Nestled in eastern Utah, Ninemile Canyon is a treasure trove of ancient art and history, earning its nickname as “the world’s longest art gallery.” This 40-mile stretch of rugged canyon is home to thousands of petroglyphs and pictographs, many over a thousand years old, created by the Fremont culture and later enriched by the Ute people. Beyond its artistic significance, the canyon holds a wealth of archaeological and historical importance, making it a must-visit destination for history enthusiasts and nature lovers alike.

Geography and Natural Features

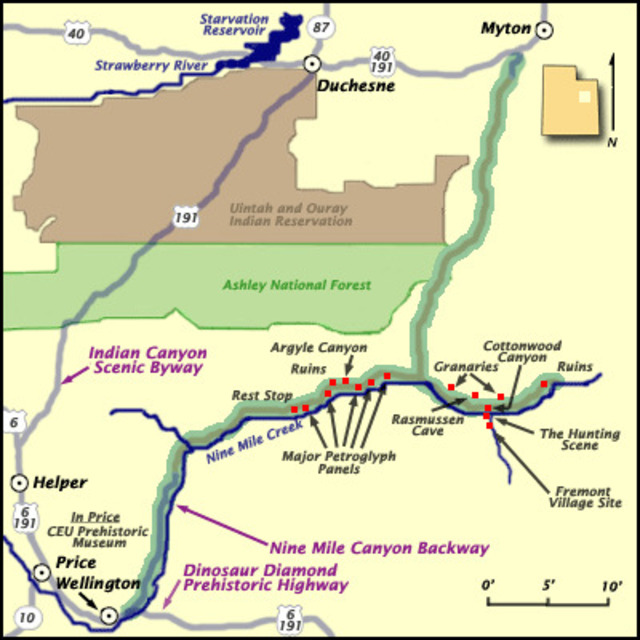

Ninemile Canyon meanders through the landscape of Carbon and Duchesne counties, cutting a dramatic path through Utah’s rugged terrain. Its winding route, dotted with tributary canyons like Argyle and Cottonwood, reflects the power of Nine Mile Creek—a year-round water source crucial to the area’s inhabitants, past and present.

Unlike many arid regions, Nine Mile Creek’s steady flow supported both the Fremont people and later settlers. It nourished crops, sustained wildlife, and carved the canyon’s intricate formations. This geographical lifeline not only shaped the landscape but also played a pivotal role in attracting human settlement and cultural expression.

Video:

