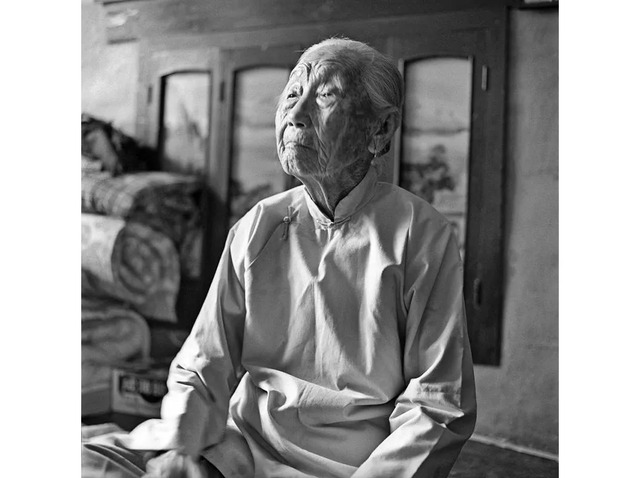

Footbinding, a tradition that endured for over a thousand years in China, was a paradox of beauty, pain, and cultural identity. Rooted in societal norms and Confucian ideals, this practice transformed the lives of millions of Chinese women. Despite its cruelty, footbinding was perpetuated by generations of women and became deeply ingrained in the fabric of Chinese society. Exploring its origins, implications, and eventual decline offers a fascinating window into the complex relationship between culture, beauty, and control.

Origins of Footbinding: The Myth of Yao Niang

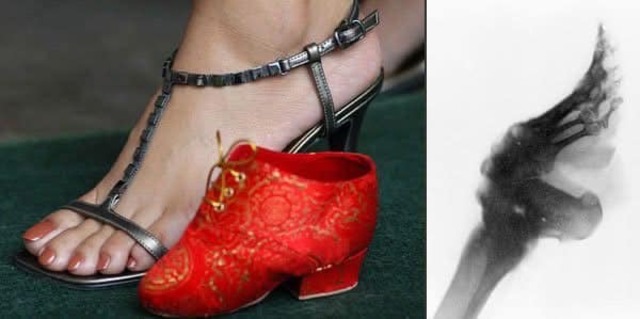

The legend of Yao Niang, a 10th-century court dancer, is often cited as the inspiration for footbinding. She captivated Emperor Li Yu by performing on her toes within a golden lotus, sparking an elite fascination with small, bound feet. This practice quickly spread among court women, becoming a status symbol that symbolized refinement, beauty, and wealth. For families seeking upward mobility, having a daughter with perfectly bound feet—ideally a “Golden Lotus” no more than three inches long—was a ticket to securing advantageous marriages.

Over time, footbinding evolved into an expression of class and femininity. A small foot became a marker of elegance, much like a tiny waist in Victorian England. However, achieving such “perfection” required a brutal and lifelong process of pain and restriction.

Video

Explore the history of foot binding and the stories behind this ancient practice – watch the video to learn more about its cultural impact and the lives it affected.

