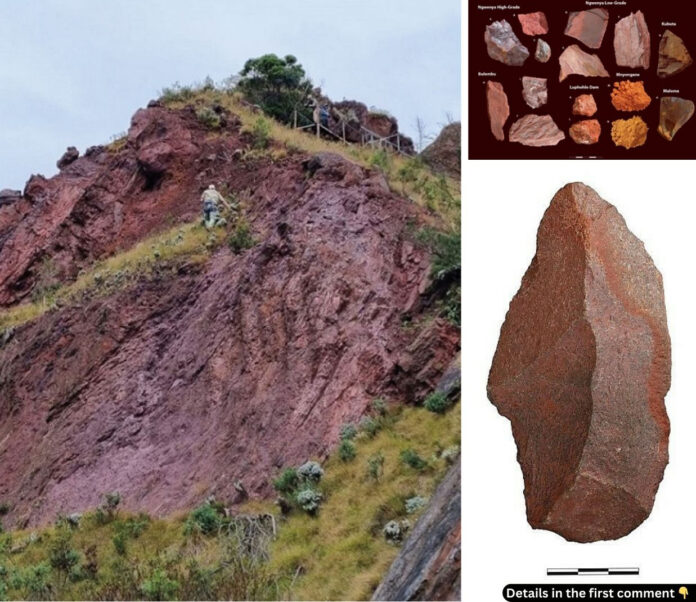

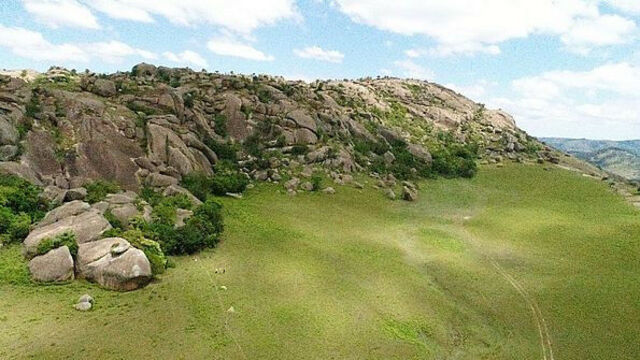

Nestled high on Bomvu Ridge in Eswatini, Lion Cavern stands as the world’s oldest known ochre mine, dating back an astounding 48,000 years. This archaeological wonder reveals humanity’s earliest efforts to extract and utilize ochre—a vibrant earth mineral that served as both a tool for survival and a symbol of cultural expression. Its discovery not only underscores the pivotal role of southern Africa in human evolution but also offers a window into the technological advancements and social systems of early human societies.

The Historical and Cultural Significance of Ochre

Ochre’s Symbolic Role

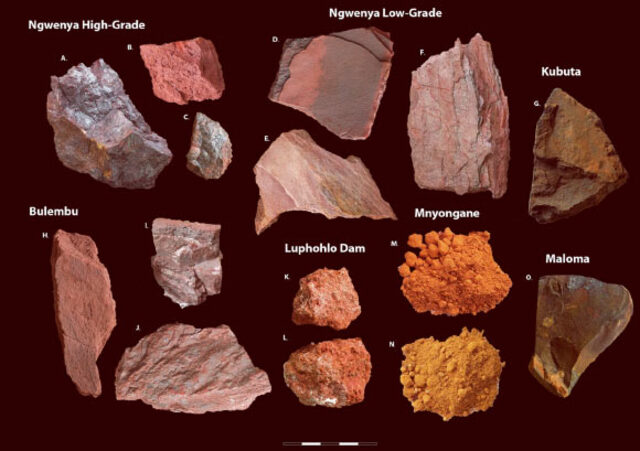

Ochre, often red, yellow, or violet, has been a cornerstone of human culture for millennia. Early humans used it in ritualistic contexts, adorning themselves for ceremonies and burials. As an essential element of symbolic art, ochre allowed communities to express identity, spirituality, and social bonds. Its presence in ancient rock art, such as the San paintings found near Lion Cavern, speaks to its profound cultural resonance.

Practical Applications

Beyond its symbolic importance, ochre had practical applications that showcase the ingenuity of early humans. By combining ochre with organic materials like animal fat, milk, and resin, they created long-lasting paints and adhesives. Its transport over vast distances further highlights the interconnectedness of early trade networks, emphasizing ochre’s value as a commodity.

Continuity Over Time

The cultural significance of ochre has endured into modern times, particularly in Eswatini. It remains a vital component of Swazi traditions, used in wedding ceremonies and healing rituals. For instance, Swazi brides are painted with a mixture of red ochre and animal fat to symbolize their new status in the community, bridging ancient practices with contemporary cultural expressions.

Video

Explore Africa’s Lion Cavern, home to the world’s oldest ochre mine, dated at 48,000 years old – watch the video to uncover the significance of this ancient site!

