The Complex History of the Dresden Codex: Deterioration, Transcription, and Pagination

Agostino Aglio’s Pioneering Transcription

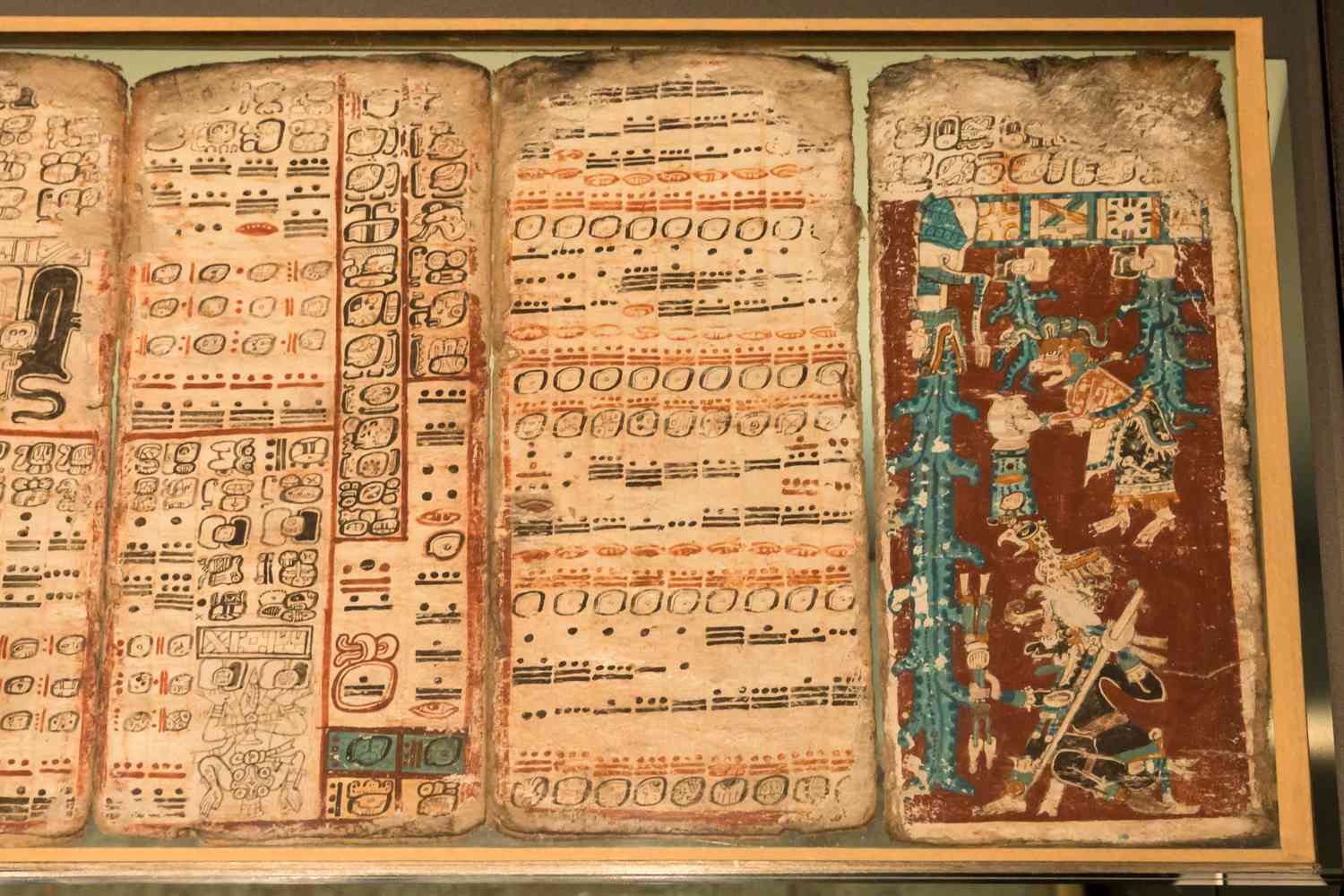

The Dresden Codex, one of the most significant pre-Columbian Maya texts, has a long and complex history. In 1826, the Italian artist and engraver Agostino Aglio became the first person to comprehensively transcribe and illustrate the entire codex. Aglio’s work was commissioned by the Irish antiquarian Lord Kingsborough, who later published Aglio’s transcription in his nine-volume work “Antiquities of Mexico” between 1831 and 1848. Aglio’s meticulous documentation provided a crucial record of the codex’s condition at the time, as it would later suffer significant damage over the years.

