The Black Death, a catastrophic global epidemic of bubonic plague, left an indelible mark on Europe and Asia during the mid-1300s. Its arrival in Europe in October 1347, carried by 12 ships from the Black Sea, brought death and despair to the Sicilian port of Messina. The shocking sight of dead sailors and severely ill survivors covered in black boils oozing blood and pus greeted those who gathered at the docks. Despite hasty attempts by Sicilian authorities to expel the fleet of “death ships,” the Black Death would go on to claim over 20 million lives in Europe within the next five years, decimating nearly one-third of the continent’s population.

How Did the Black Plague Start?

Even prior to the arrival of the “death ships” in Messina, rumors had spread across Europe about a deadly plague sweeping through the trade routes of the Near and Far East. In the early 1340s, the disease had already struck various regions, including China, India, Persia, Syria, and Egypt. While the plague is believed to have originated in Asia over two millennia ago and likely spread through trading ships, recent research suggests that the pathogen responsible for the Black Death might have been present in Europe as early as 3000 B.C.

Symptoms of the Black Plague

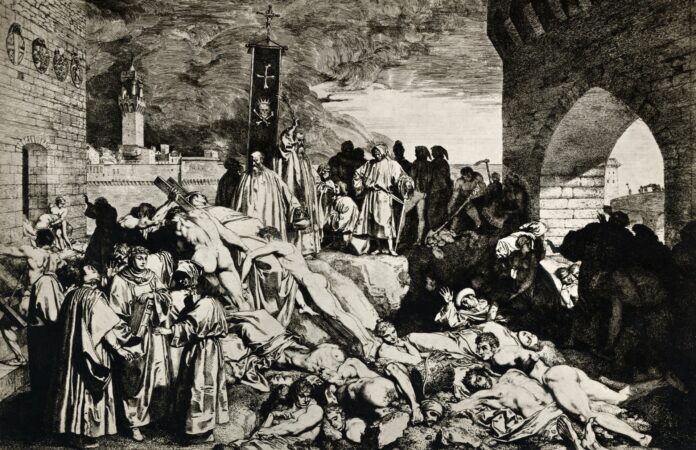

The European population was ill-prepared to confront the horrifying reality of the Black Death. Giovanni Boccaccio, an Italian poet, described the initial symptoms: swollen swellings, ranging from the size of an apple to an egg, appearing in the groin or under the armpits. These swellings, known as plague-boils, exuded blood and pus. Alongside these grotesque signs, victims experienced fever, chills, vomiting, diarrhea, excruciating pain, and, ultimately, death. The Bubonic Plague targeted the lymphatic system, causing swelling in the lymph nodes, and could spread to the blood or lungs if left untreated.

How Did the Black Death Spread?

The Black Death was a terrifyingly contagious disease, transmitted even through the mere touch of infected clothing. It also exhibited a swift and ruthless efficiency, capable of claiming lives overnight. Notably, the disease spread through the air, as well as through the bites of infected fleas and rats. These vectors thrived in medieval Europe, particularly on ships, which facilitated the rapid dissemination of the deadly plague from one port city to another. Consequently, after striking Messina, the Black Death reached Marseilles in France, Tunis in North Africa, and subsequently Rome, Florence, Paris, Bordeaux, Lyon, and London by the middle of 1348.

Understanding the Black Death

In modern times, scientists have identified the Black Death as a plague caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which is transmitted from person to person through the air and by infected fleas and rats. However, during the 14th century, there was no rational explanation for the epidemic. The modes of transmission remained unknown, and there were no known methods of prevention or treatment. Various theories circulated, including one proposing that the disease spread through the gaze of the sick. The lack of understanding fueled fear and panic among the populace.

How Do You Treat the Black Death?

Medieval physicians resorted to crude and unsanitary techniques such as bloodletting and boil-lancing, which were both dangerous and ineffective. Superstitious practices, such as burning aromatic herbs or bathing in rosewater or vinegar, were also common. In the midst of panic, healthy individuals took drastic measures to avoid the sick, with doctors refusing to treat patients, priests refusing to administer last rites, and shopkeepers closing stores. Even in rural areas, the disease persisted, affecting not only humans but also livestock, leading to a scarcity of wool in Europe. The desperation to survive sometimes led people to abandon their sick and dying loved ones, hoping to secure their own safety.

Black Plague: God’s Punishment?

Due to a lack of understanding about the disease’s biology, many believed the Black Death was a divine punishment, a consequence of sins committed against God. Greed, blasphemy, heresy, fornication, and worldliness were viewed as reasons for God’s wrath. Consequently, some communities sought to rid themselves of heretics and troublemakers as a means of appeasing God. Tragically, this resulted in the massacre of thousands of Jews in 1348 and 1349, while others sought refuge in less populous regions of Eastern Europe. The terror and uncertainty surrounding the epidemic drove some to lash out at their neighbors, while others turned inward, obsessing over the condition of their own souls.

Flagellants

In response to their powerlessness in the face ofthe Black Death, some individuals turned to extreme acts of religious devotion. The Flagellants, a movement that emerged during the plague, believed that self-inflicted pain and suffering would atone for their sins and appease God’s anger. They would march through towns and villages, whipping themselves with scourges, often tipped with metal spikes, while singing hymns and praying for salvation. The movement gained popularity but was condemned by the Church as heretical and disruptive to social order.

Social and Economic Impact

The Black Death had profound social and economic consequences. The massive loss of life resulted in labor shortages, leading to a collapse of feudalism and a shift in power dynamics. With a reduced workforce, peasants had more bargaining power and could demand higher wages and better working conditions. The scarcity of workers also prompted technological advancements and innovations to increase productivity. Additionally, the plague’s impact on the Church was significant, as the loss of faith and questioning of divine providence eroded the Church’s authority and contributed to the Reformation.

Aftermath and Later Outbreaks

After its initial devastating wave, the Black Death continued to resurface periodically, albeit with less severity. The second pandemic occurred in the late 14th century, and subsequent outbreaks followed in the 17th and 18th centuries. However, none of these subsequent waves matched the scale and devastation of the initial outbreak. By the 19th century, advances in medicine, sanitation, and public health measures significantly reduced the impact of the plague. Today, the bubonic plague can be effectively treated with antibiotics.

The Black Death was a transformative event in human history, leaving an indelible mark on Europe and Asia during the 14th century. The speed and severity of the epidemic, combined with the lack of understanding and effective treatments, led to widespread fear, panic, and social upheaval. The plague’s impact on population, labor, religion, and power structures shaped the trajectory of European history. While modern medicine has made significant strides in combating infectious diseases, the memory of the Black Death serves as a reminder of the devastating potential of pandemics and the importance of preparedness and scientific understanding in the face of such crises.