A groundbreaking study has revealed how the ancient Mesopotamians experienced and expressed emotions, offering a window into one of history’s earliest civilizations. Based on Akkadian texts from over 2,500 years ago, researchers uncovered the fascinating connections between emotions and specific body parts. This unique perspective challenges modern assumptions about the universality of emotional expression.

Ancient Mesopotamian Views on Emotions

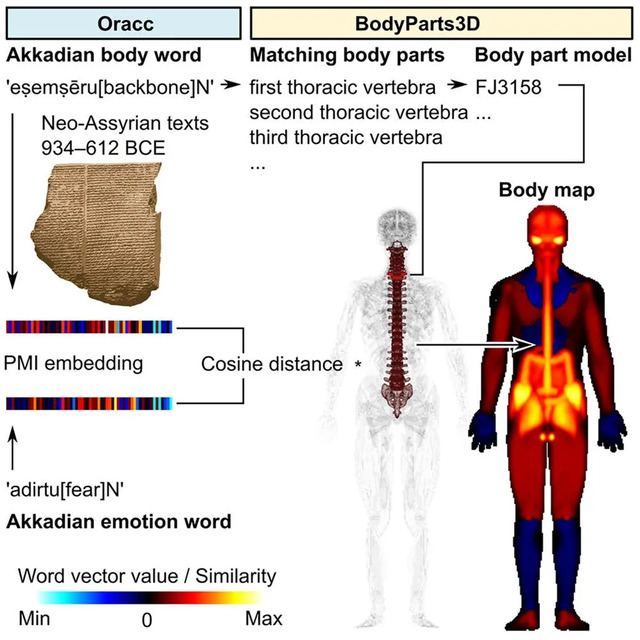

The study analyzed over one million words from Akkadian texts written in cuneiform on clay tablets between 934 and 612 BCE. These records, meticulously examined by a multidisciplinary team led by Professor Saana Svärd from the University of Helsinki, provide an unparalleled glimpse into the emotional lives of Mesopotamians.

Akkadian scribes, the elite literate class of ancient Mesopotamia, documented emotions not merely as abstract concepts but as deeply connected to anatomy. For the Mesopotamians, emotions were inseparable from the body, anchored in vital organs like the heart and liver.

Video:

Happiness, Love, and Anger in Mesopotamian Anatomy

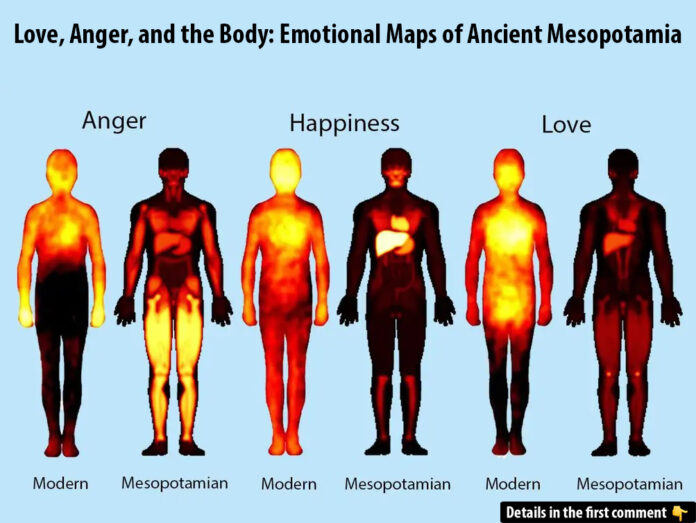

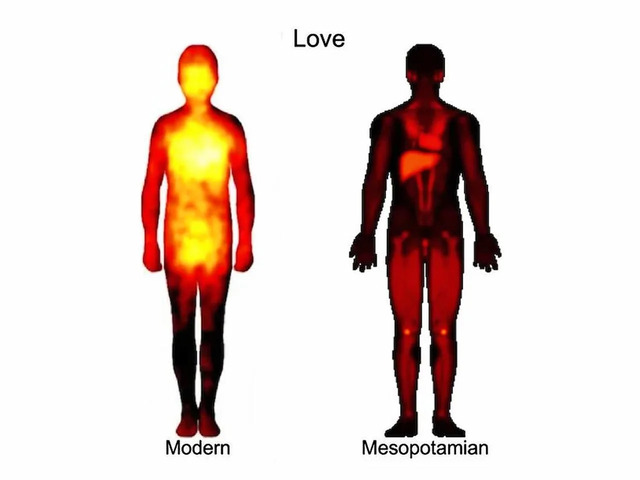

The Mesopotamians linked specific emotions to distinct parts of the body, creating a unique “emotional map” that diverges significantly from modern interpretations.

