Giovanni Battista Bugatti: The Infamous Executioner of the Papal States

Introduction

Giovanni Battista Bugatti, more notoriously known as Mastro Titta, stands as one of the most intriguing figures in the annals of history. Born in Senigallia in 1779, he served as the principal executioner for the Papal States, a role he held for an astounding 68 years. Over his long career, Bugatti executed 514 people, a number that starkly highlights the grim duties he performed. His meticulous records, however, note 516 executions, with two excluded due to being carried out by his assistants. Mastro Titta’s legacy is a blend of fear, fascination, and a deep dive into the darker aspects of human history.

Early Life and Career

Bugatti’s career began at the tender age of 17 in 1796. His initial foray into the world of executions set the stage for what would become a lifetime dedicated to this morbid profession. His first documented execution in Valentano was of Marco Rossi, a man who murdered his uncle and cousin over an inheritance dispute. This event marked the beginning of Bugatti’s long and grim career. The name “Mastro Titta” soon became synonymous with the executioner, not just in Rome but across the Papal States, cementing Bugatti’s place in history.

Tools and Legacy

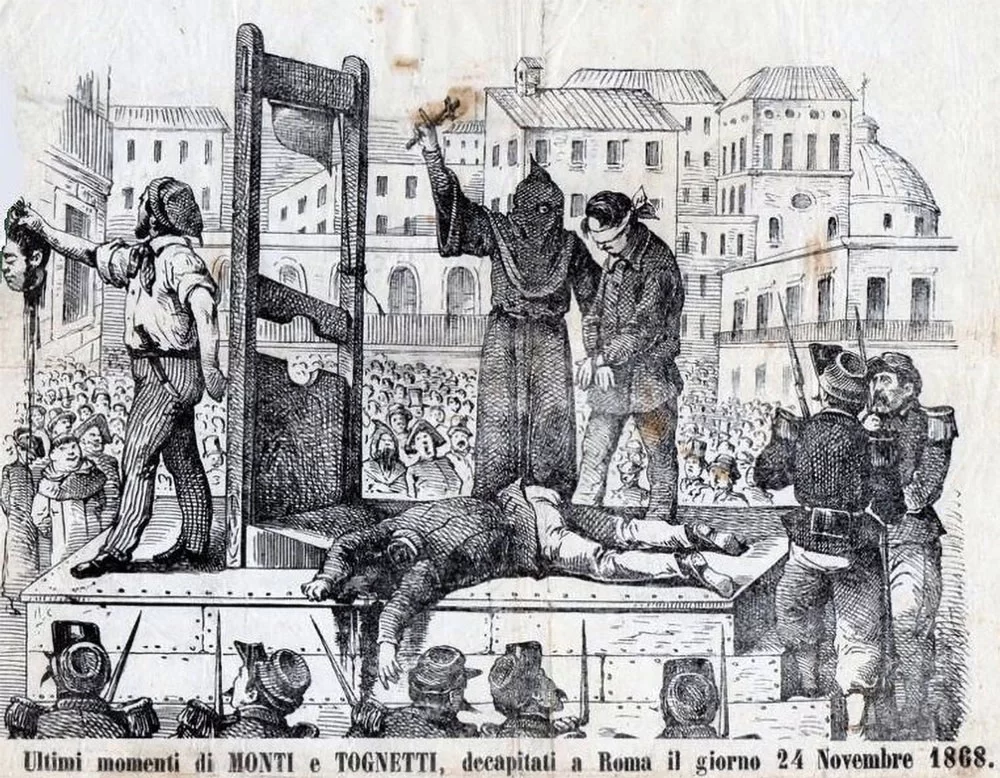

Mastro Titta’s tools of the trade, including his blood-stained clothes, axes, and unique guillotines, are now displayed at the Museum of Criminology in Rome. The guillotine, in particular, features a straight blade and V-shaped neckpiece, a design that sets it apart from others of its kind. These artifacts offer a chilling glimpse into the past, preserving the memory of a man whose job was to carry out the ultimate punishment.

