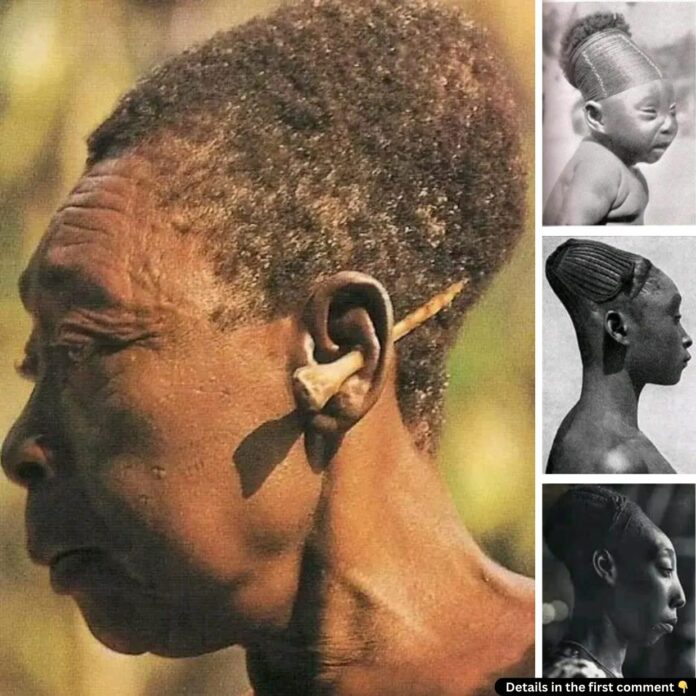

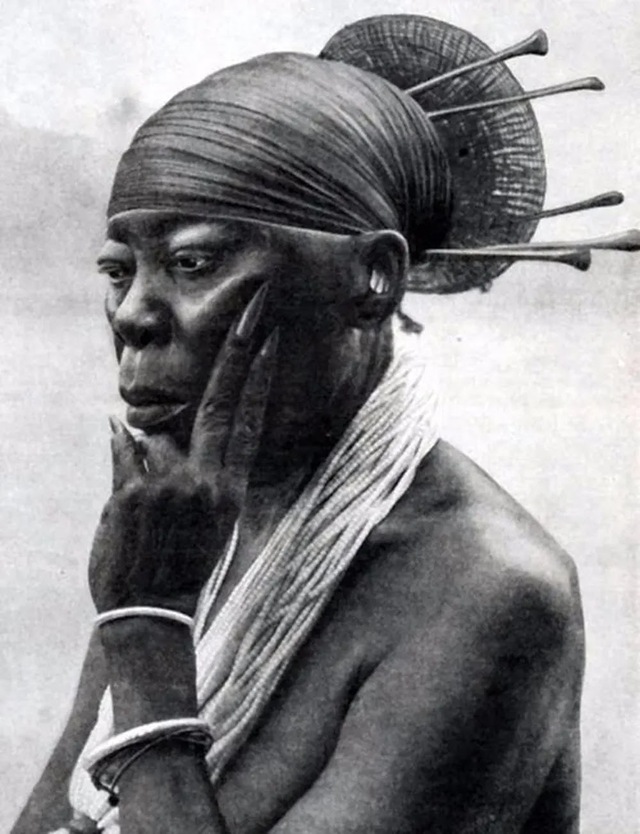

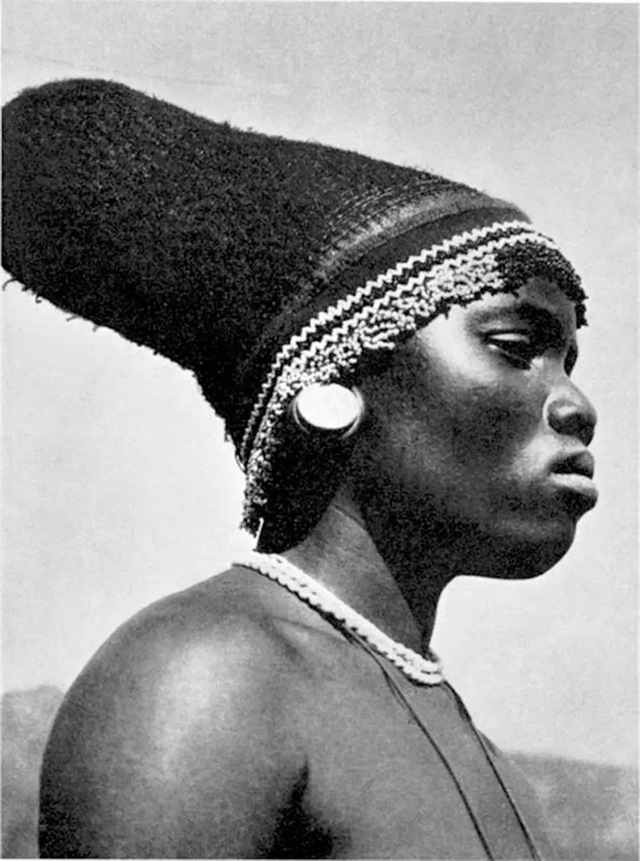

The Mangbetu people of Central Africa captivated early European explorers with their distinct cultural traditions and physical features. Among their most striking practices was the intentional elongation of the skull, a beauty standard that symbolizes intelligence, status, and power. Known as Lipombo, this custom has since faded due to colonial influence, yet it remains a fascinating chapter in human history, offering insights into the complex interplay between culture, aesthetics, and identity.

The Practice of Skull Elongation (Lipombo)

