In the ancient city of Avaris, now known as Tell el-Daba, a remarkable archaeological discovery has shed light on a peculiar and disturbing practice that was once a part of the region’s rich history. A team of archaeologists from the Austrian Archaeological Institute and the Austrian Academy of Sciences have unearthed the skeletal remains of 16 right hands, buried beneath the foundations of an ancient palace, dating back approximately 3,600 years. This startling find not only reveals the grim realities of warfare and power dynamics in the Hyksos-ruled Egypt but also raises intriguing questions about the cultural and religious significance of this macabre ritual.

The Discovery of the Severed Hands

The archaeological excavations conducted at Tell el-Daba, the capital of the Hyksos kingdom, have uncovered a startling discovery. Two pits were found in the forecourt of the ancient palace, containing a total of 14 severed right hands. Additionally, two more pits, each with a single hand, were discovered under a four-columned building, which appears to have served a ceremonial or religious purpose. These hands, dated to the time when the Hyksos King Khayan ruled from Avaris, provide a tangible glimpse into the brutal realities of that era.

The Hyksos’ Practice of Severed Hands

The discovery of these severed hands has shed light on a practice that was likely a common occurrence during the Hyksos’ reign. The hands are believed to have belonged to soldiers, either Egyptian or from the Levant region, who were captured and killed in battle. The practice of removing the right hand of fallen enemies was a way for the victorious warriors to tally their kills and present them to the king or a representative official in exchange for “gold of valor.”

This gruesome ritual served not only a practical purpose but also held symbolic and religious significance. By removing the right hand, the warrior’s strength and ability to wield a weapon were permanently crippled, leaving him defenseless in the afterlife. This act was seen as a way to subjugate and diminish the enemy, both in the physical world and the spiritual realm.

The Tomb Inscription of Soldier Ahmose

While the discovery of the severed hands provides physical evidence of this practice, the biographical inscription on the tomb of the soldier Ahmose offers a first-hand account of the ritual. Ahmose, who fought under the Pharaohs Ahmose I, Amenhotep I, and Thutmose I, recounts his experiences in securing the “gold of valor” by presenting the severed hands of his fallen enemies.

Ahmose’s inscription reveals the extent to which this practice was ingrained in the military culture of the time. He proudly describes his exploits in battles against the Hyksos, the Mitanni, and rebellious Nubians, and the subsequent rewards he received for the severed hands he brought back as trophies.

The Continuity of the Severed Hand Ritual

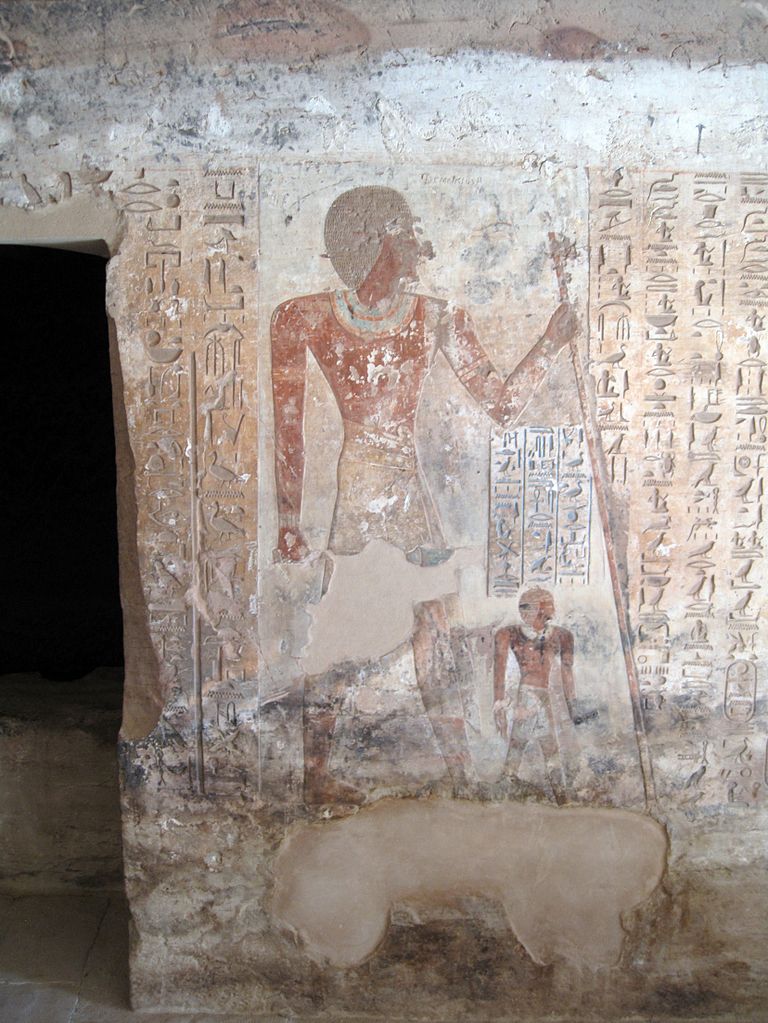

The practice of collecting severed hands as war trophies did not end with the Hyksos rule. Centuries later, during the reign of Rameses III, massive reliefs on the outer pylons of his mortuary temple at Medinet Habu depict officials meticulously counting and presenting baskets full of severed hands to the pharaoh, a testament to the enduring nature of this macabre ritual.

Conclusion

The discovery of the 16 severed right hands in the ancient city of Avaris has shone a spotlight on a disturbing yet fascinating aspect of Egypt’s past. This grim ritual, which spanned centuries and involved the capture, mutilation, and ritual burial of fallen enemies, provides a chilling glimpse into the brutal realities of warfare and the complex power dynamics that shaped the region during the Hyksos’ reign. As archaeologists and historians continue to unravel the mysteries of this ancient practice, it serves as a sobering reminder of the extremes to which human conflict can escalate, and the enduring influence of cultural and religious beliefs on the conduct of war.