Nestled in the quiet corners of churches across Germany, Austria, and Switzerland lie extraordinary relics that combine the sacred and the macabre. These are Europe’s jeweled skeletons—Christian martyrs from the Roman catacombs, transformed into dazzling displays of devotion. Hidden from view for centuries, these relics have been resurrected in modern times thanks to the work of photographer and author Paul Koudounaris, whose book Heavenly Bodies brings their stunning legacy back into the light.

Uncovering the Origins: From Catacombs to Cathedrals

The story of these skeletal treasures begins in 1578, when catacombs beneath Rome were discovered, revealing hundreds of skeletons believed to belong to early Christian martyrs. These relics became an essential resource for the Catholic Church, which had lost many of its saintly relics during the Protestant Reformation. Sent to churches throughout Europe, the skeletons were reimagined as sacred martyrs, despite their unknown identities. For many congregations, these relics symbolized a tangible connection to the divine and served to reinforce Catholic faith during a turbulent time.

The Art of Adornment: Transforming Bones into Treasures

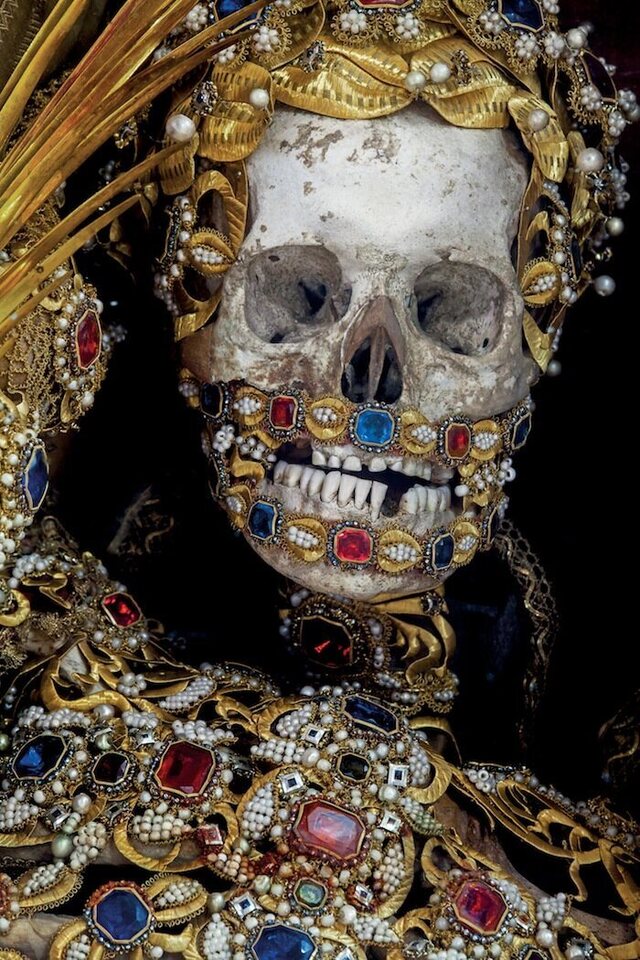

What sets these skeletons apart is the intricate artistry that transformed them into jeweled masterpieces. Churches spent years decorating the bones with gold, gemstones, and fine fabrics. Entire skeletons were adorned with elaborate crowns, robes, and even eye sockets filled with jewels. Craftsmen used fine wirework, silk mesh, and precious metals to create a sense of reverence and awe.

For instance, the skull of St. Getreu, located in Ursberg, Germany, is encased in silk and decorated with gemstones, showcasing the skill of German artisans. Meanwhile, St. Valentin in Bad Schussenreid features an intricately adorned hand, reflecting the same level of devotion and artistry. These skeletons were not merely relics; they were artistic triumphs, merging faith with craftsmanship.

Video

Discover the stunning jeweled skeletons of Catholic saints – watch the video to learn about these beautifully adorned relics and their significance in religious history!

A Shift in Perception: The Enlightenment and Decline

By the 18th century, the jeweled skeletons became symbols of excess in the age of the Enlightenment. As rationalism and skepticism grew, these extravagant displays of wealth and faith were seen as embarrassing relics of a bygone era. Many of the skeletons were hidden away or dismantled, their elaborate decorations stripped or lost. Churches that once revered these relics began to see them as awkward reminders of indulgence rather than objects of veneration.

Despite this decline in their prominence, some skeletons survived intact, tucked away in church vaults and forgotten by time. It wasn’t until Paul Koudounaris began his work in the 21st century that their beauty and significance were rediscovered.

Notable Examples: A Journey Through Europe’s Relics

Koudounaris’ research unearthed numerous examples of these jeweled skeletons, each with its unique story and adornments. Among them is St. Munditia, housed in St. Peter’s Church in Munich. Clutching a flask said to contain her blood, St. Munditia’s skeleton was hidden for decades before being rediscovered. Her jeweled figure now stands as a testament to the devotion of those who prepared her for eternal rest.

In Austria, St. Vincentus lies in Stams Abbey, his ribs exposed beneath golden leaves and his hand raised in a gesture of modesty. His intricate adornments symbolize both humility and divine glory. Similarly, St. Albertus, whose remains arrived at St. George’s Church in Germany in 1723, became a source of wonder for parishioners, offering a tangible link to the early Christian martyrs.

Other examples include St. Deodatus, whose skull in Switzerland was reconstructed with wax and fabric, and St. Luciana, displayed in Heiligkreuztal, Germany, with ornate details prepared by local nuns.

A Modern Revival: The Work of Paul Koudounaris

Paul Koudounaris’ book Heavenly Bodies has played a pivotal role in reviving interest in these skeletal relics. His photography captures their intricate beauty, highlighting the craftsmanship and devotion that went into their creation. Through his work, Koudounaris has reintroduced these relics as not just objects of religious significance but also as historical artifacts that bridge the gap between art and faith.

Koudounaris’ research also sheds light on the cultural and historical context of these skeletons. They represent a period when the Catholic Church sought to assert its authority and inspire awe through material splendor. Yet, they also reveal a deeply human desire to honor the dead and create a tangible connection to the divine.

Cultural and Historical Significance

The jeweled skeletons hold a dual significance: as religious relics and as artistic treasures. For the Catholic Church, they served as powerful symbols of faith and resilience in the face of Protestant challenges. The intricate decorations reflected the wealth and devotion of the churches that housed them, reinforcing their role as centers of worship and community.

From a historical perspective, these skeletons offer insight into the interplay between religion, art, and society during the Counter-Reformation. They stand as a testament to the lengths humans will go to honor their beliefs and create beauty, even in the face of mortality.

Conclusion: Timeless Elegance and Eternal Rest

Europe’s jeweled skeletons are more than just relics of the past; they are masterpieces that transcend time, blending faith, art, and history into a singular narrative. Thanks to the efforts of Paul Koudounaris, these extraordinary artifacts have been brought back into the public eye, allowing us to appreciate their beauty and significance.

While they may have been hidden or forgotten for centuries, the jeweled skeletons now stand as enduring reminders of humanity’s capacity for devotion and creativity. They invite us to reflect on the ways we honor the dead and celebrate the mysteries of life, death, and the divine.