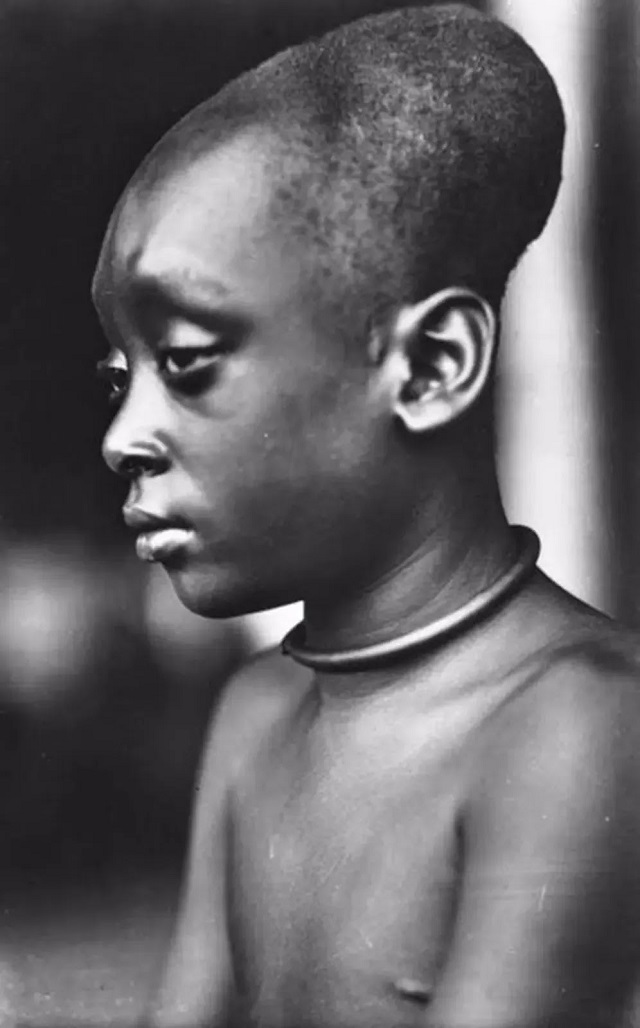

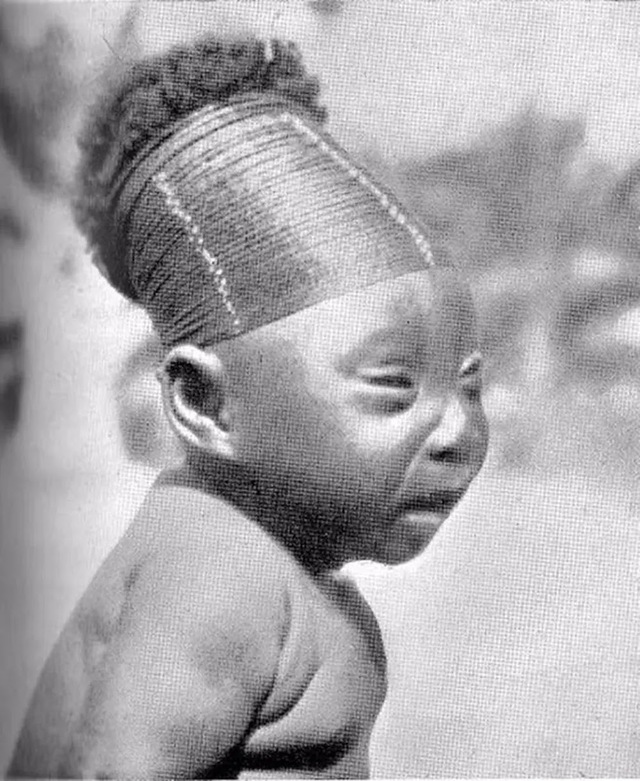

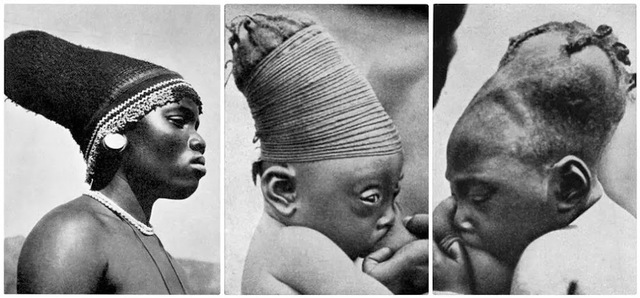

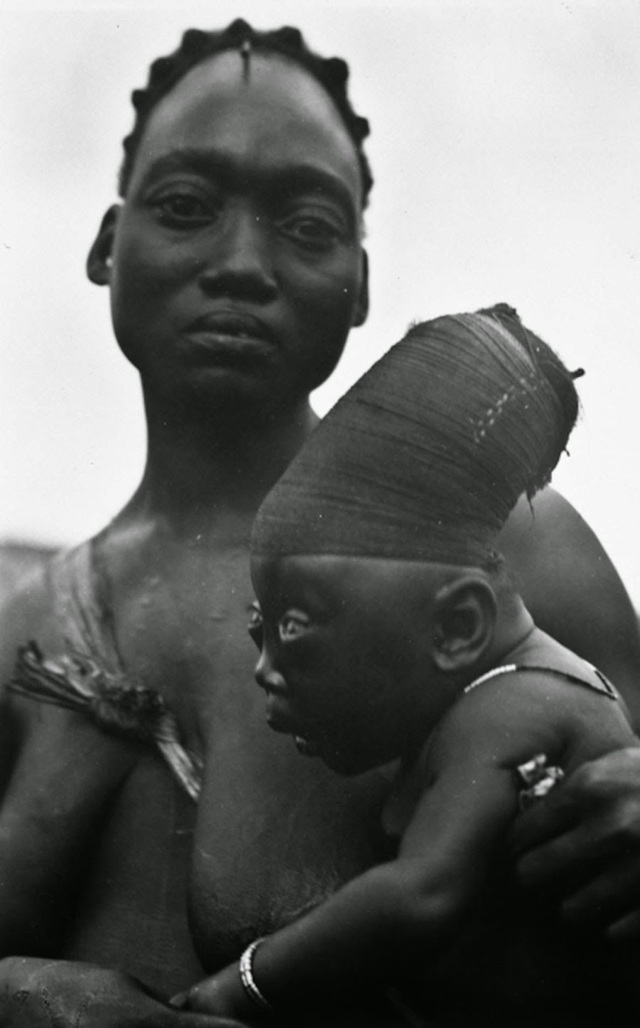

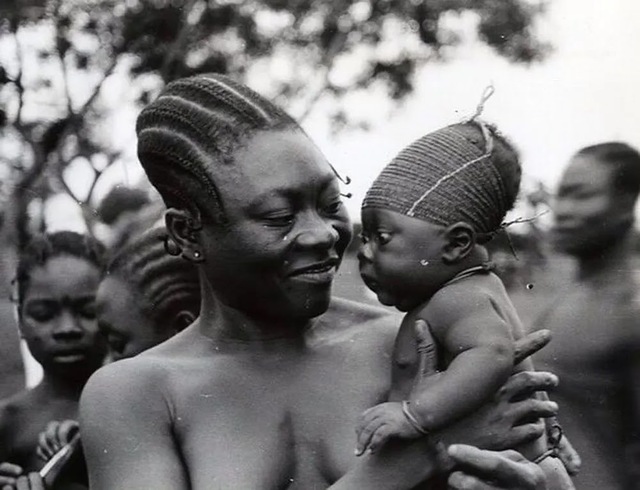

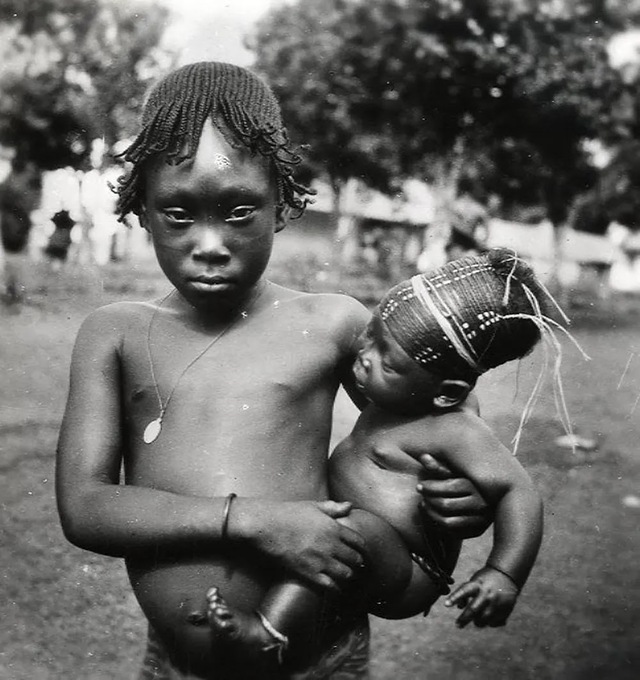

The Mangbetu’s tradition of skull elongation, called Lipombo, involved wrapping a baby’s head tightly with cloth while the cranial bones were still soft and malleable. This process began shortly after birth and continued for several years until the desired shape was achieved. The resulting elongated head became a defining characteristic of the Mangbetu aristocracy.

