Imagine filing a complaint about poor customer service and having it preserved for 4,000 years. That’s exactly what happened with Nanni, a Babylonian trader who penned the world’s oldest known complaint letter. This clay tablet, discovered in the ancient city of Ur (modern-day Iraq), is more than just a fascinating artifact—it’s a window into the everyday frustrations of ancient Mesopotamian life and the early signs of globalization. At the center of this drama? Ea-nāṣir, a copper merchant whose shady business practices made him infamous.

The Discovery of the Complaint Letter

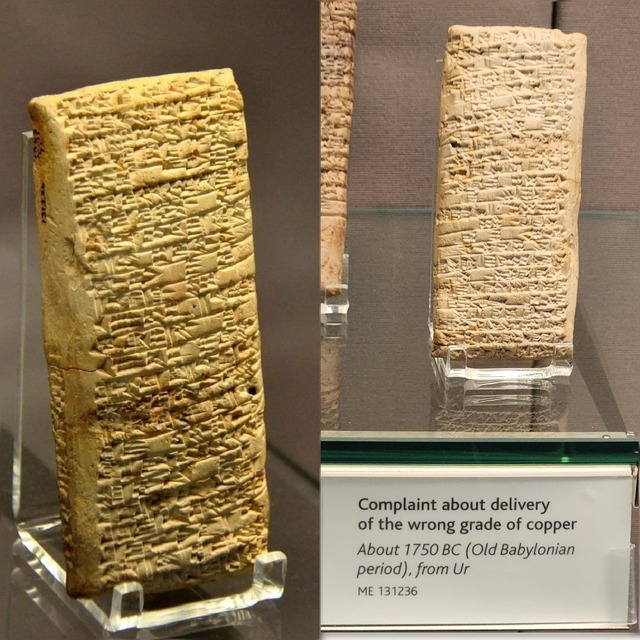

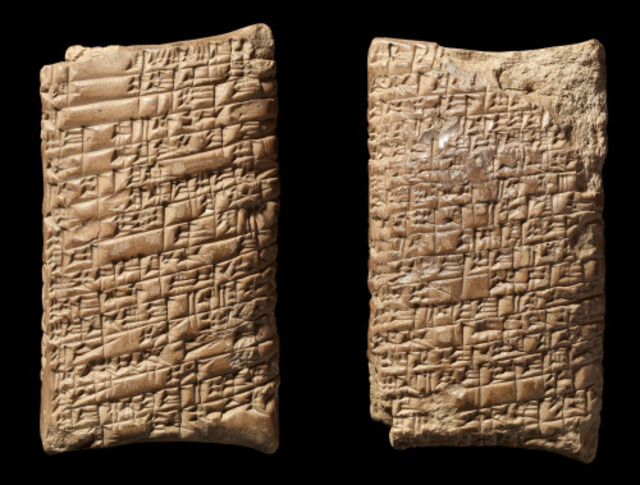

The tablet was unearthed nearly a century ago by the renowned archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley during excavations in Ur. It was found in what is believed to have been Ea-nāṣir’s residence, alongside other business records inscribed in cuneiform. Now housed in the British Museum, the palm-sized tablet is written in Akkadian, the lingua franca of ancient Mesopotamia. The letter not only reveals details of a botched business deal but also sheds light on the frustrations of a customer who felt deceived.

The Contents of the Complaint

The letter was dictated by Nanni, a trader who accused Ea-nāṣir of supplying low-quality copper ingots instead of the fine-quality material he had promised. Adding insult to injury, Ea-nāṣir reportedly dismissed Nanni’s messenger with a curt, “If you want to take them, take them. If you do not, go away!” Nanni was livid—not just about the inferior copper, but also the disrespect shown to his representative.

In his fiery letter, Nanni warned, “I will not accept any copper from you that is not fine quality,” and declared his intent to “inflict grief” on Ea-nāṣir for his perceived contempt. The vivid language of the complaint transcends time, giving us a glimpse of how business grievances were voiced in ancient times. It’s an age-old tale of unmet expectations and poor customer service.