In 1864, after nearly seven decades of service, Bugatti was replaced by Vincenzo Balducci. Pope Pius IX granted Bugatti a monthly pension of 30 scudi, recognizing his long service. Despite his retirement, the legacy of Mastro Titta continued to loom large over Rome, with his name enduring as a byword for executioner.

Execution Sites and Notoriety

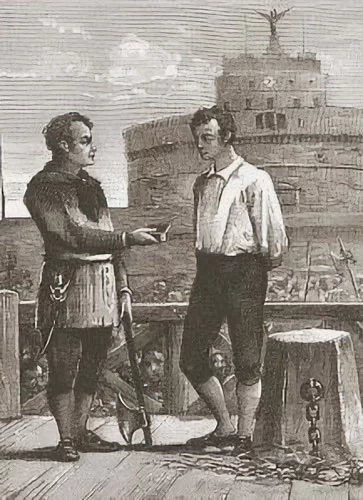

Bugatti’s work took him across the pontifical territory, and his presence was a harbinger of death. Executions were a public spectacle, often held in prominent locations such as Piazza del Popolo, Campo de’ Fiori, and Piazza del Velabro. These events were attended by large crowds, eager to witness the macabre rituals. Bugatti’s route to these sites, crossing the Ponte Sant’Angelo, gave rise to the saying “When Mastro Titta crosses the bridge,” indicating a scheduled execution.

His notoriety was such that he was forbidden from entering the city center for his own safety. The fear and loathing he inspired among the citizens of Rome were palpable, and his movements were restricted to ensure his protection. Despite his unpopularity, the public’s fascination with executions made him an essential, if unwelcome, figure in the social fabric of the time.

Personal Life and Public Perception

During the periods when he was not carrying out executions, Bugatti led a surprisingly mundane life, working as an umbrella seller in Rome. However, his day job did little to endear him to the public. His fellow citizens’ dislike and fear were so profound that he was restricted from visiting the city center for his own safety.