Deformation was often a gentle and gradual process, as parents adjusted the wrapping to ensure the shape developed harmoniously. While this may seem extreme to modern sensibilities, the practice was deeply rooted in Mangbetu culture and identity. It not only marked an individual’s social status but also reflected ideals of beauty and intelligence.

Video:

Cultural Significance of Lipombo

For the Mangbetu, an elongated head was far more than a physical trait—it was a symbol of majesty, power, and sophistication. The practice was primarily reserved for the ruling classes, serving as a visible marker of their elite status. It denoted wisdom and intelligence, qualities highly valued in leaders and decision-makers.

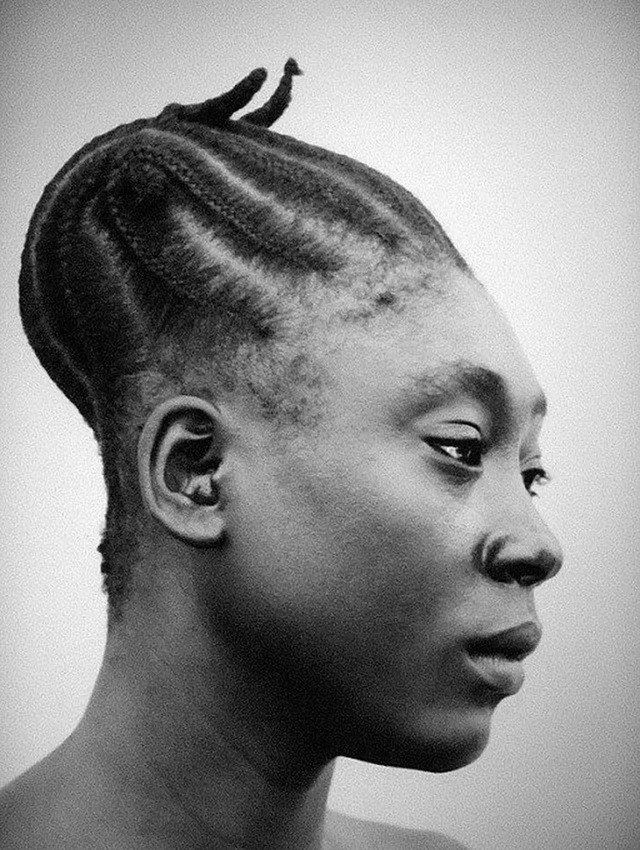

The elongated head was also an aesthetic ideal. Women often styled their hair in elaborate coiffures designed to accentuate the unique shape of their skulls. These hairstyles became an integral part of their cultural identity, further emphasizing the beauty and elegance associated with Lipombo.

