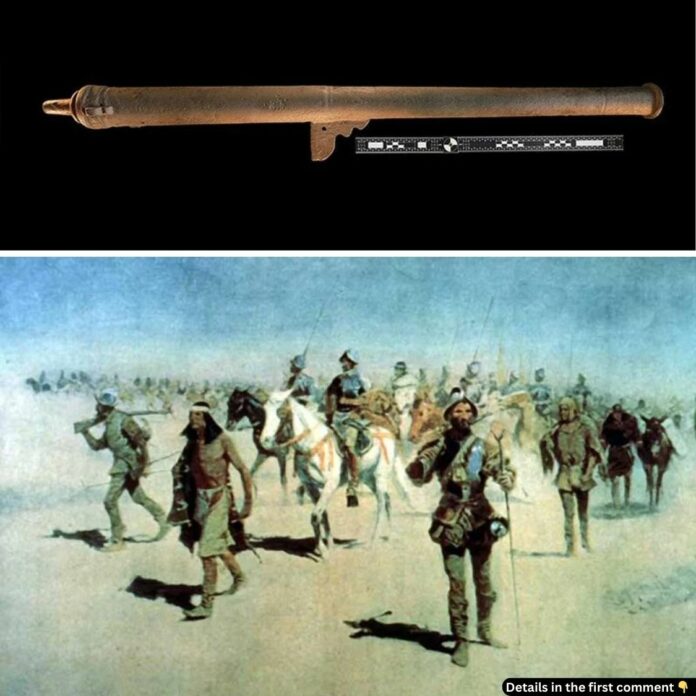

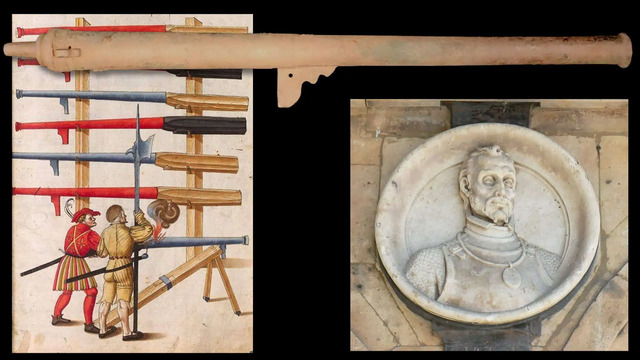

The 40-pound hackbut cannon, unearthed from the ruins of a collapsed building, offers a glimpse into the engineering ingenuity of early modern weaponry. Designed for portability, it featured a robust wooden tripod that allowed for quick disassembly and easy transport across rugged terrain. Its lightweight structure and practical design made it ideal for expeditions like Francisco Vázquez de Coronado’s, where firepower and mobility were essential.

Capable of firing a 4-ounce load of buckshot or a single lead ball up to 700 yards, the cannon was intended to intimidate and devastate. However, it lacked precision, as evidenced by its flat ledge near the touch hole instead of sights. Operated by igniting priming powder with a slow-burning match cord, the weapon was as loud as it was terrifying—designed more for psychological impact than accuracy.

Yet this particular cannon, its barrel free of black powder residue, tells a haunting story: it was never fired in battle.

Video:

Coronado’s Expedition and the Settlement of San Geronimo III

In 1540, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado embarked on an ambitious journey northward from Mexico, seeking the fabled “Seven Cities of Gold.” Accompanied by 400 soldiers, their families, and 1,500 Indigenous allies, the expedition was grueling. Crossing mountains and deserts, the group faced extreme hardships, relying on limited water and supplies.

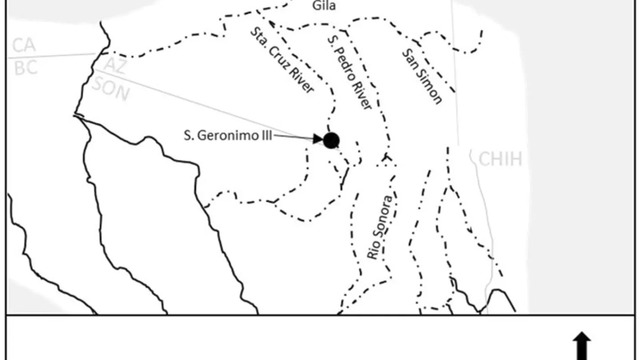

By 1541, Coronado’s expedition reached what is now southern Arizona and established San Geronimo III, or Suya—the first European settlement in the American Southwest. This settlement, fortified with adobe and rock structures and protected by weapons like the hackbut cannon, was meant to be a permanent foothold for Spain in the region.

