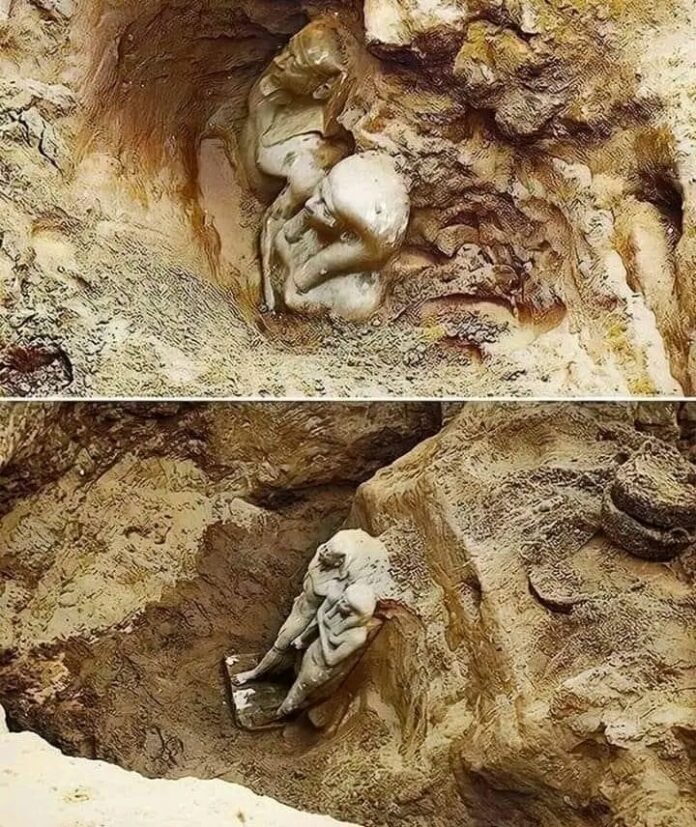

On January 10, 1910, a remarkable discovery was made on the Giza plateau in Egypt. Excavators under the direction of George Reisner, head of the joint Harvard University-Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Expedition to Egypt, uncovered an astonishing collection of statuary in the Valley Temple connected to the Pyramid of Menkaure. This finding would shed light on the serene ethereal beauty, raw royal power, and artistic virtuosity that were seamlessly captured in a breathtaking, nearly life-size statue of the pharaoh Menkaure and a queen.

The Menkaure Complex

Pyramids were not stand-alone structures in ancient Egypt. The pyramids at Giza formed part of a much larger complex that included a temple at the base of the pyramid, long causeways and corridors, small subsidiary pyramids, and a second temple (known as a valley temple) some distance from the pyramid. These Valley Temples were used to perpetuate the cult of the deceased king and were active places of worship for hundreds of years after the king’s death. Images of the king were placed in these temples to serve as a focus for worship, including the magnificent seated statue of Khafre, now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

The Astonishing Cache of Statuary

In the southwest corner of the Menkaure Valley Temple, Reisner’s team discovered a magnificent cache of statuary carved in a smooth-grained dark stone called greywacke or schist. Among the find were a number of triad statues, each showing three figures: the king, the goddess Hathor, and the personification of a geographic region. Hathor was a prominent figure in the pyramid temple complexes, worshipped alongside the supreme sun god Re and the god Horus, who was represented by the living king. Her connection to the wife of the living king and the mother of the future king made her a fierce protector of the royal lineage.

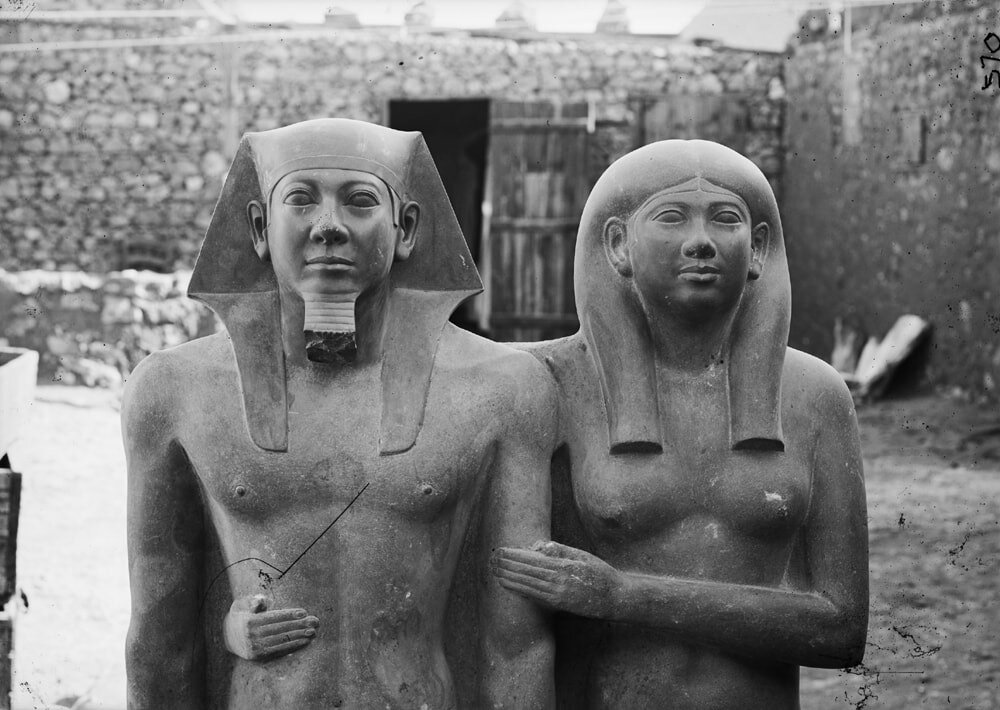

In addition to the triads, the excavation revealed the extraordinary dyad statue of Menkaure and a queen, a breathtakingly singular work of art. The two figures stand side-by-side, Menkaure’s head noticeably turned, as if emerging from an architectural niche. The king’s youthful, broad-shouldered body is adorned with the traditional pharaonic insignia, while his queen provides the perfect female counterpart, her sensuously modeled, beautifully proportioned body accentuated by a clinging garment.

The Artistry and Significance

What sets this statue apart is the remarkable individualization of the features of both the king and the queen, a departure from the purely idealized manner typical of royal images. Through the overlay of royal formality, we see the depiction of living, breathing individuals filling the roles of pharaoh and queen.

The dyad was never fully finished, with the area around the lower legs lacking a final polish and no inscription present. However, the presence of bright paint atop the smooth, dark greywacke suggests an intriguing possibility – that the paint may have been intended to wear away over time, revealing the immortal, black-fleshed “Osiris” Menkaure beneath.

The unusual absence of the protective cobra (known as a uraeus) on the king’s brow has led to the suggestion that both the king’s nemes and the queen’s wig were originally covered in precious metal, with the cobra as part of that addition.

Conclusion

The discovery of the Menkaure and queen dyad statue in 1910 was a remarkable moment in the annals of Egyptology. This breathtaking work of art, with its serene ethereal beauty, raw royal power, and evidence of artistic virtuosity, continues to captivate and inspire scholars and enthusiasts alike. The insights it provides into the ancient Egyptian conception of kingship, the role of the queen, and the enduring legacy of Menkaure and his dynasty are invaluable. This masterpiece stands as a testament to the enduring brilliance of the ancient Egyptian civilization.