Deep within the Amazon rainforest, hidden from the modern world, are approximately 100 uncontacted tribes that have chosen isolation as a shield against the disruptions of the outside world. These communities are not relics of the past; they are vibrant cultures that embody resilience, profound ecological knowledge, and an enduring connection to their environment. However, their existence hangs by a thread, threatened by disease, deforestation, and exploitation.

Who Are the Uncontacted Tribes?

Brazil’s Amazon rainforest is home to the world’s largest concentration of uncontacted Indigenous peoples, with around 100 distinct groups. Most of these tribes reside in remote, forested regions, often avoiding any interaction with outsiders. This isolation stems from traumatic historical encounters, such as the atrocities of the rubber boom in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. During this period, many Indigenous communities were enslaved, displaced, or exterminated. Survivors fled deeper into the rainforest, and the memories of these atrocities continue to shape their desire for seclusion.

The government’s Indigenous affairs department, FUNAI, plays a vital role in monitoring and protecting these tribes. FUNAI’s policies emphasize non-contact and focus on safeguarding their territories from external threats. Yet, little is known about these communities, other than their determination to remain isolated. Some tribes actively avoid outsiders, while others, like the Piripkura, have sporadic contact but prefer to return to the forest.

Video:

Living in Harmony with Nature

Uncontacted tribes demonstrate a unique harmony with their environment, showcasing sustainable lifestyles that have been perfected over generations. Their way of life varies: some, like the Awá, are nomadic hunter-gatherers, constantly moving and building shelters that can be abandoned within hours. Others live in communal houses, cultivating crops such as manioc and bananas in small forest clearings while hunting and fishing to supplement their diet.

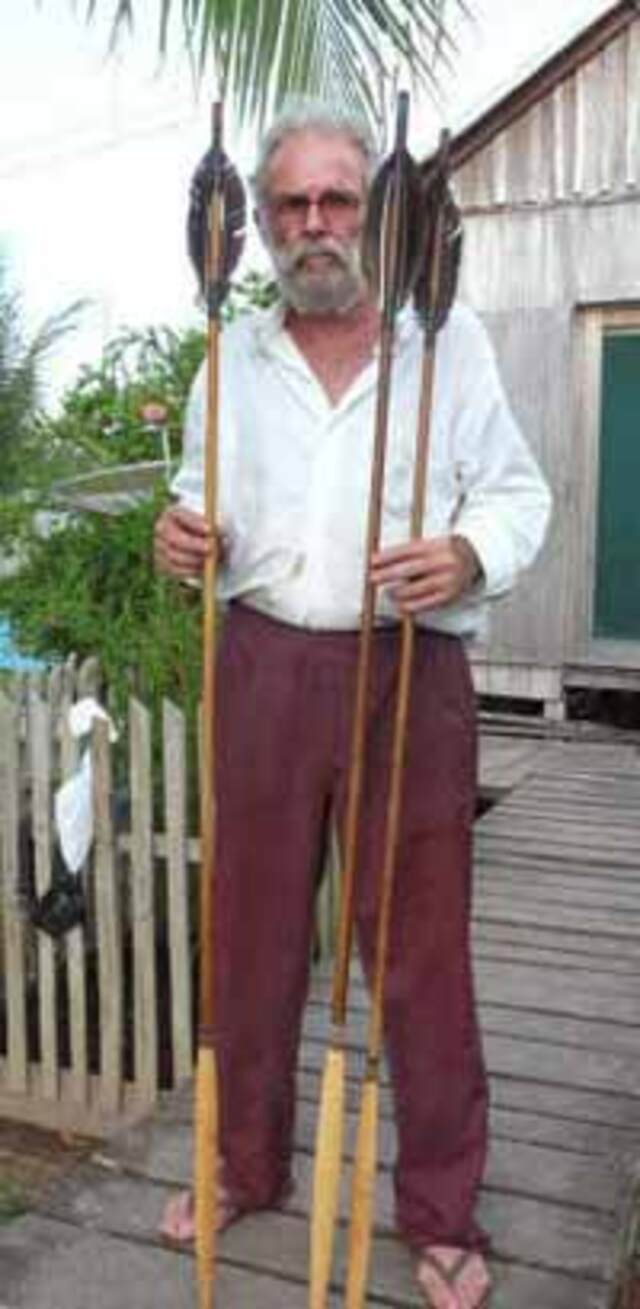

Tools and artifacts found in their camps reveal sophisticated craftsmanship. For example, some tribes use enormous bows and arrows—one bow measuring over four meters was discovered—to hunt game. Their diets include tortoises, with abandoned camps often containing piles of tortoise shells, evidence of their culinary preferences.