Health and Biological Impact

While the idea of skull deformation may raise concerns about health implications, studies suggest that the practice likely had minimal impact on brain function. The human brain is remarkably adaptable and capable of growing within the confines of an elongated skull as long as intracranial pressure remains normal. There is no evidence to suggest that Lipombo caused cognitive impairment or physical harm beyond cosmetic changes.

This adaptability highlights the developmental plasticity of the human body and its ability to conform to cultural practices without compromising biological function. In the case of the Mangbetu, the practice was purely an aesthetic and symbolic choice, with no detrimental effects on the individual’s health.

The Decline of Lipombo

The decline of Lipombo began in the mid-20th century, with the increasing influence of European colonizers and the spread of Western values. The Belgian government, which ruled over colonial Congo, outlawed the practice, viewing it as primitive and incompatible with modern civilization. As Westernization took hold, traditional Mangbetu customs, including skull elongation, faded into obscurity.

Despite this, the legacy of Lipombo endures in the oral histories and cultural memory of the Mangbetu people. While the practice is no longer observed, it remains a source of pride and identity, symbolizing the creativity and resilience of their ancestors.

Daily Life and Social Structure of the Mangbetu

The Mangbetu people live in northeastern Congo, where they subsist through a combination of farming, fishing, hunting, and gathering. They are known for their sophisticated political systems and artistic achievements, which impressed early European travelers.

Marriage customs among the Mangbetu involve the exchange of bride-price, often including livestock. Polygynous marriages are widely accepted, and descent is patrilineal. These practices reflect the importance of family, community, and tradition in Mangbetu society.

The Mangbetu are also renowned for their skills as builders, potters, and sculptors. Their art often incorporates themes of power, beauty, and identity, making it a vital expression of their cultural values. While early explorers sensationalized certain aspects of their culture, such as supposed cannibalism, these misconceptions overshadow the sophistication and depth of Mangbetu traditions.

Global Context of Cranial Deformation

The Mangbetu were not the only culture to practice cranial modification. Historical records indicate that skull elongation has been observed in various societies across the globe. Hippocrates, the ancient Greek physician, described the Macrocephali (or Long-heads) in 400 BC, noting their custom of cranial deformation.

In Central and South America, the Maya and Inca also practiced skull elongation, associating it with nobility and divine status. These parallels suggest that the desire to modify the human body for cultural or symbolic purposes is a universal aspect of human history. While the methods and meanings varied, the underlying drive to express identity and status through physical appearance was a common thread.

Artistic and Aesthetic Expression

The Mangbetu’s emphasis on aesthetics extended beyond cranial modification to their hairstyles and art. Women adorned their elongated heads with intricate hairstyles that further emphasized the unique shape of their skulls. These coiffures were not only visually striking but also served as a celebration of cultural identity.

Mangbetu art, including pottery and sculpture, often reflected their ideals of beauty and power. Elongated forms were incorporated into their creations, showcasing their appreciation for symmetry and elegance. Today, these artifacts are valued not only for their artistic merit but also for their historical significance, offering a glimpse into the lives of the Mangbetu people.

Conclusion

The Mangbetu people’s tradition of skull elongation, Lipombo, represents a remarkable chapter in the history of human culture. This practice, which symbolized beauty, intelligence, and power, highlights the deep connection between physical appearance and social identity in Mangbetu society. While the custom has faded due to colonial influence and modernization, its legacy endures as a testament to the creativity and resilience of the Mangbetu people.

By examining practices like Lipombo, we gain a deeper appreciation for the diversity of human cultures and the ways in which societies have expressed their values through physical modification. The Mangbetu reminds us that beauty and identity are not fixed concepts but are shaped by the beliefs and traditions of each community. In preserving and studying their legacy, we honor the richness of human history and the ingenuity of our ancestors.