The Sutton Hoo burial site in Suffolk, England, stands as a remarkable window into Anglo-Saxon history, long linked to royal figures like King Rædwald of East Anglia. Adorned with treasures such as the famed helmet, it has symbolized regal splendor. However, new research by Dr. Helen Gittos of Oxford suggests these graves may belong to Anglo-Saxon warriors who served the Byzantine Empire, revealing fascinating ties between early medieval England and the Eastern Mediterranean.

The Importance of Sutton Hoo

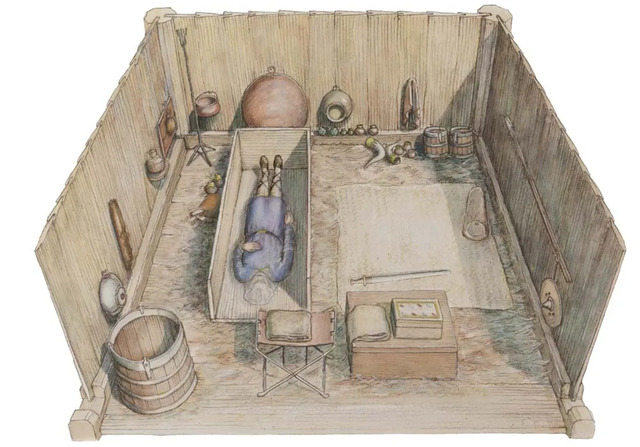

Sutton Hoo, discovered in 1939, comprises 20 burial mounds, including the famous ship burial under Mound 1. The 27-meter oak ship, laden with treasures, provided unprecedented insights into Anglo-Saxon society. Among the burial goods were weapons, ornate jewelry, silverware, and textiles, all of which indicated the high status of the individuals interred. These findings led historians to conclude that the burial site belonged to the Anglo-Saxon elite, likely King Rædwald, who ruled in the early 7th century.

The Sutton Hoo helmet, one of the most iconic finds, became a symbol of Anglo-Saxon craftsmanship and culture. Decorated with images of mounted warriors, the helmet has long been viewed as a testament to the martial prowess and artistic sophistication of this period. Yet, Dr. Gittos’s research reveals an entirely new dimension to these artifacts, suggesting they may have ties to the Byzantine world.

Watch the excavation of the Sutton Hoo ship burial – uncover the secrets of this ancient Anglo-Saxon site and explore the extraordinary artifacts uncovered during this historic dig!

Byzantine Connections in Sutton Hoo

Dr. Gittos highlights several artifacts from Sutton Hoo that suggest links with the Byzantine Empire. Among these are silver spoons inscribed with Greek text, a silver platter bearing the monogram of Emperor Anastasius I (491–518 CE), and a bronze bowl from the Eastern Mediterranean. While such items were previously thought to indicate trade, Gittos proposes a more personal connection: these were the belongings of Anglo-Saxon warriors who served in the Byzantine military and brought these treasures home.

The Byzantine Empire, engaged in fierce conflicts with the Sasanian Empire during the 6th century, actively recruited skilled mercenaries from across Europe. These warriors, known as foederati, included Britons renowned for their woodland combat skills. The prestige of serving in the Byzantine military and the rewards of such campaigns likely elevated the social status of returning warriors, allowing them to receive elaborate burials like those at Sutton Hoo.

Anglo-Saxon Mercenaries in Byzantine Service

The Byzantine Empire’s recruitment efforts extended across Europe, with mercenaries enticed by promises of gold and the prestige of serving in the emperor’s army. Historical records, including the Strategikon by Emperor Maurice, detail the military prowess of foreign recruits, particularly their cavalry skills. Anglo-Saxon warriors, noted for their equestrian expertise, would have been valuable assets to the Byzantine military.

These mercenaries were often equipped with Byzantine armor and weapons, which they could later modify or replicate upon returning home. The Sutton Hoo helmet and chain mail coat bear distinct Roman and Byzantine influences, further supporting the theory that the individuals buried at Sutton Hoo may have fought in the Byzantine army. The helmet’s articulated cheek and neck guards, features common in Roman designs, suggest a blending of Byzantine and Anglo-Saxon styles.

Video

Explore the treasures of Sutton Hoo, an Anglo-Saxon burial site that collected artifacts from across Europe and Asia – watch the video to uncover the rich history and cultural significance of this remarkable discovery!

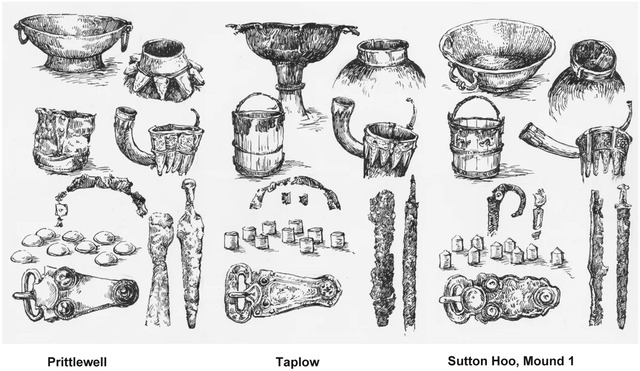

Insights from the Prittlewell Prince

The Prittlewell Prince, discovered in Essex in 2003, provides additional evidence of Anglo-Saxon connections to the Byzantine world. This unlooted grave contained items such as a bronze pitcher, silver spoons, and a hanging bowl, all of which were made in the Eastern Mediterranean. These artifacts, like those at Sutton Hoo, appear to have been brought back by a returning warrior rather than acquired through trade.

The parallels between Sutton Hoo and the Prittlewell grave underscore the broader cultural exchanges between Anglo-Saxon England and the Byzantine Empire. Such findings challenge the notion of early medieval England as isolated and instead highlight its role in a complex network of military and cultural interactions.

Rethinking the Sutton Hoo Narrative

Dr. Gittos’s research invites a reevaluation of Sutton Hoo’s historical significance. While the burial site has traditionally been associated with kings and local aristocrats, the presence of Byzantine artifacts and equestrian equipment suggests a different identity for those interred. Rather than solely royal figures, the individuals buried at Sutton Hoo may have been elite warriors whose status was elevated by their service in the Byzantine military.

This perspective reshapes our understanding of Anglo-Saxon society, emphasizing the dynamic interplay between local traditions and broader cultural influences. The lavish burials at Sutton Hoo reflect not only wealth and power but also the mobility and adaptability of Anglo-Saxon elites in a rapidly changing world.

Conclusion

The Sutton Hoo burial site continues to captivate scholars and the public alike, offering glimpses into the complexities of Anglo-Saxon England. Dr. Gittos’s research, linking Sutton Hoo to the Byzantine Empire, adds a fascinating layer to this story, highlighting the global connections of early medieval England. By reconsidering the identities of those buried at Sutton Hoo, we gain a deeper appreciation for the cultural and historical exchanges that shaped this remarkable site. Sutton Hoo stands not just as a testament to Anglo-Saxon artistry but also as a symbol of England’s place in the interconnected medieval world.