In the annals of history, few punishments can rival the sheer humiliation and torment inflicted upon those who fell victim to the dreaded “drunkard’s cloak.” While a hangover may seem like the worst consequence of overindulging, during the early modern era, heavy drinkers faced a far more severe and public reckoning for their transgressions. This article delves into the curious and cruel origins of this peculiar form of corporal punishment, exploring its prevalence across Europe and the lasting impact it had on those forced to endure its shameful spectacle.

The Drunkard’s Cloak: A Vessel of Shame

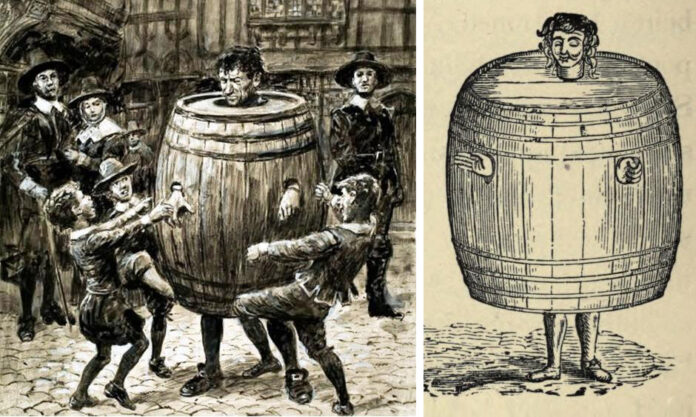

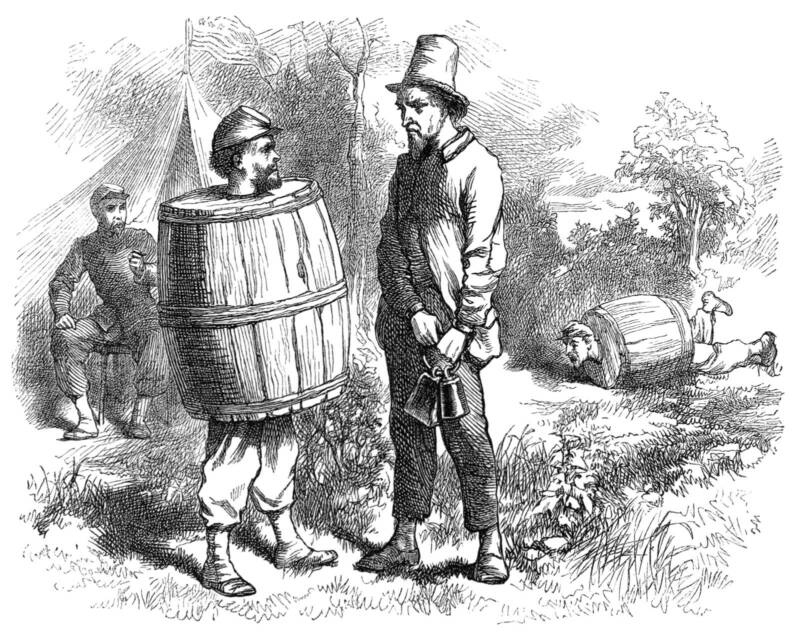

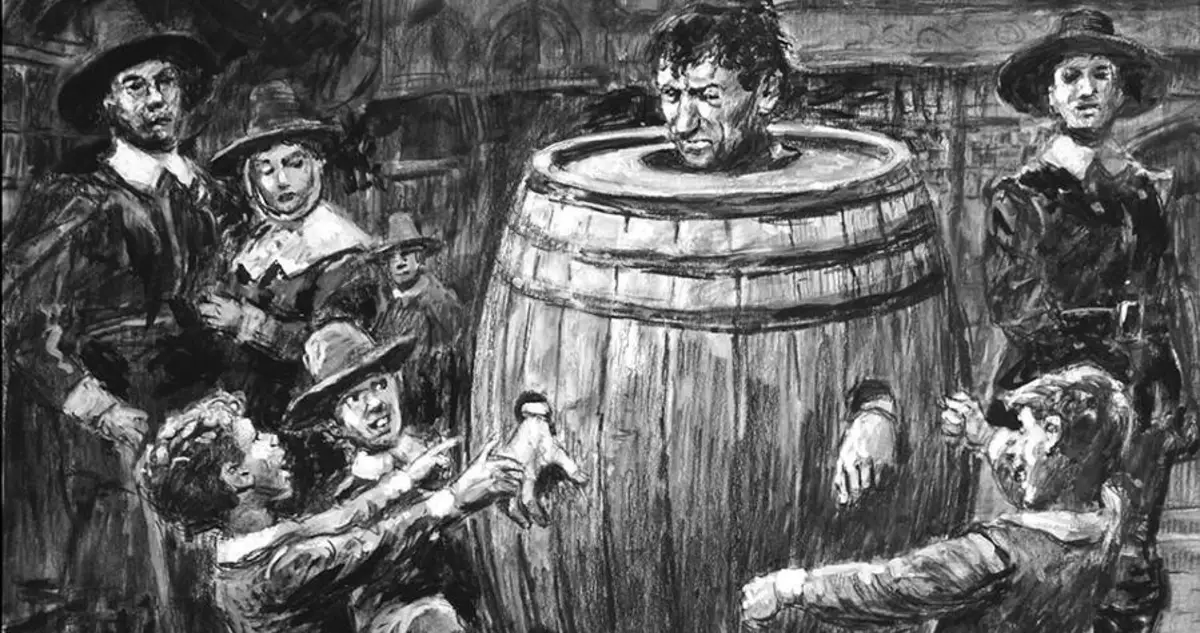

The drunkard’s cloak was a unique form of punishment that emerged during the early modern period, particularly in England and parts of Europe. This contraption consisted of an empty beer barrel, its top and sides cut to create openings for the head and arms of the offender. Once inside, the culprit would be paraded and pilloried around the streets, becoming an object of public ridicule and derision.

The objective behind this punishment was clear: to generate overwhelming shame and humiliation. By forcing the wrongdoer to don this garish and demeaning attire, the authorities aimed to send a powerful message to the community, demonstrating the social consequences of public drunkenness and disorderly conduct.

A Widespread Phenomenon

Several sources suggest that the drunkard’s cloak was a common form of punishment in medieval England, particularly after the passage of the Ale Houses Act of 1551, which sought to curb excessive drinking and the associated disorderly behavior. When the law failed to effectively control the problem, the drunkard’s cloak emerged as a popular corporal punishment for repeat offenders.

The use of this shaming device was not limited to England, however. Across Europe, the drunkard’s cloak was known by various names, including the “Schandmantel” in German and the “Spanish mantle” in Denmark. In the Netherlands, adulterous women were also subjected to this humiliating punishment in the 1640s in Delft, while Samuel Pepys reported a similar contraption in The Hague in 1660.

