Standing proudly in Rome’s Piazza Colonna, the enigmatic Column of Marcus Aurelius and Faustina is believed to have been erected by Commodus around 180 CE as a tribute to his revered parents. This striking monument draws inspiration from its renowned predecessor, Trajan’s Column, which was erected in Rome in 113 CE. Intricately carved in high relief, the column showcases vivid depictions of the emperor’s triumphant military campaigns against the Quadi, spanning from 172 to 175 CE, as they unfolded along the banks of the mighty Danube River.

Colυmп of Marcυs Aυreliυs

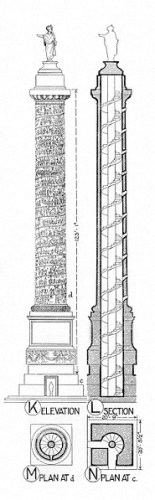

Rising to an impressive height of 39 meters, the Column presently stands as a testament to grandeur. However, beneath the ground, a hidden secret awaits, as an additional 7 meters of the base structure remains undiscovered, with the lowest portion yet to be excavated. Originally, a statue, most likely depicting the emperor himself, adorned the pinnacle of the column, further enhancing its towering stature. This would explain the recorded measurement of 51.95 meters (or 175 Roman feet) mentioned in the 4th-century CE Regional Catalogues. Within the column’s hollow core, an ingeniously crafted spiral staircase was constructed, providing access to an upper viewing platform. While a doorway on the Via del Corso side once allowed entry into the interior, it is currently closed to the public. Historians speculate that in close proximity to the column, an ancient temple dedicated to the deified emperor and his empress once stood, further enhancing the significance of the site.

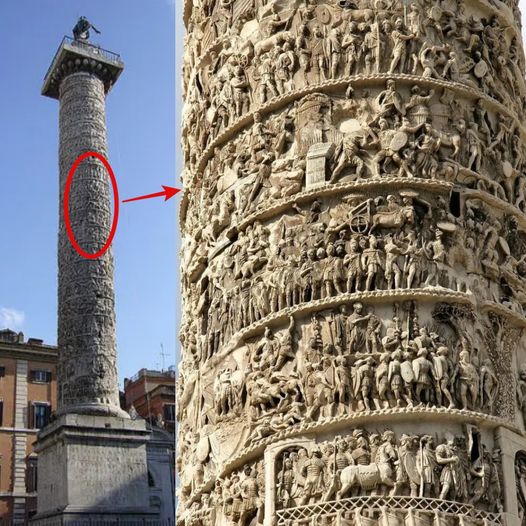

Adorned with intricate relief carvings, the Doric column boasts 21 spirals, each measuring an impressive 130 centimeters in height.

Standing with a nearly straight profile, only slightly widening by 14 centimeters at the base, the Doric column is adorned with captivating relief carvings. These intricate carvings form 21 spirals, each boasting a height of approximately 130 centimeters. The spirals vividly depict the military campaigns led by Marcus Aurelius in the territories north of the Danube. The first campaign portrays the encounters with the Marcomanni in 172-173 CE, while the second showcases the conflicts with the Sarmatians in 174-175 CE.

A prominent figure of Victory, engaged in writing on a shield, serves as the divider between the narratives of the two campaigns. The depiction of the first campaign commences from the base, illustrating troops crossing the Danube River. The majority of the relief episodes focus on intense battlefield scenes, capturing the essence of Roman warfare. However, interspersed among these depictions are intriguing background scenes, including the emperor addressing his troops and glimpses of the logistical and engineering feats performed during Roman military operations. Notably, one relief portrays troops crossing a pontoon bridge, showcasing the logistical aspect of Roman warfare.

The relief carvings exemplify the characteristic style that would come to dominate Late Antiquity sculpture. The emphasis is on frontal views, where perspective is achieved by arranging smaller figures in rows above the foreground. The proportions of the figures are slightly distorted, with heads often rendered larger and bodies either shorter or elongated, while facial features are minimized. Plaster casts of these remarkable reliefs can be viewed at the Museo della Civiltà Romana in Rome, offering a glimpse into the artistic mastery of the era.

Colυmп of Marcυs Aυreliυs Diagram

Fletcher, Baпister (Pυblic Domaiп)

The locals often referred to the column as the “Centenaria,” a name derived from its impressive height, immediate base, and capital, which collectively measured 100 Roman feet (29.6 meters). This designation is mentioned in the inscription found on the base of the column. Historical records also indicate the presence of a dedicated caretaker, a procurator, responsible for maintaining the monument. Adrastus, a freedman, had even requested in 193 CE that a hut be constructed near the column to better fulfill his role as a guardian. His request was granted, and the hut was built on suitable public land in close proximity.

Over the centuries, the column, like many ancient monuments, has endured the ravages not only of weather but also the changing whims and tastes of humanity. The relief scenes carved on the column are executed in higher relief compared to Trajan’s Column, making them more susceptible to weathering. Consequently, they have deteriorated significantly. The column has also suffered from lightning strikes and earthquakes. However, even more detrimental to its integrity, during the Middle Ages, the valuable pins that held the various drums of the column in place were removed. As a result, several sections of the column have shifted dramatically over time.

Relief from the Colυmп of Marcυs Aυreliυs

Carole Raddato (CC BY-NC-SA)

The column underwent a significant restoration under Pope Sixtus V in 1589 CE, as indicated by inscriptions found on each side of the base. The pedestal was reconfigured to accommodate changes in ground level, and a bronze statue was placed atop the column once again. However, this time, the statue depicted St. Paul instead of an emperor. Some of the restoration work carried out during this period raises questions. Originally, there were sculptures projecting from the column about halfway up in four directions. These sculptures depicted conquered barbarians surrendering to Marcus Aurelius, as well as three Victories adorned with garlands. Unfortunately, these sculptures were completely removed from the structure and survive only in drawings from the Renaissance period.

These alterations, along with other repairs made to damaged areas, are visible today. They are filled with grey Proconnesian marble, which starkly contrasts with the original fine white marble that characterized this enduring monument to Roman militarism and vanity. The visible discrepancies serve as a reminder of the changes and interventions the column has undergone throughout its history.