Wartime Devastation and Its Aftermath

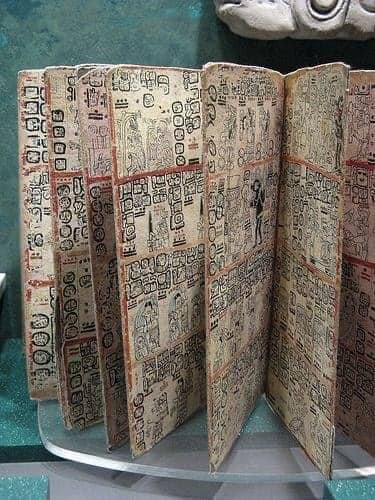

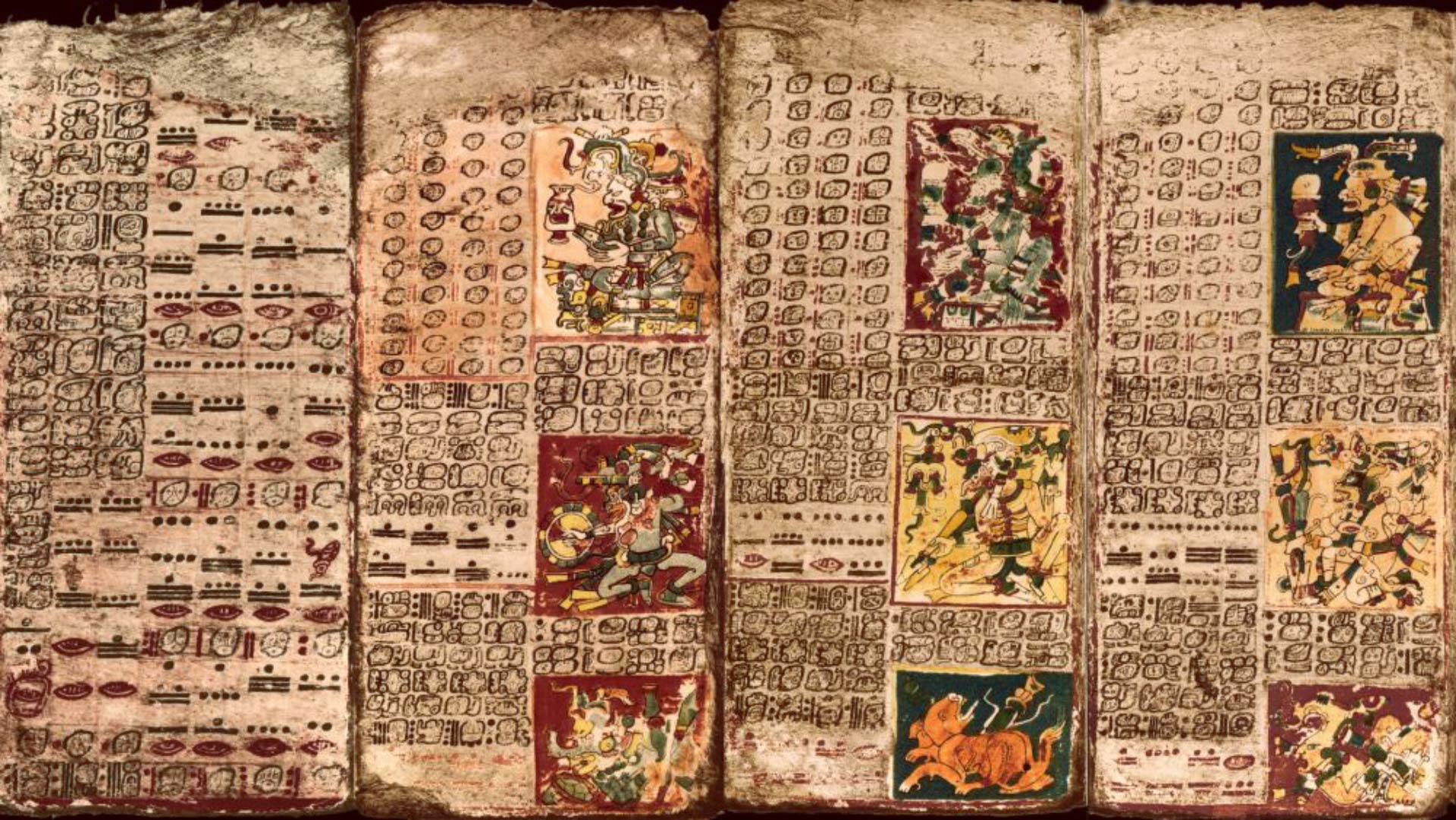

The Dresden Codex endured its most severe damage during World War II when it was stored in a flooded basement in Dresden, Germany during the bombing raids of February 1945. German historian G. Zimmerman noted that several pages, including 2, 4, 24, 28, 34, 38, 71, and 72, were particularly badly affected by the floodwaters. This water damage resulted in the loss of important details and degradation of the glyph images, which can be seen when comparing the current codex to Aglio’s transcriptions and the Förstemann facsimile editions from 1880 and 1892.

After the war, the task of restoring and preserving the codex became a priority. Historians and librarians worked to dry the damaged pages and return them to their protective glass cabinet, but this process led to further complications. The reordering of the pages during this time resulted in the reversal of several sheets, including 6/40, 7/39, and 8/38.

Challenges in Establishing the Correct Page Sequence

When Aglio first transcribed the Dresden Codex in 1825-1826, he divided the original manuscript into two parts, labeled Codex A and Codex B, and sequenced the pages by documenting the front side followed by the back side of each section. This organization, while systematic, did not accurately reflect the true reading order of the codex.

