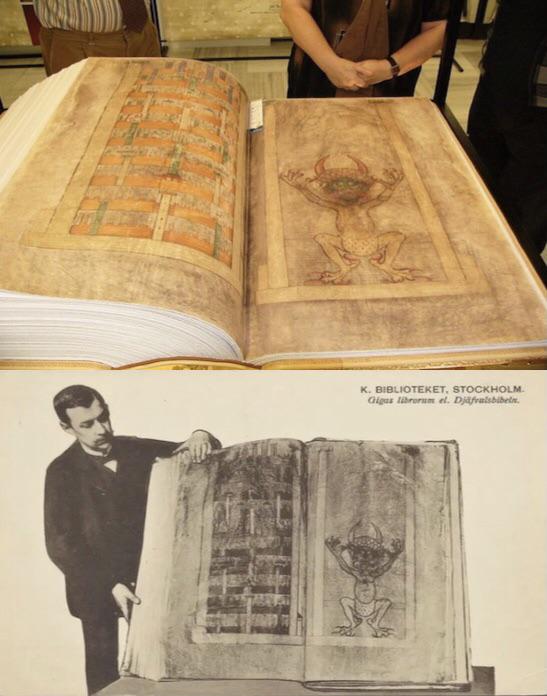

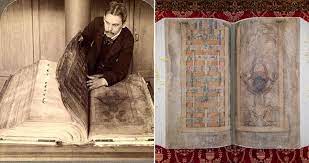

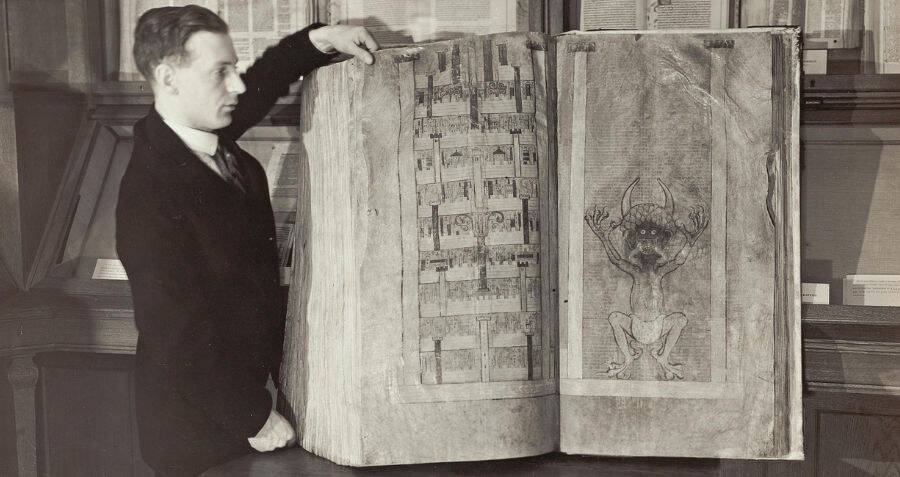

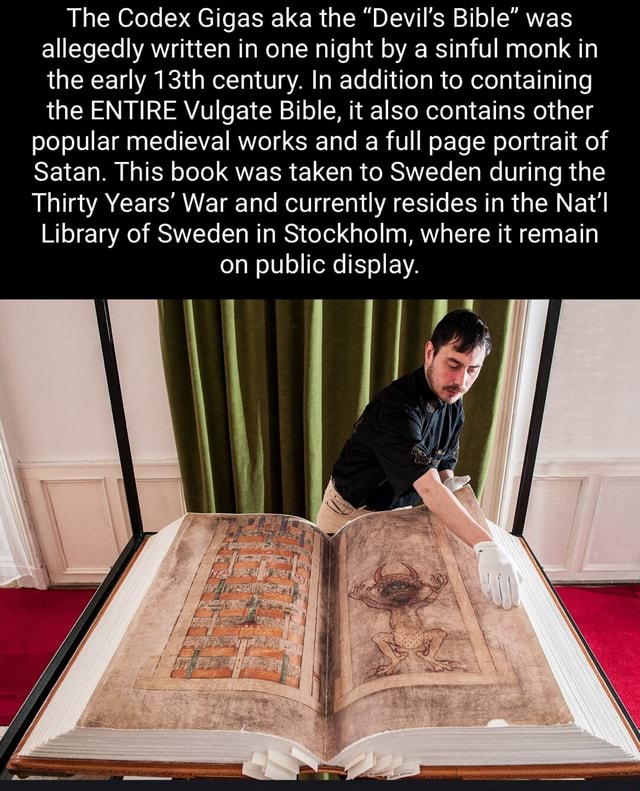

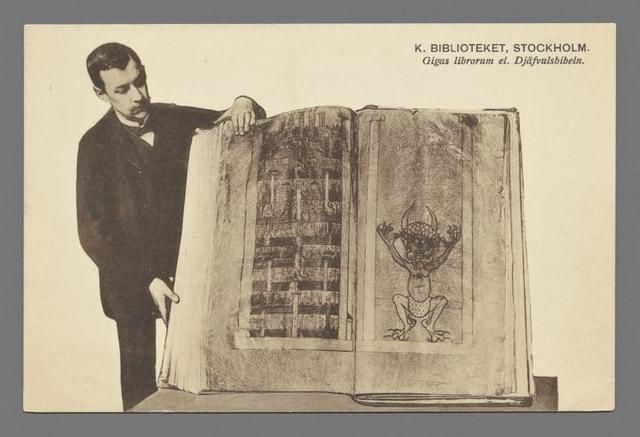

The Codex Gigas, also known as the Devil’s Bible, gained fame for three remarkable reasons. Firstly, it holds the distinction of being the largest illuminated medieval manuscript in existence. Secondly, its impeccable and uniformly written text is so astonishingly well-executed that it appears almost superhuman in its precision. Lastly, the codex features a prominently displayed full-page portrait of the Devil.

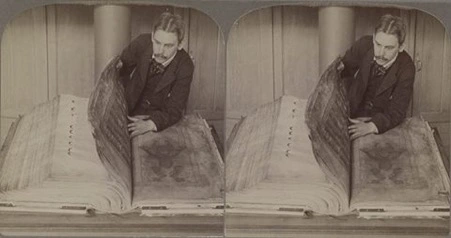

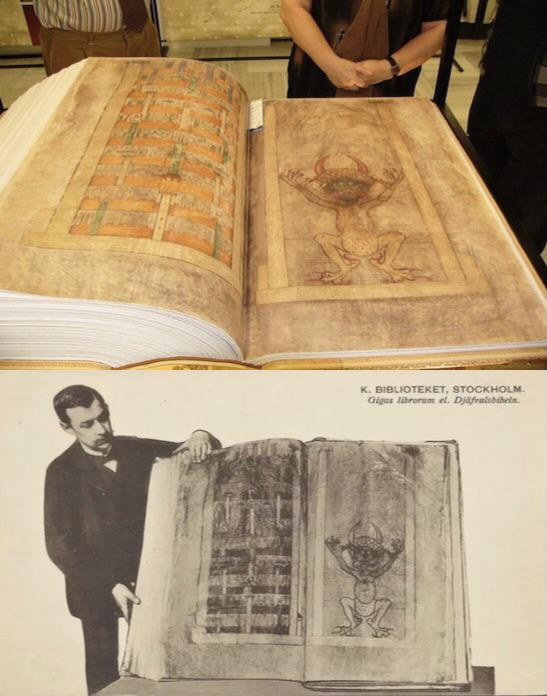

Believed to have been written between 1204 and 1230, this extraordinary book measures 92 cm in height, 50 cm in width, and is a substantial 22 cm thick, weighing approximately 79 kg. Originally, it consisted of 320 vellum leaves, reportedly made from the skins of 160 donkeys. If each donkey contributed two pages, the skins would have covered an area of 142.6 square meters. However, at some unknown point in time, twelve leaves were removed for reasons that remain a mystery. While large illuminated bibles were not uncommon in monastic book production, the page size of the Codex Gigas is exceptionally large, even within this category.

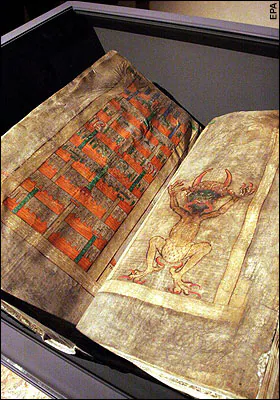

The manuscript is written using the Carolingian minuscule script, a popular and highly legible medieval writing style. It contains numerous intricate illuminations, predominantly featuring decorated letters and geometric or plant-based designs. Notable exceptions are the depiction of a squirrel perched atop an initial, a portrait of Josephus, and the infamous caricature-like portrayal of the Devil. Additionally, there are two images representing Heaven and Earth, complete with the sun, moon, stars, and a planet depicted as a sea without land masses.