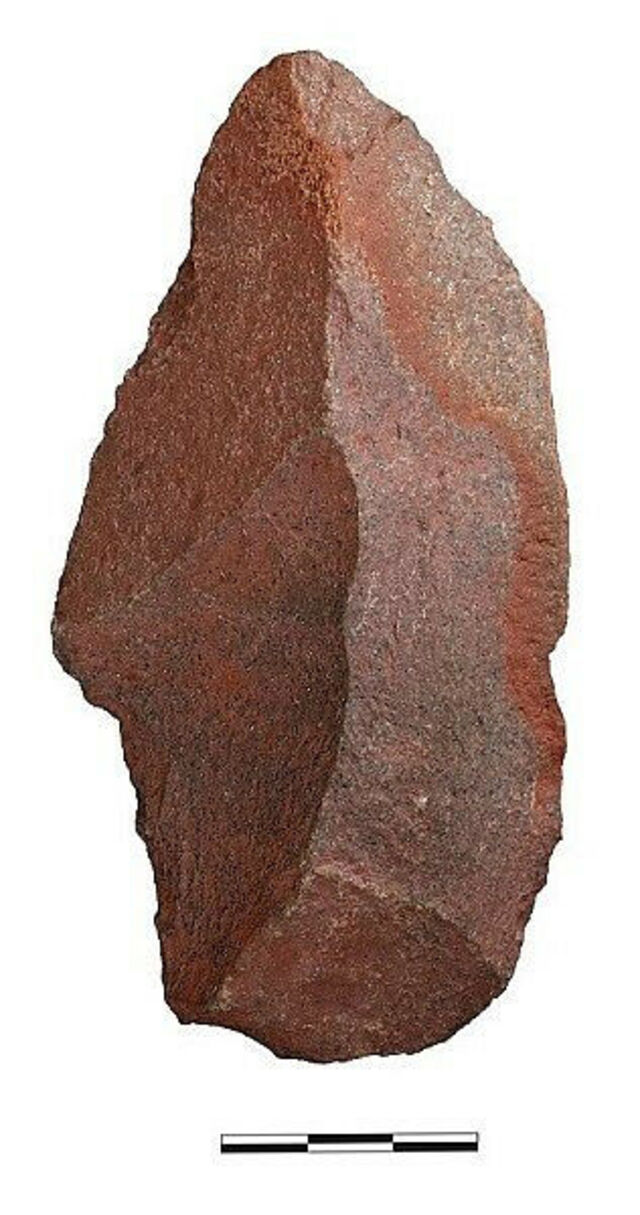

Discovery and Archaeological Insights

Lion Cavern, part of the Ngwenya Mine complex, is a testament to humanity’s first foray into large-scale mining. Archaeologists have uncovered tools like dolerite picks and hammerstones, evidence of early technological innovation. These tools were essential for extracting haematite—a form of red ochre—from the cavern’s rugged walls.

Modern dating techniques such as Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) have confirmed the mine’s astonishing age of 48,000 years. Spectroscopic studies have traced ochre from Lion Cavern to San rock art sites up to 20 kilometers away, proving its extensive distribution and significance in regional trade and culture.

The scale of mining at Lion Cavern marks a stark evolution from earlier, smaller ochre deposits found at sites like Blombos Cave in South Africa. While the Blombos discoveries revealed ochre used in limited quantities for symbolic purposes, Lion Cavern demonstrates organized, large-scale mining, reflecting an exponential growth in ochre’s importance to early human societies.

Lion Cavern’s Role in Early Human Society

The vast amounts of ochre extracted from Lion Cavern suggest its role as a valuable trade commodity. Long-distance trade networks likely emerged to distribute ochre across southern Africa, fostering social and economic connections among diverse hunter-gatherer groups.

The sophisticated mining techniques used at Lion Cavern point to the intergenerational transmission of knowledge. Early humans shared mining and ochre-processing methods, ensuring that these practices endured over time. Seasonal migrations and interactions between groups further facilitated the exchange of ideas, creating a network of cultural and technological learning.

Ochre’s ritualistic and symbolic uses were integral to early human society. By applying ochre in ceremonies, individuals and communities could express identity, beliefs, and social hierarchies. Its presence in burial sites and rock art underscores its role in shaping the cultural fabric of ancient societies.

Regional and Global Context

Lion Cavern’s significance is amplified when compared to other prehistoric ochre sites, such as Pinnacle Point and Blombos Cave in South Africa. While these sites highlight early symbolic uses of ochre, Lion Cavern stands out for its scale, complexity, and organized production, positioning it as a central hub of cultural and technological innovation.

The discoveries at Lion Cavern reinforce Eswatini’s role in the cultural and technological evolution of humankind. They also highlight shared traditions and innovations across Africa, emphasizing the continent’s pivotal contribution to the development of human culture.

Preservation and Future Research

The Lion Cavern site faces threats from past and present mining activities. Large-scale iron ore mining in the 20th century devastated much of the surrounding Ngwenya Mine complex, leaving Lion Cavern as one of the few surviving remnants. Preserving this site is crucial for safeguarding its historical and cultural significance.

Momentum is building to designate Lion Cavern as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Such recognition would not only protect the site but also draw global attention to its importance in understanding early human history.

Local researchers, including young Swazi scholars, are playing a vital role in advancing our understanding of Lion Cavern. Ongoing excavations and studies hold the promise of uncovering new insights into the lives of early humans and their use of ochre.

Conclusion

Lion Cavern is more than just the world’s oldest ochre mine—it is a testament to early human ingenuity, culture, and innovation. From its role in symbolic rituals to its influence on trade and social networks, ochre was a cornerstone of early human life. Preserving Lion Cavern and recognizing it as a global heritage site is essential to ensuring that its legacy endures for future generations. This extraordinary site reminds us of the shared history that unites humanity and the profound cultural advancements that began in the heart of Africa.