The Fremont Culture: Art and Innovation

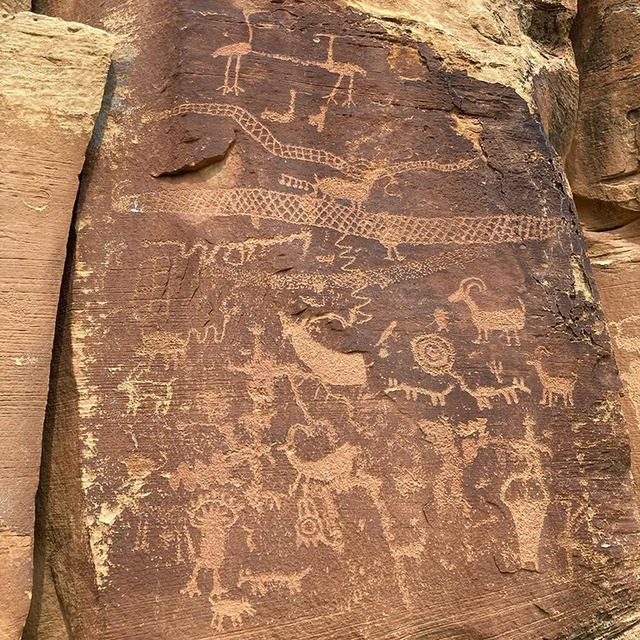

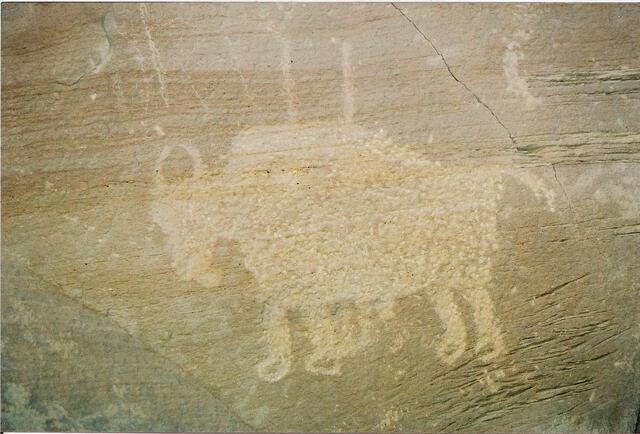

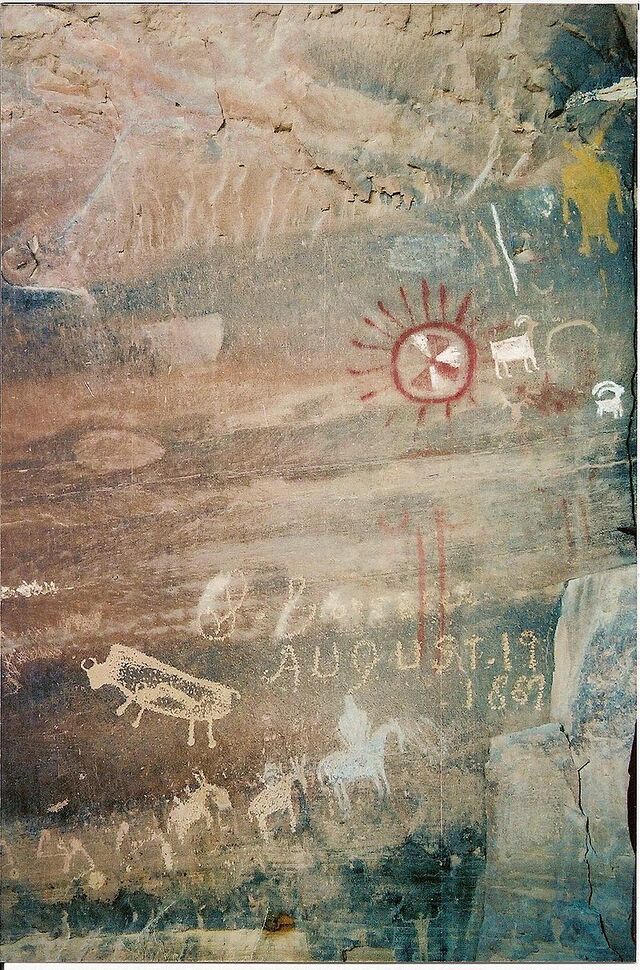

The Fremont people, who occupied Ninemile Canyon between AD 950 and 1250, left an indelible mark on the area. Their artistry is evident in the thousands of petroglyphs and pictographs adorning the canyon walls. These images depict everything from bighorn sheep and human figures to abstract symbols, offering a glimpse into their beliefs, daily life, and interactions with nature.

Unlike purely hunter-gatherer societies, the Fremont cultivated corn and squash, using irrigation systems that harnessed the creek’s water. Their ingenuity extended to architecture, as evidenced by pit houses, rock shelters, and granaries perched on cliff ledges. These structures reflect a blend of practicality and resilience, showcasing their ability to adapt to the canyon’s challenges.