The Codex Gigas is bound in a single volume with thick wooden boards covered in white leather adorned with blind stamps, one of which has been observed elsewhere. Each board features metal fittings – one in each of the four corners and one in the center – all exquisitely decorated and equipped with a raised button upon which the book was intended to rest. Two additional metal fittings can be found on the back, one of which has a hole that may have been used to chain the Codex to a piece of furniture, preventing its removal. The binding suffered damage in a fire, and in 1819, an artisan in Stockholm re-bound the codex at a cost of 78 riksdaler for materials and labor, an amount equivalent to the purchase of two cows at that time.

Contained within the Codex Gigas are several significant texts, including the entire Latin Bible, Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae (also known as Etymologies), Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews, Cosmas of Prague’s Chronicle of Bohemia, as well as numerous writings describing magic formulas, exorcism rituals, and a calendar.

A National Geographic documentary featured interviews with specialists in the fields of writing and forensic analysis, who reached the conclusion that the Codex Gigas was written by a single scribe. They further determined that the writing alone would have required a minimum of 5 years of full-time, dedicated labor, with an additional 20 years for the intricate decorations. The scribe would have needed to rule each page before forming the letters, and a reasonable goal would have been to write 100 lines per day.

What adds to the intrigue of the Codex Gigas is the nature of its writing. There are no discernible signs of aging, disease, mood variations, or natural evolution in style. In fact, its remarkable length, size, detail, and perfection are so extraordinary that a legend regarding its origins was recorded during the Middle Ages. According to the legend, the codex was written by a monk who had broken his monastic vows and was sentenced to be walled up alive. In order to avoid this harsh punishment, he made a pact to create a book that would encompass all human knowledge and promised it would be completed in a single night. Realizing he could not fulfill this monumental task alone, he called upon the fallen angel Lucifer to assist him in exchange for the souls of the monks. The devil accepted the deal, and as a gesture of gratitude for his help, the monk included a portrait of Lucifer within the codex.

This legend surrounding the creation of the Codex Gigas adds a mysterious and supernatural element to its story, further fueling fascination with the manuscript and its origins.

The depiction of the devil in the Codex Gigas, wearing a white loincloth with small comma-shaped red dashes, which have been interpreted as the tails of ermine furs, is indeed intriguing. The inclusion of ermine fur, which was a symbol of sovereignty, could potentially suggest a political commentary. Additionally, the devil’s forked tongue, a symbol used in the Bible to denote a deceitful human being, adds further symbolism to the image.

Regarding the timeline of the manuscript’s eventful life:

- Between 1204 and 1230, the Codex Gigas was likely written at the Podlažice Monastery in the Kingdom of Bohemia, which is now part of the Czech Republic.

- In 1295, Podlažice pledged the manuscript to the nearby Sedlec Monastery, which eventually sold it to the Benedictine Order of Břevnov Monastery.

- In 1594, Emperor Rudolf II borrowed the Codex and placed it in his castle in Prague.

- In 1648, Prague was sacked by the Swedish army, and the manuscript ended up in Queen Christina’s library inside Castle Tre Kronor.

- In 1697, the castle burned down, resulting in the destruction of 18,000 books and 5,700 manuscripts. The Devil’s Bible survived because someone threw it out of a window, injuring a bystander and damaging the book’s binding.

- In 1768, the manuscript was installed in the newly-built Stockholm Palace.

- In 1819, the book was re-bound.

- In 1878, the Codex was moved to a new library building in the Hümlegården park through sleight.

- In 2007, the manuscript was loaned to Prague, where it was displayed in the National Library.

- In 2018, it became a permanent display in the Treasury Room of the Royal Library in Stockholm. The entire work is viewable in digitized form on the library’s website, allowing people to explore it even if they cannot visit Stockholm in person.

The timeline provides a glimpse into the Codex Gigas’ journey through history, from its creation in the 13th century to its current location in the Royal Library in Stockholm.