The Drunkard’s Cloak in Newcastle Upon Tyne

While the prevalence of the drunkard’s cloak in popular imagination may suggest a widespread use across England, the historical evidence points to a more localized phenomenon. According to historian Dan Jackson, the only archival evidence of the drunkard’s cloak in England dates back to the 1650s in Newcastle upon Tyne, where it was described in Ralph Gardiner’s “England’s Grievance Discovered.”

This regional focus highlights the importance of understanding the historical context and the nuances of local practices, rather than relying on generalized assumptions. The drunkard’s cloak may have been a source of fascination and horror in the public imagination, but its actual implementation appears to have been more geographically limited.

The Lasting Impact of Shame-Based Punishment

The use of the drunkard’s cloak and other shame-based approaches to address alcoholism and disorderly conduct reflects a broader trend in the past. Even today, the continued reliance on shame-based tactics to treat addiction underscores the persistent desire to publicly condemn and humiliate those perceived as deviating from societal norms.

However, research has shown that shame can often exacerbate addiction, as it triggers the very behaviors it aims to curb. This disconnect between historical practices and modern, evidence-based approaches highlights the need for a more nuanced and compassionate understanding of addiction and its treatment.

Conclusion

The drunkard’s cloak stands as a harrowing reminder of the lengths to which societies have gone to publicly shame and punish those deemed unfit. While the specifics of this unique punishment may have been confined to certain regions, its legacy serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of relying on shame-based approaches to address complex social issues.

As we reflect on the past, it is crucial that we learn from these historical examples and strive to develop more effective, evidence-based solutions that prioritize compassion and rehabilitation over public humiliation. Only then can we truly break the cycle of shame and address the root causes of addiction and disorderly behavior in a meaningful and lasting way.