The Painful Process of Transformation

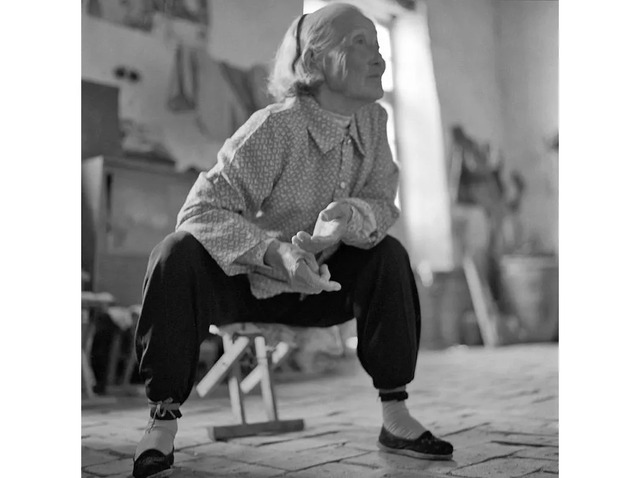

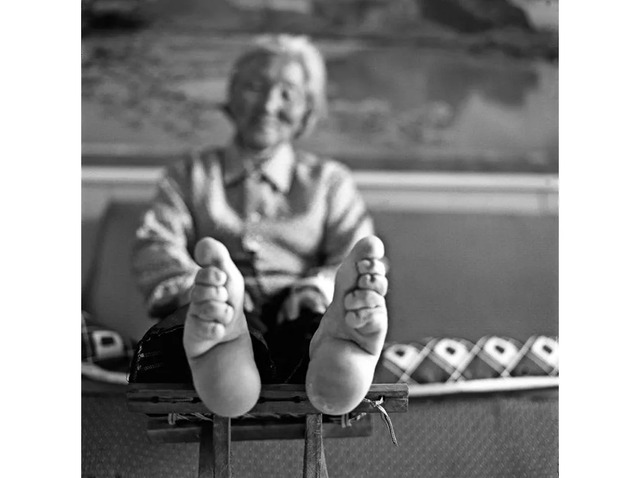

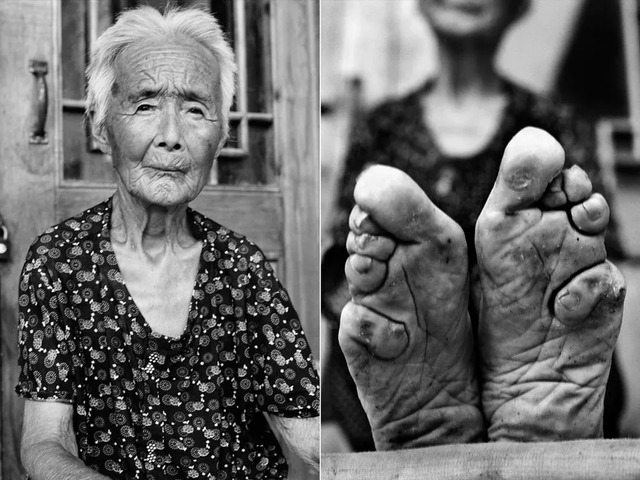

The journey to create a “Golden Lotus” began in early childhood, usually around the age of five or six. A young girl’s feet were plunged into hot water, and her toenails were clipped to prevent infections. Then, the toes—except for the big ones—were broken and pressed flat against the sole of the foot. The arch was bent and strained, and the feet were tightly bound with long strips of silk. This excruciating process was repeated daily, forcing the heel and sole together over time.

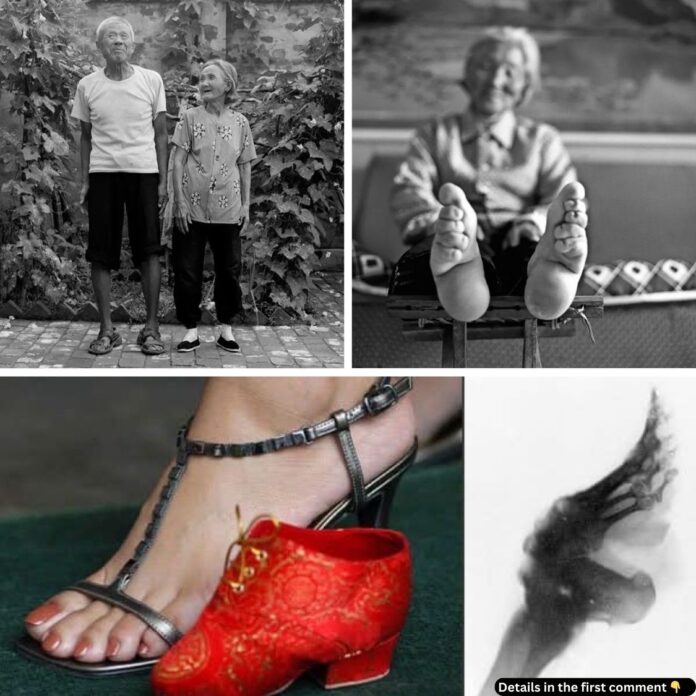

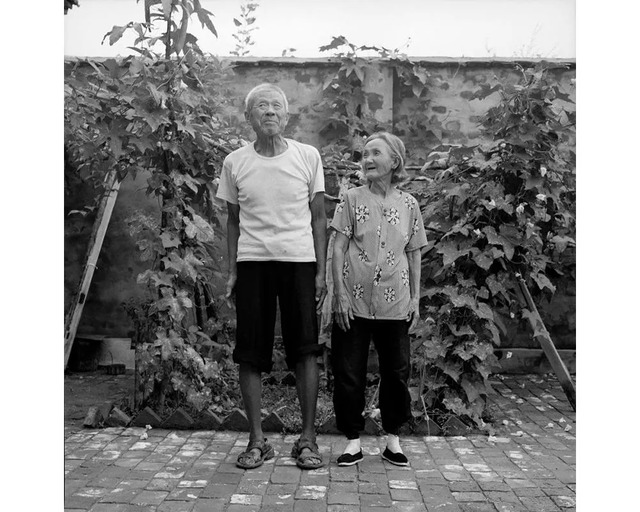

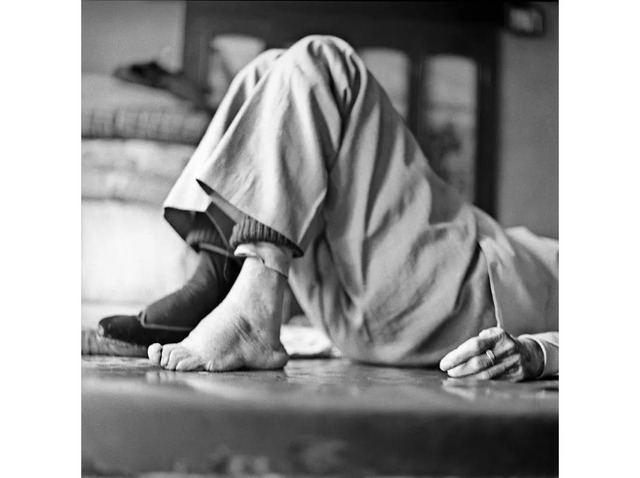

Girls were often made to walk long distances to accelerate the breaking of the arches, while excess flesh was sometimes cut away to hasten the process. After two years of constant binding, the transformation was complete. The result was a foot with a deep cleft that could hold a coin, a physical alteration that was irreversible without undergoing the same agony again. The pain didn’t stop after the binding; the tiny, misshapen feet made walking difficult, leaving women dependent on others for mobility.

