In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, daring explorers ventured into the dense jungles of Mesoamerica and South America, uncovering ruins of ancient civilizations that had been hidden for centuries. Armed with little more than curiosity, maps, and the tools of their time, these adventurers documented their findings, bringing the rich histories of the Maya, Inca, and other cultures into the global spotlight. Their efforts not only illuminated the architectural and cultural achievements of these civilizations but also laid the foundation for modern archaeology.

Uncovering Mesoamerican and South American Ruins

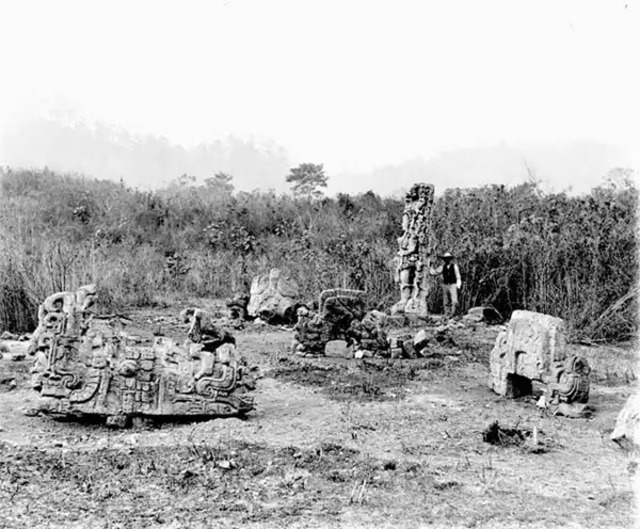

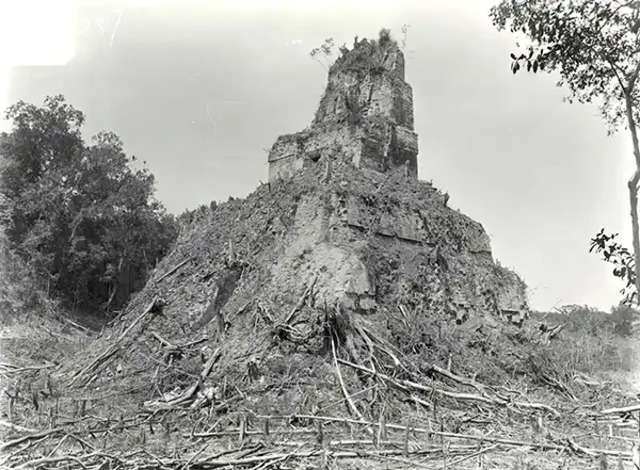

The jungles of Central and South America have long concealed ancient cities, swallowed by nature after the decline of the civilizations that built them. For centuries, these ruins were known only to the Indigenous peoples of the region, who preserved their memory through oral traditions. As word of these hidden wonders spread to Europe and North America in the 19th century, a wave of explorers set out to rediscover them.

Guided by local knowledge, these expeditions often began with tales of mysterious “lost cities” and monuments hidden beneath the foliage. Among the most celebrated discoveries were the Maya cities of Copán, Palenque, and Tikal, as well as the Inca citadel of Machu Picchu. These sites revealed advanced engineering, astronomical knowledge, and a rich artistic heritage, challenging prevailing assumptions about the capabilities of ancient peoples.

Video:

John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood: The Pioneers

One of the most iconic duos in early Mesoamerican exploration was John Lloyd Stephens, an American diplomat, and Frederick Catherwood, a British artist. In 1839, Stephens was appointed U.S. Ambassador to Central America, a role that allowed him to travel extensively. Accompanied by Catherwood, he documented Maya ruins in what is now Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico.