Ea-nāṣir: A Notorious Merchant

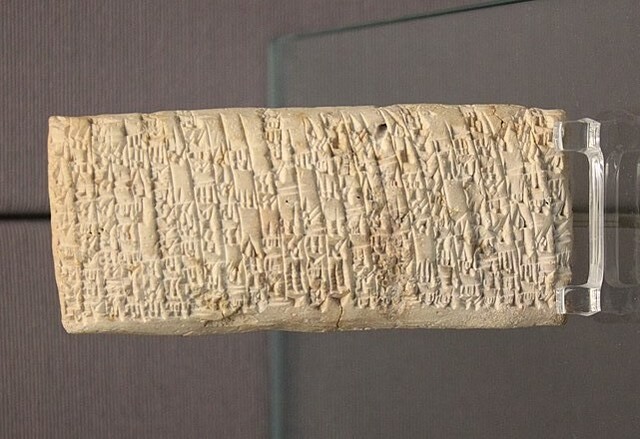

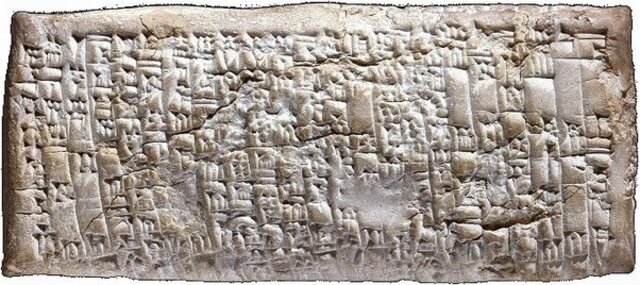

As it turns out, Nanni wasn’t the only one frustrated with Ea-nāṣir. Other clay tablets discovered at the site include similar complaints. One from a trader named Imgur-Sin admonishes Ea-nāṣir to “transfer good copper…so that I will not become upset!” Another letter from Nar-am implores him to “give very good copper” to avoid further dissatisfaction.

Ea-nāṣir’s reputation for shady dealings was evidently well-known in Ur. Yet, despite his questionable practices, his business seemed to thrive, suggesting that traders in the region may not have had many alternatives for sourcing copper. While Ea-nāṣir’s actions might seem unscrupulous by modern standards, they also highlight the challenges and limitations of trade in the ancient world.

The Bronze Age Economy and Globalization

Nanni’s complaint offers more than just a colorful anecdote; it’s a snapshot of the sophisticated economic system of Bronze Age Mesopotamia. Copper was a vital commodity, used to create tools, weapons, and vessels. However, the region around Ur lacked significant metal resources, forcing merchants to source copper from distant places like Dilmun, now known as Bahrain.

Trade was a collaborative effort, with merchants pooling resources—such as silver or sesame oil—to finance long, perilous journeys. Upon returning, the copper was sold, profits were divided, and tithes were paid to the palace and temples. This interconnected system underscores the complexities of early globalization. As Professor Lloyd Weeks of the University of New England notes, “People talk about globalization as a modern phenomenon, but the Bronze Age was arguably the first period where we see its effects on a large scale.”

Historical and Modern Parallels

What makes Nanni’s complaint so relatable today is its timeless subject matter. Who hasn’t felt the frustration of paying for a product or service that fails to meet expectations? In Nanni’s case, his grievances about poor-quality goods and disrespectful service could easily be echoed in modern online reviews or customer service complaints.

The letter has captured the imagination of modern audiences, spawning memes, comics, and even jokes comparing Ea-nāṣir to today’s unreliable vendors. It reminds us that while technology and economies have evolved, human frustrations over fairness and quality remain remarkably consistent.

Legacy of the Complaint Letter

The letter’s significance extends beyond its humor and relatability. For archaeologists, it’s a valuable artifact that illuminates the intricacies of Mesopotamian trade, the importance of copper, and the human dynamics that fueled these ancient economies. It’s also a testament to the power of written records, preserving a moment of indignation from a time long past.

Ea-nāṣir’s tale serves as a reminder of the enduring challenges of trade and the universal desire for accountability. It also highlights the role of merchants in shaping early economies and the delicate balance between reputation, trust, and survival in a competitive marketplace.

Conclusion

The 4,000-year-old complaint letter from Nanni to Ea-nāṣir is more than just an artifact; it’s a story that connects us to the ancient world in an unexpectedly relatable way. Through this small clay tablet, we gain insight into the complexities of Mesopotamian trade, the frustrations of early consumers, and the broader impact of globalization. In the end, the story of Ea-nāṣir and his copper debacle is not just a piece of history—it’s a reminder that some grievances truly are timeless.