However, the Sobaipuri O’odham, the local Indigenous people who farmed the area, soon clashed with the newcomers. The Spanish conquistadors, in their quest for dominance, enslaved women, seized food, and meted out brutal punishments for dissent, such as cutting off noses and hands. These abuses fueled tensions, setting the stage for a dramatic uprising.

The Fall of San Geronimo III

In the predawn hours of a fateful morning in 1541, the Sobaipuri O’odham launched a surprise attack on San Geronimo III. The settlers, caught off guard, were unprepared to defend themselves. Historical accounts differ on the details, but the outcome was devastating for the Spanish. Many were killed in their sleep, and the survivors fled in chaos.

One account mentions a priest wielding a broadsword in a desperate attempt to protect the settlement, managing to save six people. Despite its advanced design, the hackbut cannon remained unused—its intended purpose of intimidation and protection rendered moot by the speed and ferocity of the Indigenous assault.

The battle marked a significant victory for the Sobaipuri O’odham, forcing the Spanish to abandon their settlement and delaying colonization efforts in the region for over a century.

The Cannon’s Discovery and Preservation

The hackbut cannon was discovered in the ruins of a collapsed building by archaeologist Deni Seymour. Buried under layers of mud and rock, it was remarkably well-preserved, thanks to the protection of the fallen structure.

Analysis revealed that the cannon, though obsolete by the 1540s, was likely cast in Mexico decades earlier. Metallurgical studies showed a lack of lead in the bronze, consistent with casting techniques used during Hernán Cortés’ conquest of the Aztec Empire. This detail suggests the cannon may have been repurposed from an earlier campaign.

A Rare Victory Against Conquest

The events at San Geronimo III represent a rare and significant Native American victory over European forces. The Sobaipuri O’odham’s success delayed Spanish colonization in the region, underscoring the resilience and determination of Indigenous peoples in the face of conquest.

Artifacts recovered from the site paint a vivid picture of the battle. Alongside the cannon, archaeologists found crossbow bolts, chainmail fragments, and broken swords—evidence of the settlers’ desperate last stand. These relics, combined with historical accounts, provide a deeper understanding of the clash between European colonizers and Native Americans.

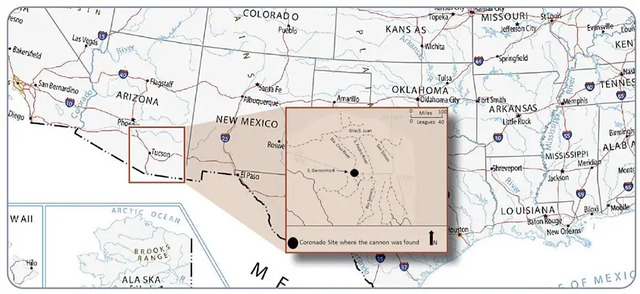

Rewriting Coronado’s Route

The discovery of the hackbut cannon has also reshaped historians’ understanding of Coronado’s expedition. For years, the exact route of the journey was debated, relying on vague journal entries and speculative analysis of the terrain. Now, artifacts like the cannon and other items found at San Geronimo III, such as 16th-century nails and pottery, anchor Coronado’s path with much greater accuracy.

Additionally, Seymour and her team have identified four more campsites along Coronado’s trail, using a combination of historical research and modern archaeological methods. These discoveries continue to illuminate the hardships and strategies of the expedition.

The Legacy of the Hackbut Cannon

The hackbut cannon is more than just a piece of military history—it is a symbol of resistance and resilience. It tells the story of a community that fought to protect its land and culture against a powerful and technologically advanced adversary.

Today, the cannon stands as a reminder of the complexities of conquest and colonization. It represents the meeting of two worlds—one seeking to dominate and the other striving to survive—and highlights the often-overlooked narratives of Indigenous resistance in history.

Conclusion

The discovery of the 500-year-old hackbut cannon is a remarkable window into a pivotal moment in American history. It bridges the past and present, offering insights into the technological ingenuity of the Spanish, the resilience of the Sobaipuri O’odham, and the lasting impact of their clash.

As more artifacts are uncovered and studied, the story of San Geronimo III continues to unfold, enriching our understanding of the early encounters between Europe and the Americas. In the silent barrel of the cannon lies a powerful reminder: history is not just about conquest but also about the courage and resistance of those who fought to defend their homes.