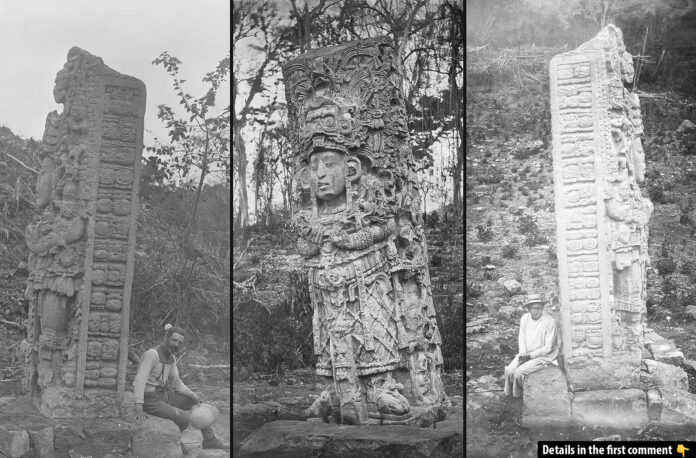

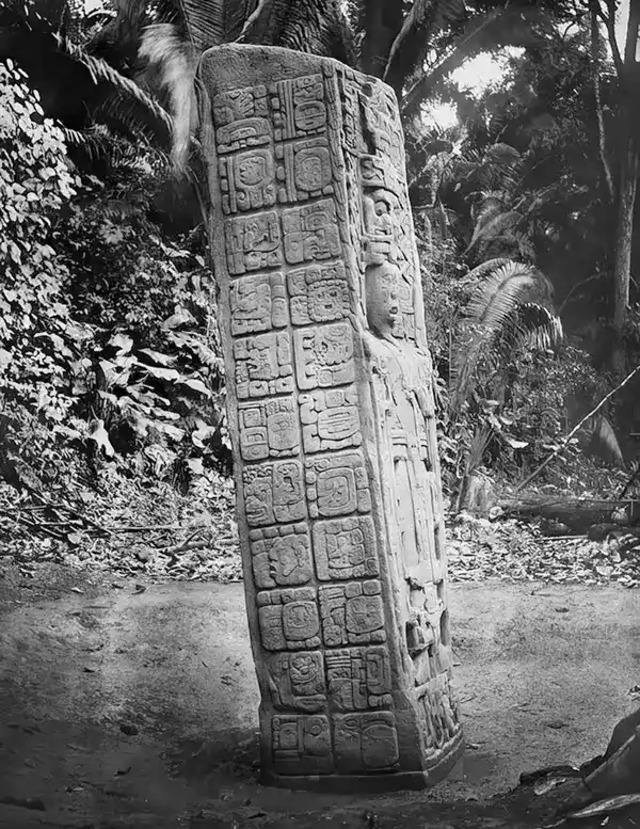

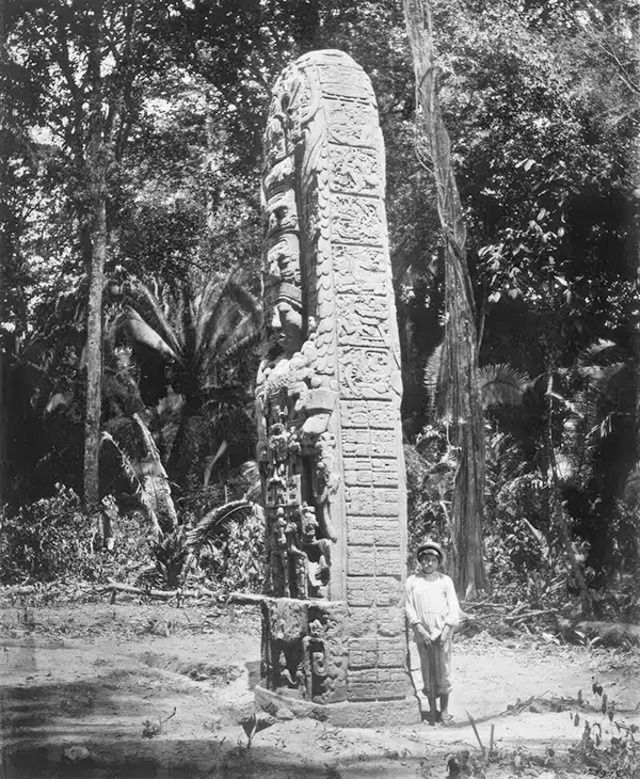

At Copán, Stephens was struck by the intricacy of the carved stelae and altars, describing them as “works of art” that proved the sophistication of the Maya. Catherwood’s detailed illustrations captured the grandeur of these monuments, even as they were overgrown with vines and hidden in dense jungle. Their collaborative book, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatán, captivated audiences and inspired a new wave of explorers.