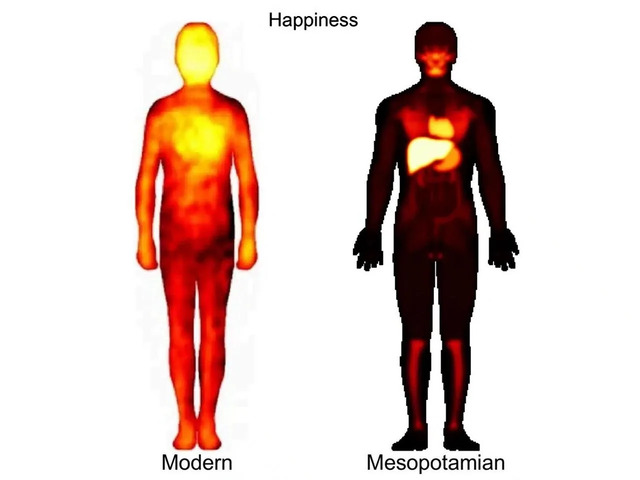

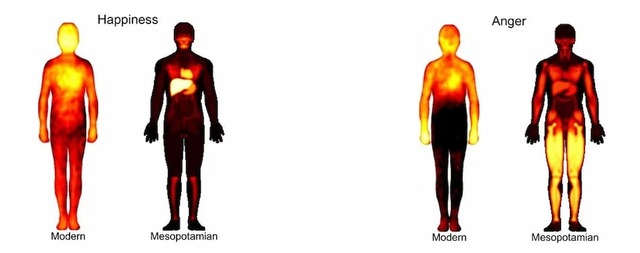

Happiness Resided in the Liver

In Mesopotamian texts, the liver was synonymous with happiness. Descriptions of joy often included terms such as “open,” “shining,” and “full,” emphasizing the organ’s symbolic and functional importance. Cognitive neuroscientist Juha Lahnakoski, a researcher on the project, highlighted the parallels between this ancient understanding and modern body maps of happiness, although the liver’s glow is a distinctive Mesopotamian interpretation.

Anger Was Felt in the Feet

While modern humans often associate anger with the upper body or hands, Mesopotamians felt anger in their feet. Words like “heated” and “enraged” described an emotion that symbolized movement or confrontation, a reflection of how their culture may have viewed the physical manifestations of anger.

Love Encompassed the Liver, Heart, and Knees

Love, a universal emotion, had a multifaceted significance for the Mesopotamians. While modern cultures often associate love with the heart, the Akkadian texts also linked it to the liver and knees. The knees symbolized emotional intensity and vulnerability, as bending or falling to one’s knees was seen as a powerful physical metaphor for devotion and submission.

Methodology and Modern Comparisons

The study used corpus linguistics, a technique refined at the Center of Excellence in Ancient Near Eastern Empires, to analyze the linguistic descriptions of emotions in the Akkadian texts. This approach enabled researchers to map emotional terms to body parts with remarkable precision.

The findings were compared with modern body maps of emotions, such as those created by Finnish researcher Lauri Nummenmaa. While there are striking similarities in the mapping of joy and love, the Mesopotamian association of anger with the feet and happiness with the liver reflects unique cultural interpretations. As Professor Svärd noted, “Texts are texts, and emotions are lived and experienced.” The study underscores the challenges of bridging the gap between ancient linguistic records and modern physiological understandings.

Implications for Understanding Human Emotions

The discovery offers profound insights into the shared and divergent ways humans have experienced emotions across time and cultures. While some emotional expressions appear universal, such as the connection between love and the heart, others are uniquely shaped by the cultural and anatomical knowledge of the time.

For the Mesopotamians, their rudimentary yet significant understanding of anatomy shaped their emotional associations. Organs like the liver were not only central to physical health but also symbolic of emotional well-being. This perception reveals how deeply intertwined emotions and physicality were in their worldview.

Future Research Directions

This study opens exciting possibilities for further exploration of emotional expressions in historical texts and modern contexts. The research team plans to analyze a 20th-century English text corpus of 100 million words and extend their work to Finnish data. These comparisons may uncover patterns in how emotions are linked to the body across different cultures and time periods.

By examining these intercultural differences, researchers hope to identify universal aspects of emotional experience and understand how cultural and linguistic factors shape our perception of emotions.

Conclusion

The Akkadian texts from ancient Mesopotamia reveal a fascinating emotional landscape where love shone in the liver, anger burned in the feet, and happiness radiated through the body. These insights challenge modern assumptions about emotional expression and highlight the complex interplay between culture, anatomy, and language.

As we continue to explore the emotional lives of ancient civilizations, such discoveries remind us of the shared humanity that connects us across millennia. Through the lens of Akkadian texts, we gain not only a deeper understanding of Mesopotamian culture but also a richer appreciation of how emotions have shaped the human experience throughout history.