Many are familiar with the story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin, a tale of a mysterious figure who lured the children of a town away, never to be seen again. However, few realize that this story is based on real events, which over the years evolved into a fairy tale made to scare children. The true origins of this story are shrouded in mystery, with numerous theories attempting to explain what actually happened in the town of Hamelin in 1284.

The Pied Piper of Hamelin Story

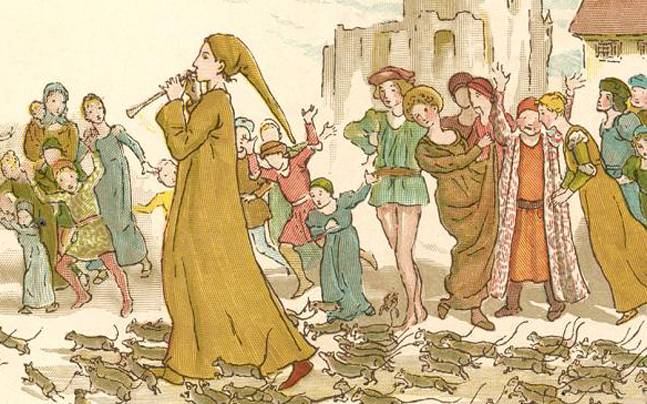

For those unfamiliar with the tale, the Pied Piper of Hamelin is set in 1284 in the town of Hamelin, Lower Saxony, Germany. This town was facing a rat infestation, and a piper, dressed in a coat of many colored, bright cloth, appeared. This piper promised to get rid of the rats in return for a payment, to which the townspeople agreed.

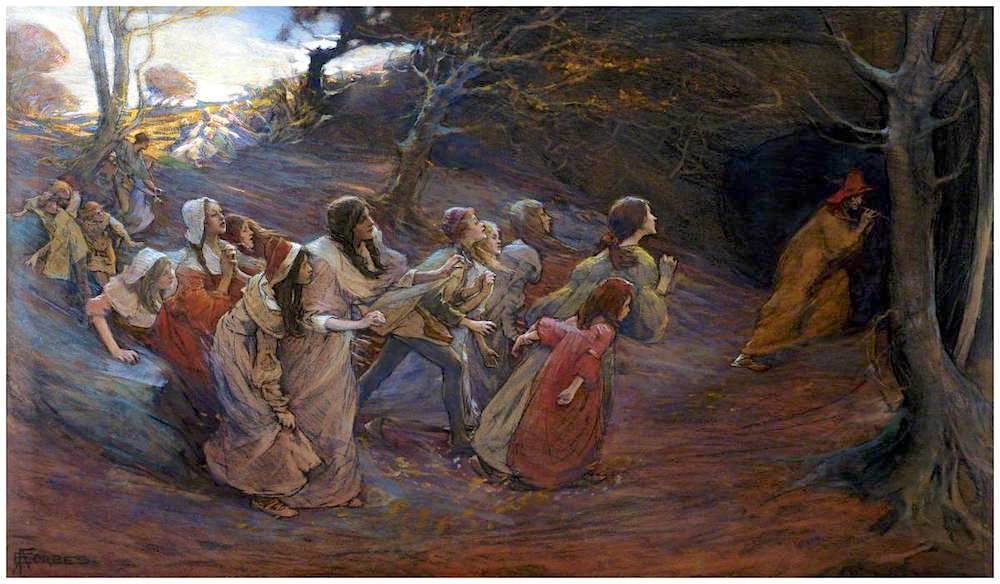

Although the piper got rid of the rats by leading them away with his music, the people of Hamelin reneged on their promise. The furious piper left, vowing revenge. On July 26 of that same year, the piper returned and led the children away, never to be seen again, just as he did the rats. Nevertheless, one or three children were left behind, depending on which version is being told. One of these children was lame, and could not keep up, another was deaf and could not hear the music, while the third one was blind and could not see where the other children were going.

The Record Shows No Rats

The earliest known record of this story is from the town of Hamelin itself. It is depicted in a stained glass window created for the church of Hamelin, which dates to around 1300 AD. Although it was destroyed in 1660, several written accounts have survived. The oldest comes from the Lueneburg manuscript (c 1440 – 50), which stated: “In the year of 1284, on the day of Saints John and Paul on June 26, by a piper, clothed in many kinds of colours, 130 children born in Hamelin were seduced, and lost at the place of execution near the koppen.” A 1384 entry in Hamelin’s town records also grimly states “It is 100 years since our children left.”

The supposed street where the children were last seen is today called Bungelosenstrasse (street without drums), as no one is allowed to play music or dance there. Incidentally, it is said that the rats were absent from earlier accounts, and only added to the story around the middle of the 16th century. Moreover, the stained glass window and other primary written sources do not speak of the plague of rats.

What Actually Happened in Hamelin?

If the children’s disappearance was not an act of revenge, then what was its cause for the Pied Piper’s actions? There have been numerous theories trying to explain what happened to the children of Hamelin.

One theory suggests that the children died of some natural causes, and that the Pied Piper was actually a personification of Death. By associating the rats with the Black Death, it has been suggested that the children were victims of that plague. Yet, the Black Death was most severe in Europe between 1348 and 1350, more than half a century after the event in Hamelin. Another theory suggests that the children were actually sent away by their parents, due to the extreme poverty in which they were living. Yet another theory speculates that the children were participants of a doomed ‘Children’s Crusade’, and might have ended up in modern day Romania.

There is also the suggestion that the departure of Hamelin’s children is tied to the Ostsiedlung, in which a number of Germans left their homes to colonize Eastern Europe. Reflecting on this hypothesis, Wibke Reimer, project coordinator at the Hameln Museum, says “In this scenario the Pied Piper played the role of a so-called locator or recruiter.

They were responsible for organising migrations to the east and were said to have worn colourful garments and played an instrument to attract the attention of possible settlers.” Yet another suggestion is that this is an account of dance mania, also known as St. Vitus’ Dance. This affliction gripped mainland Europe between the 14th and 17th centuries, and has been described as individuals dancing “hysterically through the streets for hours, days, and apparently even months, until they collapsed due to exhaustion or died from heart attack or stroke.”

Another of the darker theories even proposes that the so-called Pied Piper was actually a paedophile who crept into the town of Hamelin to abduct children during their sleep. Perhaps the horrible nature of the children’s disappearance is the reason why there are few details on what happened. Reimer ponders “Did something happen that officials had been covering up? Something so traumatic that it was transmitted orally for so long in the town’s collective memory, over decades and even centuries?”

Historical records suggest that the story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin was a real event that took place. This could stoke real fear in parent’s hearts – worrying whispers that a number of real children have been lost to some frightening unknown force. The transmission of this story undoubtedly evolved and changed over the centuries, although to what extent is uncertain. The mystery of what really happened to those children has never been solved. The story also raises the question, if the Pied Piper of Hamelin was based on reality, how much truth is there in other fairy tales that we were told as children?