Alfred Maudslay’s Contributions to Maya Archaeology

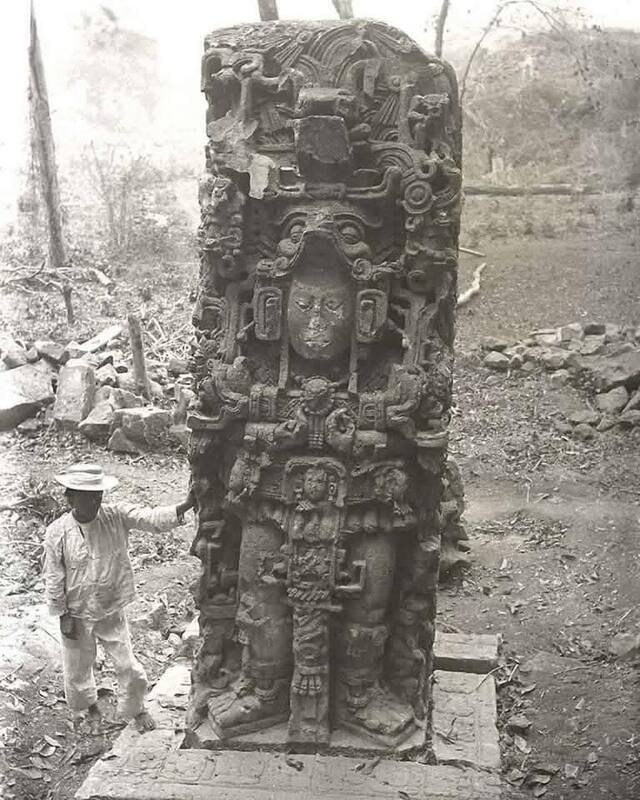

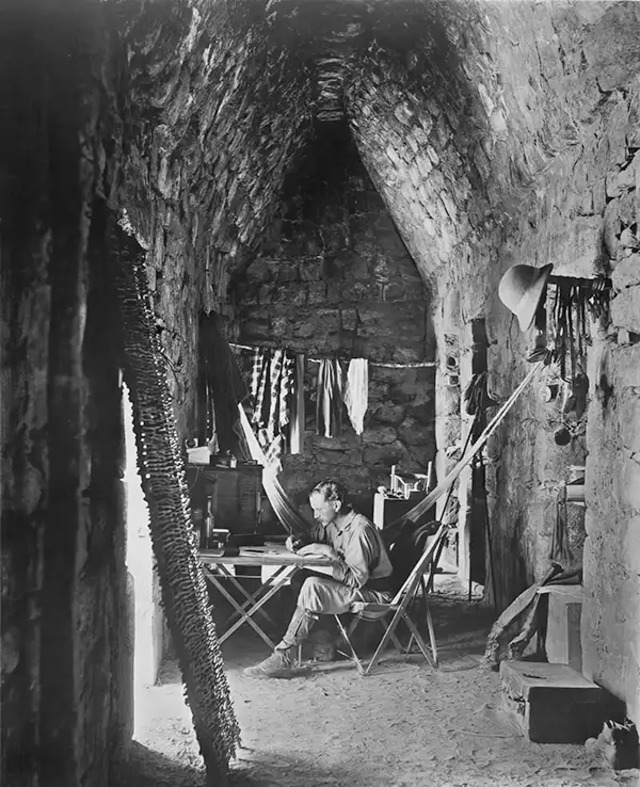

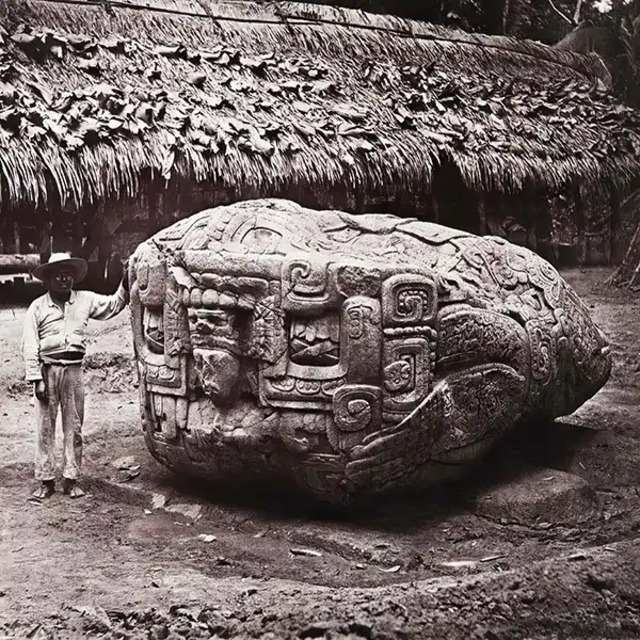

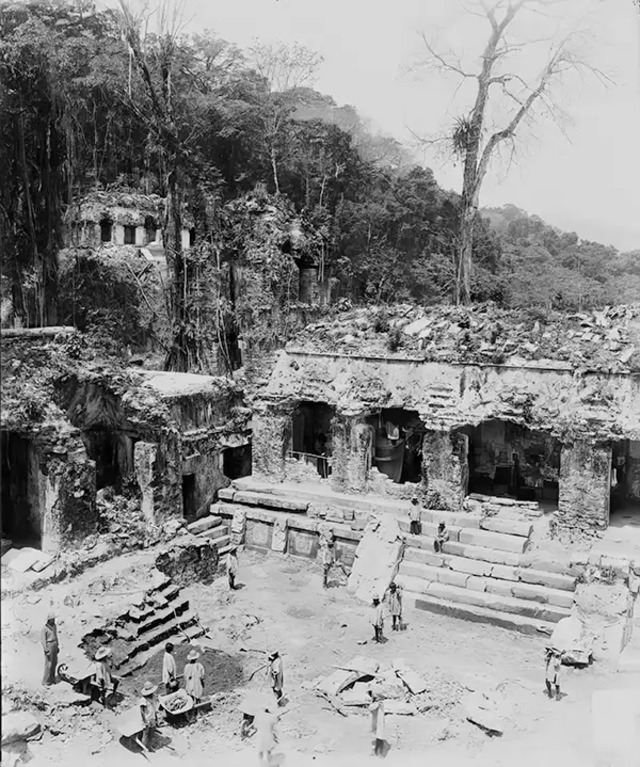

Alfred Percival Maudslay, a British archaeologist, played a pivotal role in the late 19th century by combining exploration with meticulous documentation. Using the emerging technology of dry plate photography, Maudslay created some of the earliest photographic records of Maya sites. His work at Copán, Quiriguá, and Chichén Itzá set new standards for archaeological fieldwork.

Maudslay’s innovations extended beyond photography. He employed Italian technicians to make plaster and papier-mâché casts of carvings, ensuring that detailed impressions could be studied even after the originals had deteriorated. His efforts to record hieroglyphs and architectural details provided a foundation for deciphering Maya script and understanding the cultural significance of these sites.

Hiram Bingham and the Rediscovery of Machu Picchu

In 1911, Hiram Bingham, an American historian, embarked on a journey to uncover the lost city of the Incas. Guided by local villager Melchor Arteaga, Bingham was led to Machu Picchu, a sprawling Inca citadel perched high in the Andes. Though locals had long known of the site, Bingham’s detailed documentation brought it to international attention.

Bingham’s subsequent excavations revealed the architectural brilliance of the Incas, including the Temple of the Sun and the Intihuatana stone, believed to have been used for astronomical observations. However, his role in the “discovery” of Machu Picchu remains controversial, as earlier visitors like Agustín Lizárraga had already noted the site’s existence.