Societal Implications of Footbinding

Footbinding was more than a physical transformation—it was a social and cultural phenomenon that shaped the lives of Chinese women. In a society governed by Confucian ideals, bound feet symbolized a woman’s obedience, chastity, and commitment to her family. For many families, a daughter’s bound feet were seen as an investment in her marriage prospects. Smaller feet meant higher status and better opportunities for upward mobility.

The practice also became a form of resistance against foreign rule. During the Mongol and Manchu invasions, footbinding was embraced as a symbol of Han identity. It was an act of defiance, a way for the Chinese to assert their cultural superiority over “barbarian” rulers. Ironically, what began as a fashion statement evolved into a deeply entrenched tradition tied to ethnic pride and societal values.

Women Before Footbinding: Icons of Independence

Before footbinding became widespread, Chinese women played significant roles in politics, literature, and warfare. Shangguan Wan’er (664-710) was a poet and political figure who served as the chief minister to Empress Wu Zetian. Li Qingzhao (1084–1151), a celebrated poet, wrote lyrical verses that continue to inspire readers today. Liang Hongyu (c. 1100–1135), a warrior, commanded troops alongside her husband and earned the title “Lady Defender.”

These women lived during periods when footbinding was not yet the norm, allowing them the physical freedom to pursue their ambitions. However, as Neo-Confucianism took hold during the Song Dynasty, societal expectations shifted, and footbinding became a way to reinforce women’s subjugation.

The Role of Neo-Confucianism

Neo-Confucianism, which emerged during the Song Dynasty, placed immense emphasis on social harmony and moral behavior. For women, this meant chastity, obedience, and diligence. Footbinding became a daily demonstration of these values, a physical manifestation of a woman’s dedication to Confucian ideals. It confined women to domestic spaces and ensured their dependence on male family members, reinforcing patriarchal structures.

Ironically, it was women who perpetuated the practice. Mothers bound their daughters’ feet, believing it was the only way to secure a good future for them. This emotional investment in the tradition ensured its survival for centuries.

The Decline and Legacy of Footbinding

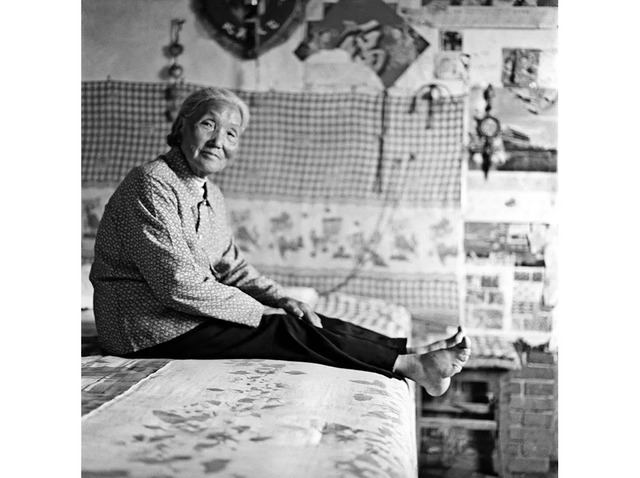

The fall of footbinding began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as reformers and missionaries condemned the practice. The Qing Dynasty made several attempts to ban it, and the Republican government outlawed it in the early 1900s. By the mid-20th century, footbinding had all but disappeared, with the last shoe factory producing lotus shoes closing in 1999.

Today, the remnants of footbinding serve as a stark reminder of the lengths to which societies will go to enforce ideals of beauty and control. The lotus shoes, some no larger than a smartphone, are preserved in museums as symbols of a painful yet fascinating chapter in human history.

Video

Learn about the banned practice of foot binding and its lasting impact on China’s oldest women – watch the video to understand the struggles and history behind this tradition:

Conclusion: Lessons from a Millennium-Long Tradition

Footbinding endured for over a thousand years because it was deeply tied to societal values, cultural identity, and familial aspirations. While it is now universally condemned, the practice offers valuable lessons about the complex interplay between tradition, beauty, and power. It is a reminder that the history of women is not a linear progression from oppression to liberation, but a tapestry of resilience, sacrifice, and cultural evolution.

The story of footbinding is both tragic and illuminating, a testament to the enduring human desire to shape and control identity through the body. As we reflect on this practice, we are challenged to question the societal norms that define beauty and the sacrifices made in its name.