The Doge’s Palace, an iconic symbol of Venice, stands as a testament to the city’s rich history and architectural splendor. Yet, beyond its grandeur as the residence of the Doge and the heart of Venetian governance, the palace housed something darker: its infamous prisons. These cells, deeply intertwined with Venice’s judicial system, hold tales of human suffering, ingenuity, and escape. Let’s delve into the intriguing history of these prisons, the stories of their inmates, and the architectural marvels that made them both feared and fascinating.

A Brief History of the Prisons

Video:

The Early Beginnings (1200s)

The origins of the Doge’s Palace prisons date back to the late 1200s, when cells were established to hold those accused of crimes. These cells bore ominous names like Schiava (slave), Fresca Zoia (fresh joy), and Vulcano. Dark, overcrowded, and unsanitary, these spaces were meant to punish, not rehabilitate. Prisoners endured harsh conditions, with only dim oil lamps providing light amidst the stench of decay.

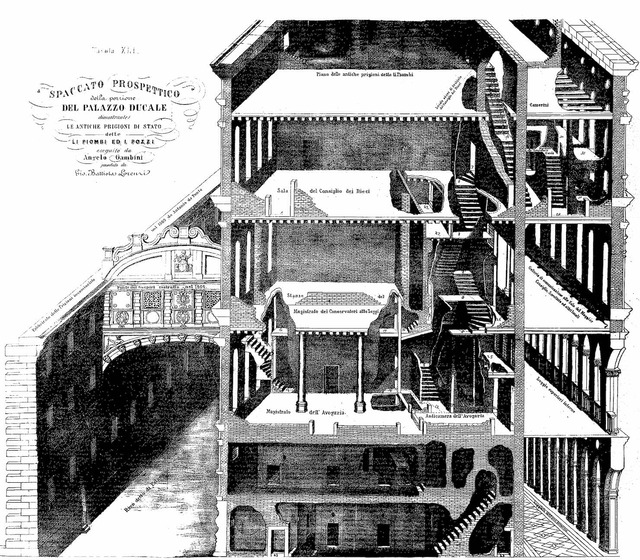

Evolution of Prison Architecture

By the mid-1500s, the Council of Ten sought to improve the prison system’s efficiency. This led to the construction of the pozzi, or “wells,” located on the ground floor of the palace. Despite being an upgrade, these cells were described as “burials of human beings,” a reflection of their inhumane conditions. Meanwhile, the piombi, or “lead chambers,” offered slightly better living conditions for prisoners accused of minor crimes. Positioned beneath the palace’s lead roof, these cells were scorching in summer and freezing in winter but allowed for natural light and ventilation.