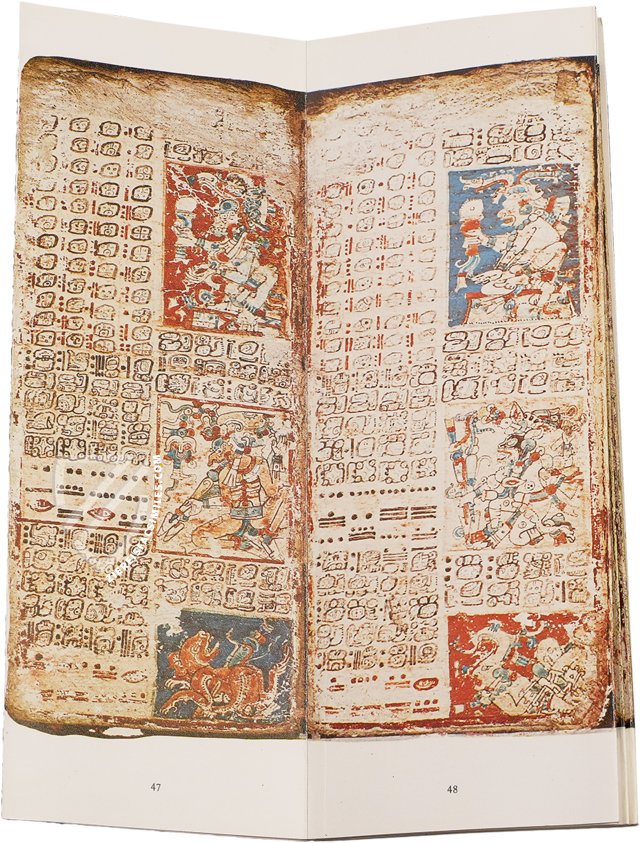

Modern historians, such as Helmut Deckert and Ferdinand Anders, have recognized that the correct reading order should traverse the complete front side of the manuscript followed by the complete back side, i.e., pages 1-24 followed by 46-74 and 25-45. This understanding conflicts with the two-part structure imposed by Aglio’s original page numbering.

Further complicating matters, in 1836, librarian K.C. Falkenstein made adjustments to the relative positioning of the pages “for esthetic reasons,” leading to the current two-part structure of similar length. Additionally, librarian E.W. Förstemann later noticed and corrected an error in Aglio’s page assignment for sheets 1/45 and 2/44.

Preserving a Vital Maya Manuscript

The Dresden Codex’s complex history of deterioration, transcription, and pagination highlights the challenges faced by scholars and custodians in preserving this invaluable pre-Columbian Maya manuscript. From Agostino Aglio’s pioneering documentation to the devastation of World War II and the subsequent efforts to restore and reorder the pages, the codex’s journey has been a testament to the resilience and dedication of those who have worked to safeguard this cultural treasure. As scholars continue to study and interpret the codex, the story of its preservation remains an integral part of its larger significance and legacy.