These communities’ knowledge of medicinal plants and spiritual practices reveals an intricate understanding of the rainforest’s ecosystem. Their survival depends on maintaining this delicate balance, and their practices reflect a deep respect for the natural world.

Threats to Their Existence

Despite their isolation, uncontacted tribes face numerous threats that jeopardize their survival. One of the most significant dangers is disease. Without immunity to common illnesses like influenza or measles, first contact with outsiders can be catastrophic. Entire communities have been decimated within months of exposure. For instance, the Matis population halved after contact, with many elders and shamans succumbing to pneumonia and other diseases.

Deforestation and land grabs are equally devastating. Illegal loggers, cattle ranchers, and miners encroach upon Indigenous territories, destroying the forests these tribes depend on. Mega infrastructure projects, such as dam construction and road building, further fragment their habitats. In the state of Rondônia, for example, uncontacted groups have been deliberately hunted and their homes bulldozed by ranchers. The last surviving members of the Akuntsu tribe witnessed such atrocities firsthand, leaving only three individuals to tell their story.

The Piripkura and Kawahiva tribes are among the most endangered. The Piripkura—nicknamed the “butterfly people” for their constant movement through the forest—face relentless threats from illegal logging. Temporary measures, such as bans on economic activity within their territories, offer some protection, but enforcement remains weak. Similarly, the Kawahiva live on the run, unable to cultivate crops due to the constant need to evade intruders.

Stories of Survival and Resilience

Amid this grim reality, stories of resilience provide a glimmer of hope. Karapiru, an Awá man, survived a brutal attack on his community by gunmen. For ten years, he lived alone in the forest, relying on his deep knowledge of the land for survival. Eventually, he made contact with colonists and rejoined other Awá. Tragically, he succumbed to COVID-19 in 2021, a stark reminder of the ongoing vulnerabilities these tribes face.

Another poignant story is that of the “last man of his tribe” in Rondônia. For nearly 30 years, he lived in complete isolation after his community was massacred by ranchers. Known for the large holes he dug—possibly as traps for animals or hiding places—he steadfastly avoided all contact. His death in 2022 marked the end of his people’s existence, underscoring the urgency of protecting other uncontacted tribes.

The Role of Advocacy and Protection

Organizations like FUNAI and international advocacy groups play a crucial role in safeguarding uncontacted tribes. FUNAI’s approach of non-contact aims to respect these communities’ wishes while monitoring their territories to deter invasions. Protection posts staffed by field officers serve as the first line of defense against illegal activities. However, more robust measures are needed to enforce land rights and prevent exploitation.

Global awareness and support are essential. Advocacy campaigns have highlighted the plight of uncontacted tribes, pressuring governments and corporations to prioritize Indigenous rights. Recognizing their land rights under international and national law is a critical step toward ensuring their survival. Contact should only occur if and when these communities decide they are ready, allowing them to maintain their autonomy and traditions.

The Importance of Uncontacted Tribes

Uncontacted tribes are not just isolated groups; they are living repositories of knowledge and culture. Their understanding of the rainforest’s ecology offers invaluable insights into sustainable living and biodiversity conservation. By protecting these communities, we also safeguard the forests they steward, which are vital for the planet’s health.

Moreover, their existence challenges conventional notions of civilization and progress. These tribes demonstrate that there are diverse ways of living in harmony with nature, offering alternative perspectives on human development.

Conclusion

The uncontacted tribes of Brazil stand as a testament to human resilience and the enduring connection between culture and environment. However, their survival is precarious, threatened by disease, deforestation, and exploitation. Protecting these communities is not only a moral imperative but also a necessity for preserving the Amazon’s ecological and cultural richness. By valuing and safeguarding their autonomy, we honor their right to live in peace and ensure that their wisdom continues to inspire future generations