In the quiet village of Kosenivka, Ukraine, lies a haunting chapter of human history. This small settlement, part of the Neolithic Cucuteni-Trypillia culture, was home to some of the earliest large-scale communities in prehistoric Europe. However, beneath the soil, archaeologists uncovered a tragic story—seven individuals who perished in a house fire approximately 6,000 years ago. This discovery sheds light on the lives, diets, and possibly violent deaths of a Stone Age family, offering a window into the complexities of early human societies.

The Trypillia Culture and Mega-Sites

The Cucuteni-Trypillia culture, flourishing between 5500 and 2750 BCE, is best known for its “mega-sites,” which housed up to 15,000 people. These early urban centers exhibited advanced architecture, including multi-story houses and sophisticated layouts. Trypillia settlements were hubs of agricultural activity and craftsmanship, leaving behind intricate pottery and tools. However, despite the abundance of material artifacts, human remains from this culture are rare. This scarcity makes the findings at Kosenivka uniquely valuable.

Video:

Discovery at Kosenivka

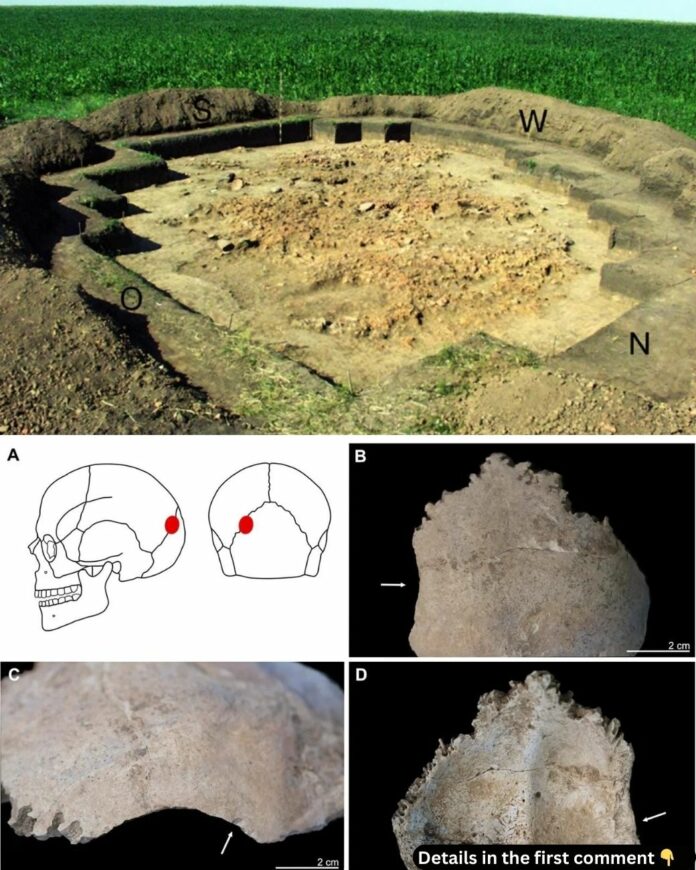

Archaeologists began excavating the site in 2004, uncovering a burned house that held 50 bone fragments belonging to seven individuals. Radiocarbon dating revealed that six of these individuals died between 3690 and 3620 BCE, while a seventh fragment dated approximately 130 years later. The remains included two children, one adolescent, and four adults. Some bones were heavily burned, while others were found intact outside the house. This discovery raised questions about the circumstances of their deaths and the events surrounding the fire.

Video:

Evidence of Violence and Fire

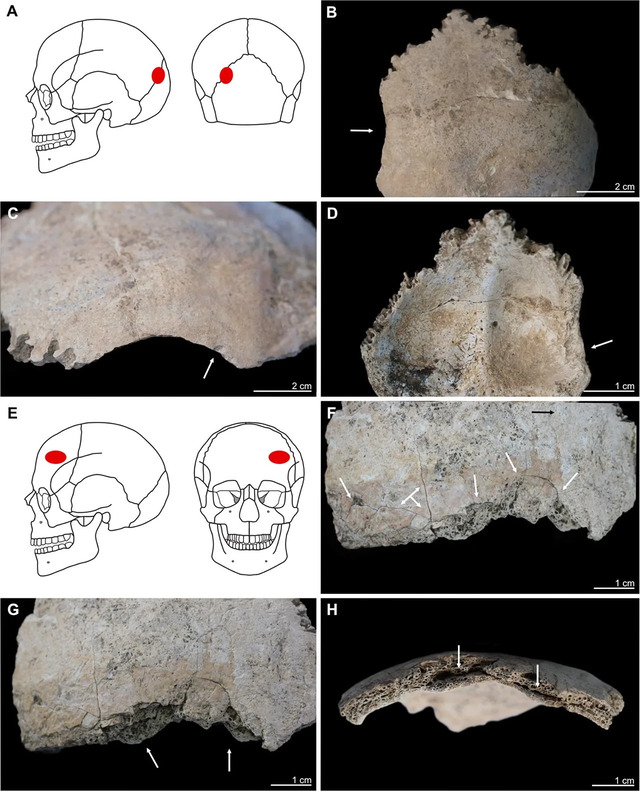

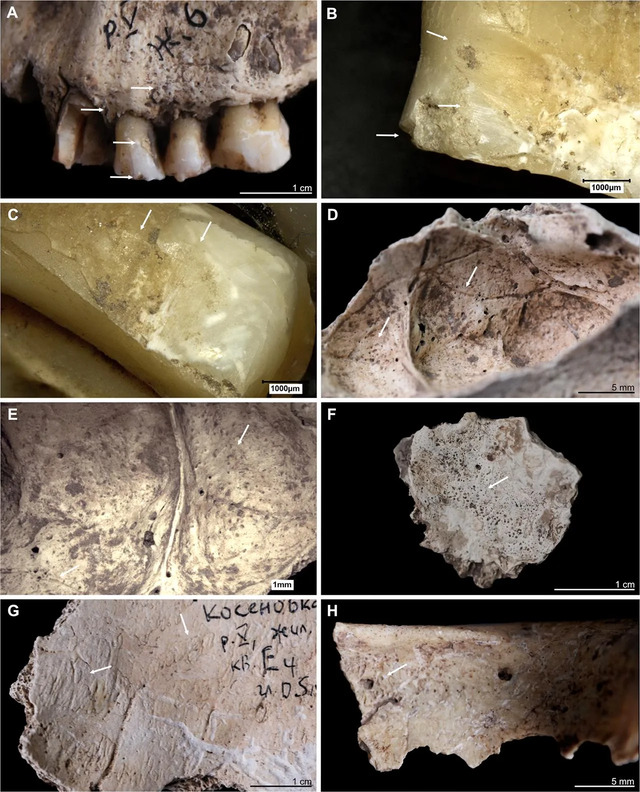

Microscopic analysis of the bones indicated that burning occurred shortly after death, suggesting that the fire was not accidental. Two adults exhibited unhealed cranial injuries, pointing to violent deaths. Archaeologist Jordan Karsten speculated that these individuals might have been victims of a raid, with their house set ablaze during the attack. Such intergroup conflict was not uncommon in the Neolithic era, as communities vied for resources and territorial dominance.

Dietary Insights and Farming Practices

Isotopic analysis of the remains revealed surprising dietary habits. Despite the prevalence of cattle in the region, plant-based foods accounted for 90% of the inhabitants’ protein intake. Meat made up less than 10%, with cattle primarily valued for milk production and manure for fertilizing crops. This reliance on agriculture underscores the advanced farming techniques of the Trypillia people and their ability to sustain large populations through plant cultivation.

Unusual Burial Practices

The fragmented and burned bones at Kosenivka diverged from typical Trypillia burial customs, which often involved extramural burials outside settlements. The placement of these remains within a burned house suggests an unusual or possibly ritualistic burial practice. An isolated skull fragment from a later period hints at the possibility of multistage burials or ceremonial depositions. These deviations offer a glimpse into the cultural complexities of the Trypillia people, who may have blended practical and spiritual elements in their treatment of the dead.

Skeletal Fragments as Historical Archives

Biological anthropologist Katharina Fuchs emphasized the importance of skeletal remains in reconstructing ancient lives. Even small bone fragments can provide insights into the physical conditions, diets, and social structures of past societies. The findings at Kosenivka highlight the value of interdisciplinary research, combining archaeology, anthropology, and advanced scientific techniques to decode the mysteries of prehistoric life.

Lingering Questions

While the Kosenivka findings answer some questions, they also leave many unresolved. What prompted the violence that claimed these lives? Was the fire a deliberate act of destruction or part of a ritualistic practice? How common were such events in Trypillia settlements? These questions continue to intrigue researchers, who see the Kosenivka site as a starting point for deeper explorations into Neolithic Europe.

Conclusion

The story of the Stone Age family at Kosenivka is both a tragedy and a testament to human resilience. Their remains reveal a society capable of building complex communities and sustaining large populations through advanced agricultural practices. At the same time, the violence and fire that ended their lives reflect the inherent challenges of survival in a prehistoric world. As researchers uncover more about the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture, the lessons from Kosenivka remind us of the fragile balance between progress and peril that has defined human history.