Beneath the cold waters off Sweden’s west coast, a groundbreaking discovery has surfaced—a 14th-century shipboard cannon, possibly the oldest of its kind in Europe. Found by chance yet rich with history, this remarkable artifact sheds light on the evolution of naval warfare during a turbulent era of piracy and maritime conflict. It’s a story of ingenuity, power, and survival, offering a rare glimpse into the past when early artillery began to change the course of history.

A Remarkable Discovery

The cannon was discovered 20 meters beneath the surface near Marstrand, a historically significant port that served as a critical link between Western Europe and the Baltic Sea during the 14th century. Unlike many artifacts that may have been mere cargo, this cannon was identified as a functional shipboard weapon, still loaded with a charge in its powder chamber. This detail suggests it was ready for battle at the time of its submersion, offering a snapshot of a perilous moment in history when piracy and naval warfare dominated the seas.

Marstrand, renowned for its bustling port, was no stranger to maritime conflicts. As a hub of trade and travel, it was a target for piracy and a stage for naval battles. This cannon, likely part of a ship’s defensive arsenal, represents a time when technological advancements in weaponry began transforming the nature of maritime warfare.

Video:

Dating and Analysis

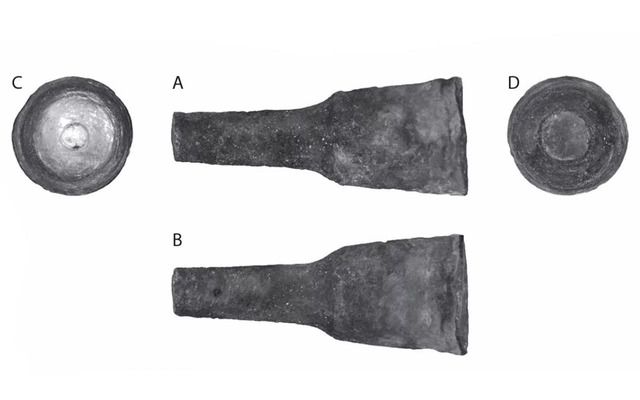

One of the most intriguing aspects of this discovery is the precise dating of the cannon. Thanks to the preserved remains of its charge, researchers used radiocarbon dating to determine its origin in the 14th century. This finding challenges existing typologies of early artillery, which had previously placed similar funnel-shaped cannons in the 15th or 16th centuries. The Marstrand cannon proves that such designs were in use at least a century earlier, pushing back the timeline of artillery development.

Further analysis of the cannon’s metal composition revealed it to be a copper alloy with approximately 14% lead and minimal tin content. This composition, while far from ideal for casting durable cannons, reflects the experimental phase of artillery manufacturing during this period. Researchers suggest that the copper likely originated from present-day Slovakia, while the lead could have been sourced from England or the Poland-Czech border region. These findings underscore the interconnectedness of medieval Europe, where resources and technologies flowed across borders, shaping advancements in warfare.

Insights into Early Naval Artillery

The Marstrand cannon provides valuable insights into the evolution of naval artillery. Its funnel-shaped design and early use of cartouches—textile packaging for powder charges—highlight the ingenuity of medieval engineers. Cartouches, which simplified the loading process, were thought to have been introduced much later, but this cannon proves otherwise.

This discovery also offers a window into the strategic importance of shipboard artillery during the 14th century. As piracy and naval conflicts escalated, cannons became a crucial component of maritime defense. The Marstrand cannon’s presence on a ship suggests that vessels were becoming increasingly armed to navigate the treacherous waters of medieval Europe. Such advancements in weaponry not only changed the dynamics of naval warfare but also set the stage for the more extensive use of artillery in later centuries.

The Mystery of the Ship

While the cannon itself has been meticulously studied, the ship it once belonged to remains a mystery. Its identity, purpose, and ultimate fate are questions that researchers are eager to answer. The cannon’s presence suggests the ship was engaged in conflict, either as a victim of piracy or as a participant in a naval battle. However, centuries underwater have likely left the ship significantly deteriorated, complicating efforts to locate and document it.

Despite these challenges, the research team is determined to conduct a comprehensive survey of the seabed in the area. By piecing together fragments of the wreck and its surroundings, they hope to uncover more details about the ship and the historical context in which it operated. Such findings could provide invaluable insights into 14th-century shipbuilding techniques, trade routes, and the broader maritime landscape of the time.

Broader Implications

The Marstrand cannon is more than just an artifact; it is a testament to the technological experimentation and geopolitical dynamics of the 14th century. Its discovery highlights the rapid evolution of weaponry and the strategic importance of maritime power during a turbulent era. It also underscores the interconnectedness of medieval Europe, where resources, knowledge, and innovations were exchanged across regions, shaping the course of history.

Moreover, this find challenges preconceived notions about early artillery and its role in naval warfare. By pushing back the timeline of funnel-shaped cannons and revealing the early use of cartouches, the Marstrand cannon offers a fresh perspective on the ingenuity and adaptability of medieval engineers. It also serves as a reminder of the risks and rewards of maritime exploration, where technological advancements often determined the success or failure of a voyage.

Conclusion

The discovery of the Marstrand cannon marks a significant milestone in the study of medieval maritime history. As one of Europe’s oldest shipboard artillery pieces, it provides a rare glimpse into the technological and strategic innovations of the 14th century. While the ship it belonged to remains a mystery, ongoing research promises to uncover more about this turbulent period, offering insights into the interplay of warfare, trade, and technological progress.

Through the meticulous work of researchers and the application of modern technologies like radiocarbon dating and metal analysis, the Marstrand cannon has not only enriched our understanding of medieval Europe but also inspired a renewed appreciation for the complexities of its maritime history. As archaeologists continue to explore the depths of the sea, who knows what other stories lie waiting to be told?