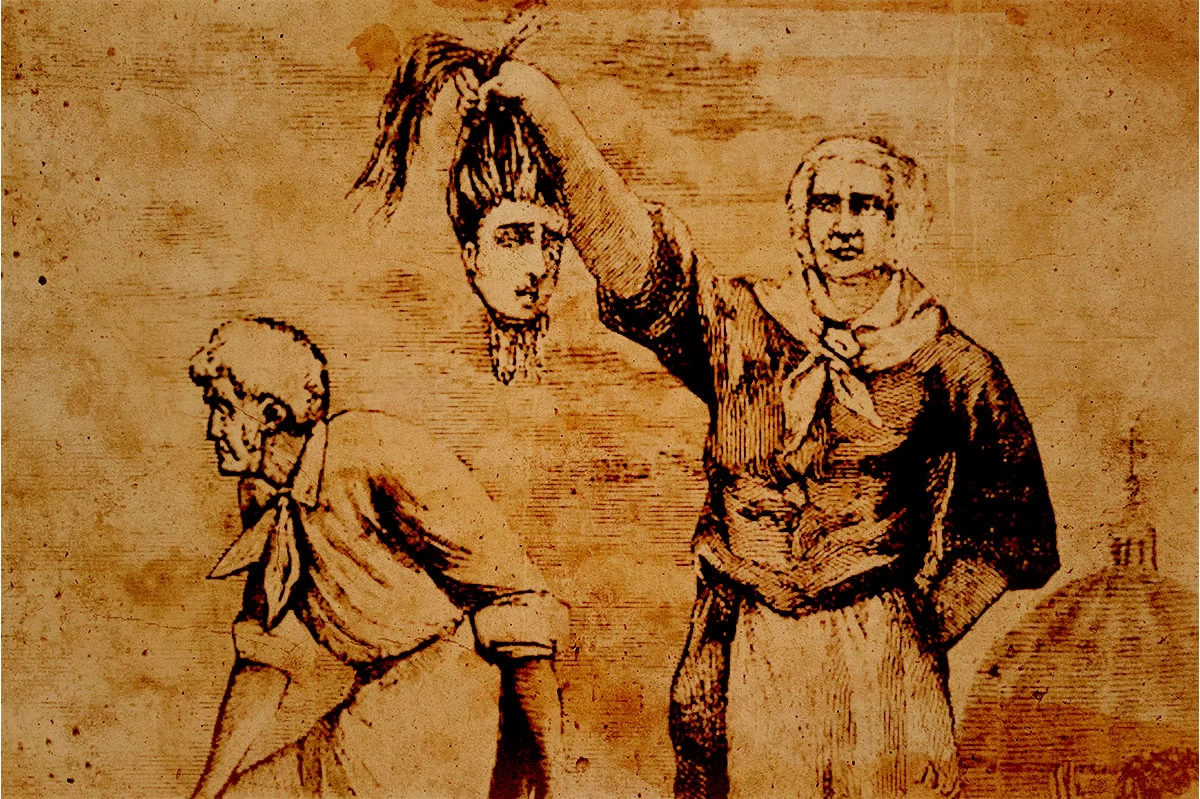

Public executions in Rome were more than just the carrying out of justice; they were a form of entertainment. People from all walks of life gathered to witness the final moments of the condemned. Bugatti, with his distinctive scarlet cloak, became a central figure in these grim spectacles, further embedding himself in the collective consciousness of the time.

Historical Witness Accounts

The execution methods and the atmosphere of these events were documented by several historical figures. The poet George Gordon Byron, for instance, provided a vivid description of an execution he witnessed in Piazza del Popolo in a letter to his publisher. His account captures the intense emotions and the gruesome reality of Bugatti’s work.

Similarly, the English writer Charles Dickens, during his visit to Rome, witnessed an execution carried out by Bugatti and recounted the event in his book “Letters from Italy.” These firsthand accounts offer invaluable insights into the period and the societal attitudes towards capital punishment.

Cultural Impact

Mastro Titta’s influence extended beyond his lifetime, impacting literature and popular culture. His nickname became synonymous with executioners in Rome, a testament to his infamy. The scarlet cloak he wore during executions is preserved in the Criminology Museum of Rome, serving as a tangible reminder of his chilling legacy.

In 1891, a book titled “Mastro Titta, the executioner of Rome: memoirs of an executioner written by himself” was published. Although a false autobiography, it was inspired by the notebook Bugatti kept, chronicling his executions. Additionally, the poet Giuseppe Gioachino Belli dedicated several sonnets to Mastro Titta, including one that describes the hanging of Antonio Carmadella. These literary works highlight the deep impression Bugatti left on those who lived through his era.

The poet Giuseppe Gioachino Belli dedicated several sonnets to Mastro Titta. In particular, no. 68, composed in 1830, describes the hanging of Antonio Carmadella, guilty of the murder of the canon and partner in crime Donato Morgigni. The hanging was carried out in 1749, well before Bugatti was born, but the executioner is still called Mastro Titta, as Bugatti was so famous.

The day they hanged Camardella

I had just been confirmed.

It seems to me now that my godfather took me to the market

I bought myself a top and a sweet roll.

My father then took the buggy

But first he wanted to enjoy the hanging:

He lifted me up high

Saying, “See how beautiful the gallows!”

Suddenly Mastro Titta struck the condemned

A kick in the rear, my father struck me

A slap to the right cheek.

“Take it,” he said, “and remember well

That this same fate is destined

A thousand others who are better than you.

Conclusion

Giovanni Battista Bugatti, or Mastro Titta, remains a fascinating yet macabre figure in history. His life as an executioner for the Papal States provides a stark glimpse into a period where public executions were both a form of justice and a spectacle. Through artifacts, literature, and historical accounts, the legacy of Mastro Titta continues to be remembered, offering an enduring reminder of the darker aspects of human history.