In the remote hinterlands of southern Siberia, Russian archaeologists have recently made a remarkable discovery that could rewrite the history of the region. During excavations as part of a railway expansion project, they uncovered a perfectly preserved grave containing the skeletal remains of an ancient charioteer, a horse-drawn carriage driver from around 1,000 BC. This finding is extraordinarily significant, as it challenges the existing understanding of when chariots were first used in this part of Asia.

The Charioteer’s Grave

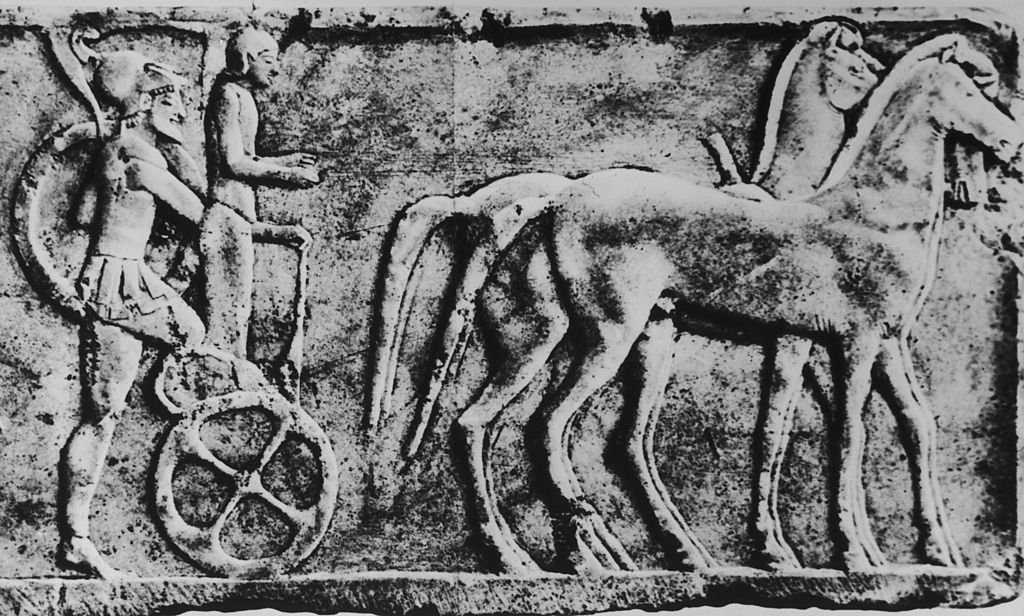

Working under the authority of the Siberian branch of Russia’s Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, the archaeologists were digging in the southern Siberian republic of Khakassia when they unearthed the charioteer’s burial site. The skeleton inside the grave was found intact, and a curious object was discovered laying across the body’s waist area – a long metal rod with curved hooks on each end. This device was actually designed to be attached to a charioteer’s belt, allowing them to wrap the reins around the belt to control the horses pulling the chariot.

This type of artifact has been found before at other archaeological sites in Russian territory, but its unusual shape initially puzzled the researchers. It wasn’t until they made comparisons with chariots and charioteer equipment discovered in Mongolia and China that the purpose of the hooked metal rod became clear. These recent findings from neighboring regions have revealed that such items were an essential accessory used by ancient chariot drivers.

Rewriting Siberian History

The discovery of the well-preserved charioteer’s grave in Siberia provides definitive evidence that horse-drawn chariots were used in the region as early as 3,000 years ago. This is a significant revision of the previous understanding, as archaeologists and historians had not believed chariots were being utilized in this part of Asia that long ago.

Various clues suggest the charioteer belonged to the Lugav culture, a Bronze Age people who were cattle breeders and also owned horses they could use to pull carriages or chariots. The grave itself was a relatively elaborate affair, built in a square shape, lined with stone, and covered by a protective earthen mound, reflecting the high regard in which the Lugav people held their charioteers.

Insights into Ancient Siberia

As the archaeological project in Khakassia has progressed, the Russian team has uncovered sites and artifacts linked to three distinct Bronze Age civilizations – the Karasuk, Lugav, and Tagar cultures. These findings paint a picture of a dynamic region where populations moved in and out and demographics changed over time, likely driven in part by ancient trade networks.

Horse-drawn chariots would have played a significant role in this mobility and exploration, dramatically expanding the distances people could travel. Chariots may have also been used in warfare between neighboring groups. The railway expansion project will continue to provide the archaeologists with opportunities to uncover more sites and artifacts that can further deepen our understanding of life in Siberia thousands of years ago.

Conclusion

The discovery of the exceptionally well-preserved 3,000-year-old grave of a Siberian charioteer is a remarkable archaeological find that challenges our existing knowledge of the region’s history. This discovery not only provides definitive evidence of the early use of chariots in the area but also offers insights into the culture, trade, and mobility of the Bronze Age populations that inhabited this remote part of the world. As the archaeological work continues, the potential to uncover even more secrets of ancient Siberia remains high, promising to rewrite the history of this intriguing and understudied region.