The New Prisons: A 16th-Century Marvel

Construction and Design

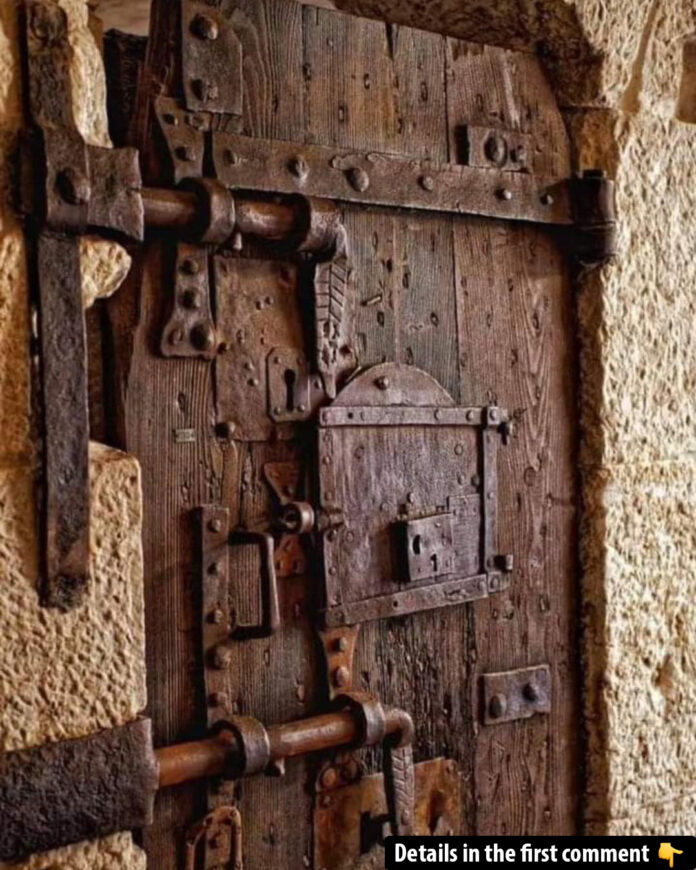

By the late 1500s, the need for a more humane and efficient prison system led to the construction of the New Prisons, located across the canal from the main palace. Designed by Antonio da Ponte—famed for his work on the Rialto Bridge—these prisons incorporated ideas from another designer, Zaccaria Briani, a prisoner-turned-architect. Their collaboration resulted in a structure that emphasized “beauty, comfort, and security.”

Architectural Highlights

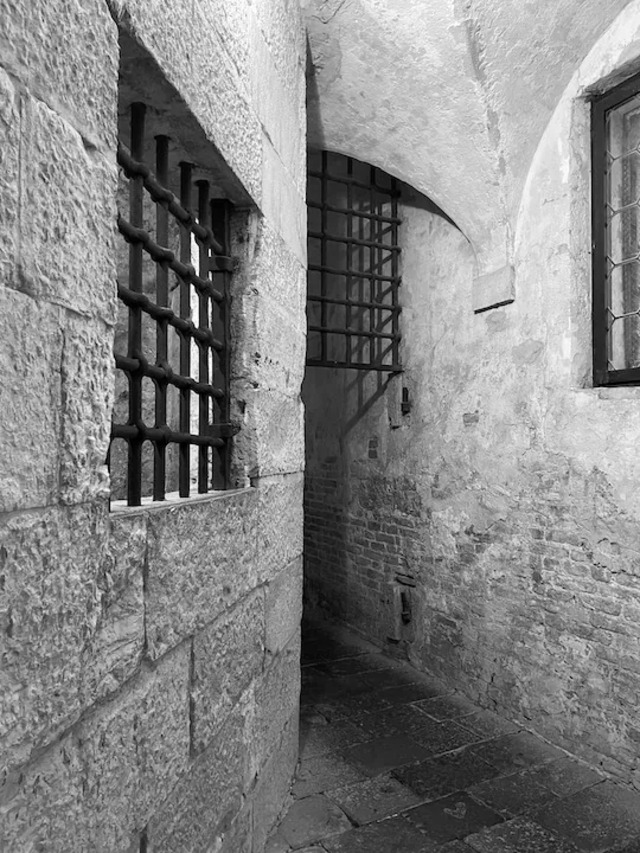

The New Prisons boasted an elegant façade made of Istrian limestone, adorned with intricate lion head motifs and heavy iron grates. Inside, the design prioritized prisoner well-being, with spacious cells, fresh air, and a central courtyard to allow daylight to filter through. A chapel provided spiritual solace, and the isolation of the building ensured security.

Life Inside the Prisons

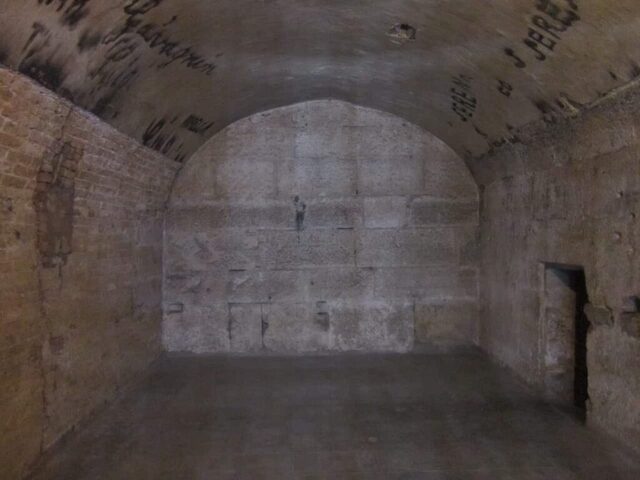

Pozzi: The Burials of Human Beings

The pozzi were infamous for their inhumane conditions. Dark and damp, these cells bred disease and despair. Prisoners were often chained to walls and left in isolation, a grim reflection of medieval punishment ideals. The narrow corridors allowed guards to patrol, ensuring constant surveillance.