Key Sites Explored During the Expeditions

Copán:

Located in present-day Honduras, Copán is renowned for its stelae, altars, and the Hieroglyphic Stairway, which contains the longest known Maya text. The site was a focal point for both Stephens and Maudslay, who marveled at its artistic and historical significance.

Quiriguá:

This Guatemalan site is home to some of the tallest Maya stelae ever discovered, including Stela D, which depicts the ruler K’ak’ Tiliw Chan Yopaat. Maudslay’s detailed photographs and casts captured the grandeur of these monuments.

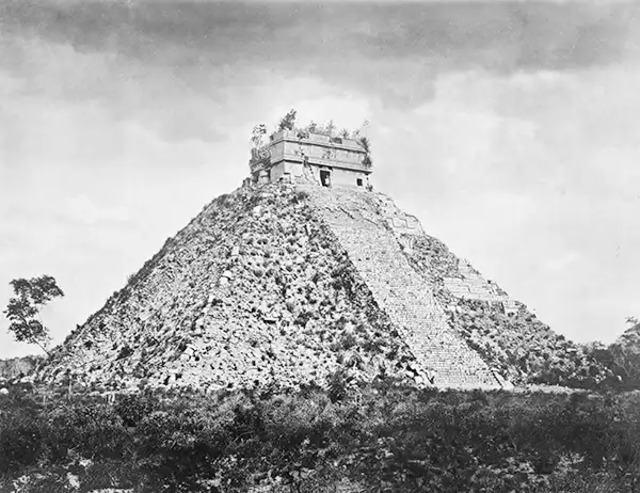

Chichén Itzá:

In Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, the Temple of Kukulcan and the Great Ball Court were among the highlights of Maudslay’s work. His pioneering use of photography preserved images of these structures as they were being excavated.

Machu Picchu:

The crowning achievement of Inca architecture, Machu Picchu’s terraced slopes, temples, and stone walls remain an enduring symbol of Inca ingenuity. Bingham’s documentation of the site remains one of the most influential archaeological efforts of the 20th century.

The Role of Indigenous Knowledge and Local Guides

The success of these expeditions owed much to the knowledge and assistance of Indigenous guides. Figures like Gorgonio López, who guided Maudslay through Central America, and Melchor Arteaga, who led Bingham to Machu Picchu, were instrumental in navigating dense jungles and identifying sites of interest. Their contributions highlight the importance of collaboration between explorers and local communities.

Artistic and Photographic Documentation

Illustrations by Frederick Catherwood and photographs by Alfred Maudslay and others played a crucial role in preserving the visual history of these sites. Catherwood’s detailed drawings brought Maya art to life for 19th-century audiences, while Maudslay’s photographs offered an unprecedented level of accuracy. These records remain invaluable for studying how the sites have changed over time.

Challenges of the Era

Exploring Mesoamerica and South America in the 19th and early 20th centuries was fraught with challenges. Dense jungles, extreme weather, and limited technology made documentation and preservation difficult. Many artifacts were lost to looters or deteriorated due to exposure. Additionally, early explorers often misunderstood the cultures they studied, framing their achievements through a Eurocentric lens.

The Legacy of Historical Expeditions

The expeditions of Stephens, Catherwood, Maudslay, and Bingham laid the groundwork for modern archaeology. Their meticulous documentation and efforts to preserve ancient sites have provided invaluable insights into the civilizations of Mesoamerica and South America. However, their work also raises ethical questions about the removal of artifacts and the representation of Indigenous histories.

Conclusion

The rediscovery of ancient civilizations in Mesoamerica and South America is a testament to the perseverance and curiosity of 19th and 20th-century explorers. Through their work, the world gained a deeper appreciation for the artistic, architectural, and cultural achievements of the Maya, Inca, and other peoples. As we continue to study these sites, their legacy reminds us of the importance of preserving and respecting the history of all cultures.