The Ute People: Adding Layers to the Story

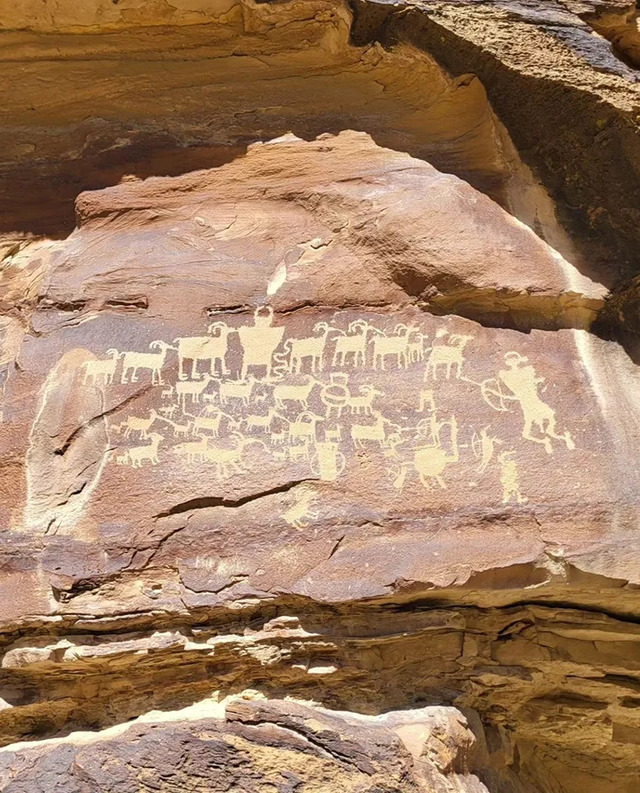

By the 16th century, the Ute people had made their way into Ninemile Canyon, adding their own artistic flair to the existing Fremont works. Ute petroglyphs often depict scenes of hunters on horseback, a stark contrast to the Fremont’s agricultural themes. These images, some dating to the 1800s, highlight the Ute’s deep connection to the land and their evolving way of life.

Interestingly, while Ute artifacts abound in the canyon, there is little evidence of permanent settlements. This suggests that the Ute used Ninemile primarily as a hunting and travel corridor, leaving behind art that documents their presence and interactions with the environment.

Archaeological Discoveries: Unearthing the Past

Archaeologists have identified more than 1,000 rock art sites in Ninemile Canyon, with over 10,000 individual images cataloged. Among the most famous is the Cottonwood Panel, also known as “The Great Hunt,” which vividly portrays a communal hunting scene. This masterpiece, along with others, underscores the canyon’s reputation as a hub of prehistoric creativity.

In addition to rock art, the canyon boasts remnants of Fremont architecture and artifacts, including pottery, tools, and irrigation systems. While much of the canyon remains unexcavated, these discoveries provide valuable insights into the lives of its ancient inhabitants.

The Canyon’s Historical Role

Ninemile Canyon’s significance extends beyond its prehistoric roots. In the 19th century, it became a vital transportation route, connecting Fort Duchesne to the railroad in Price. The road, built by the Buffalo Soldiers of the 9th Cavalry Regiment in 1886, facilitated the movement of goods, mail, and people, transforming the canyon into a bustling corridor.

During this time, settlers established ranches and a small community known as Harper. Although the town thrived briefly, it was abandoned by the early 20th century, leaving behind a legacy of resilience and adaptation that mirrors the canyon’s ancient inhabitants.

Preservation and Modern Challenges

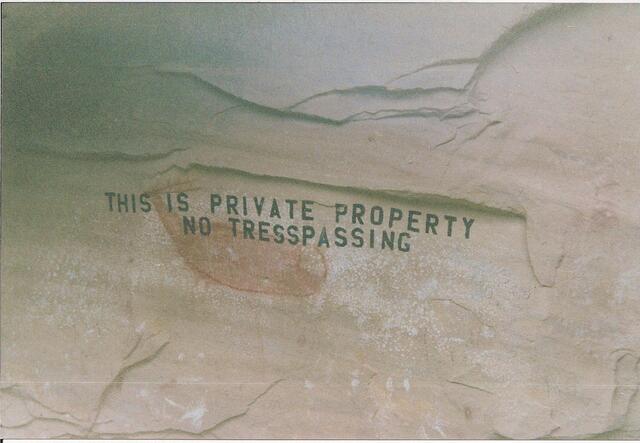

While Ninemile Canyon remains a testament to human creativity and resourcefulness, it faces significant challenges in the modern era. Industrial activities, particularly natural gas development, have brought increased truck traffic and dust, threatening the preservation of its fragile rock art. Dust clouds not only obscure the petroglyphs but also accelerate their erosion, prompting concerns among conservationists.

Efforts to mitigate these impacts include road paving projects and the application of dust-control measures. However, balancing economic development with cultural preservation remains a delicate task. Conservation groups and local authorities continue to advocate for sustainable practices that protect the canyon’s invaluable heritage.

Conclusion: Preserving a Timeless Legacy

Ninemile Canyon is more than just a collection of rock art—it’s a living archive of human history and creativity. From the ingenuity of the Fremont to the adaptability of the Ute and the resilience of early settlers, the canyon tells a story of survival, innovation, and cultural expression.

As we navigate the challenges of preservation in a modern world, Ninemile Canyon reminds us of the importance of safeguarding our shared heritage. By protecting this unique “art gallery,” we honor the legacy of its creators and ensure that future generations can marvel at its wonders. Ninemile Canyon is not just a window into the past; it is a bridge connecting us to the enduring spirit of human creativity and resilience.