Piombi: The Lead Chambers

The piombi, in contrast, offered slightly better living conditions. These cells housed prisoners accused of less severe crimes, such as political dissidents or minor offenders. Despite the extreme temperatures, the presence of light and reduced humidity made them a relative haven compared to the pozzi.

The Escapes

The Legendary Escape of Giacomo Casanova (1756)

The most famous escape from the Doge’s Palace was orchestrated by Giacomo Casanova in 1756. In his memoirs, Histoire de ma fuite des prisons de la République de Venise qu’on appelle les Plombs, Casanova recounts his dramatic getaway. Using smuggled tools, he dug through the ceiling, climbed onto the palace roof, and made his way through courtrooms before descending the Golden Staircase to freedom. His tale, a mix of truth and embellishment, remains one of the most captivating prison break stories in history.

Other Notable Escapes

Casanova wasn’t the only one to escape. Many prisoners broke through walls, bribed guards, or even started fires to facilitate their freedom. Some swam across the canal, while others used outside accomplices to provide boats. These daring escapes underscored the resilience and resourcefulness of those confined within the palace’s walls.

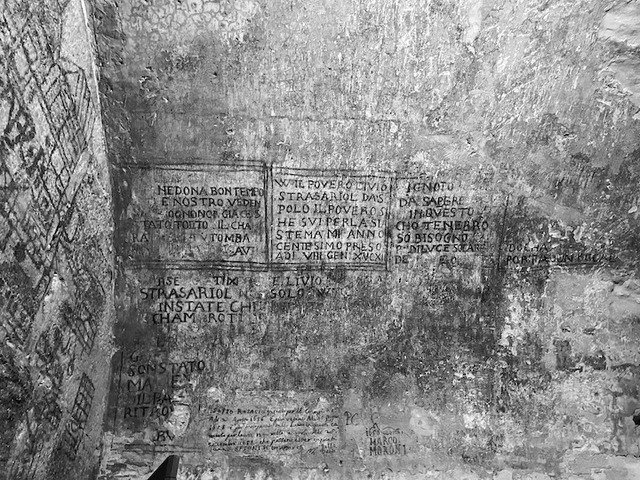

Graffiti: Stories Carved in Stone

The walls of the New Prisons bear witness to the lives of their inmates. Graffiti, etched by prisoners, reveal names, messages, and symbols, offering glimpses into their thoughts and struggles. These carvings serve as a haunting reminder of the human spirit’s ability to endure even the harshest conditions.

Legacy of the Architects

Antonio da Ponte’s expertise and Zaccaria Briani’s firsthand experience as a prisoner resulted in the New Prisons’ groundbreaking design. Briani’s contributions, offered in exchange for his partial freedom, highlighted the intersection of necessity and ingenuity. His unique perspective as both inmate and designer lent a human touch to the otherwise utilitarian structure.

The New Prisons set a precedent for humane incarceration practices in Venice. Today, they stand as a testament to the city’s judicial history, attracting visitors who marvel at their architecture and the stories they hold.

Conclusion

The prisons of the Doge’s Palace are more than just a relic of Venice’s past; they are a window into the city’s complex judicial and architectural heritage. From the harrowing conditions of the pozzi to the relative comfort of the piombi and the innovative design of the New Prisons, these structures reflect a blend of cruelty, compassion, and creativity. Whether through daring escapes or the graffiti left behind, the stories of those who lived within these walls continue to captivate us, reminding us of the resilience of the human spirit.