The Valley of the Kings, a burial ground for Egypt’s most prominent rulers, is home to one of the most enigmatic discoveries in archaeology: the tomb KV55. Unearthed in 1907, this modest and unassuming tomb contained a single coffin with defaced inscriptions and a mysterious mummy that has puzzled scholars for over a century. Who was this individual, and why was their burial so desecrated? The answers remain elusive, but four compelling theories have emerged, each shedding light on the tumultuous Amarna period of ancient Egypt.

The Discovery of Tomb KV55

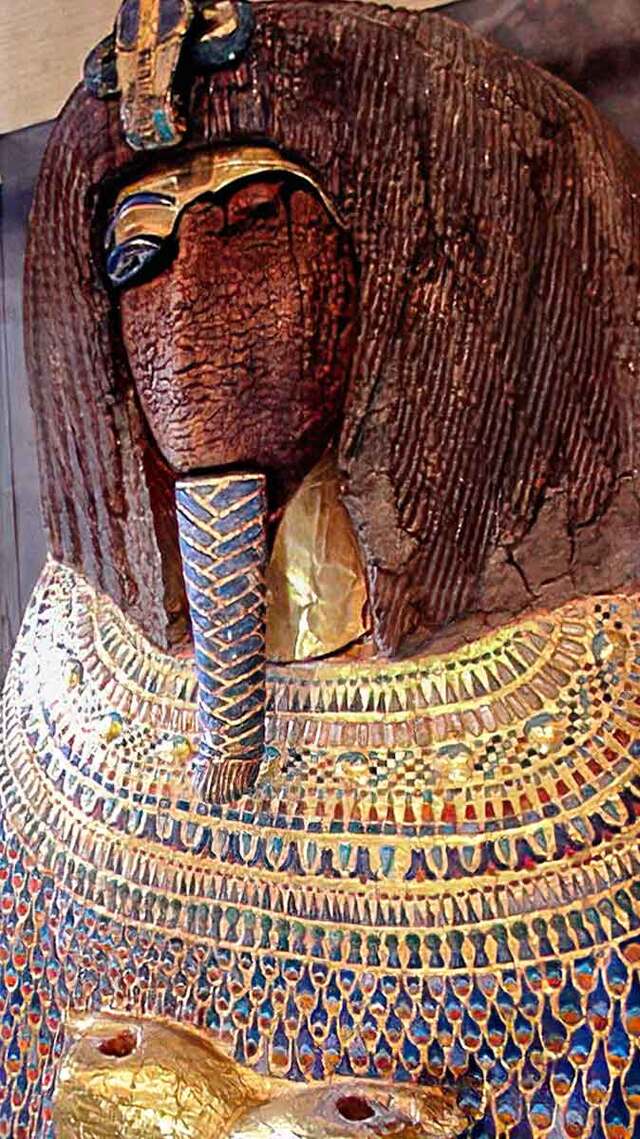

In January 1907, American archaeologist Theodore Davis and his team uncovered KV55 in the Valley of the Kings. Unlike the grand, elaborate tombs of other pharaohs, KV55 was small, undecorated, and damaged. Inside, the team discovered a chaotic scene: fragmented artifacts, defaced hieroglyphics, and a coffin missing its golden face.

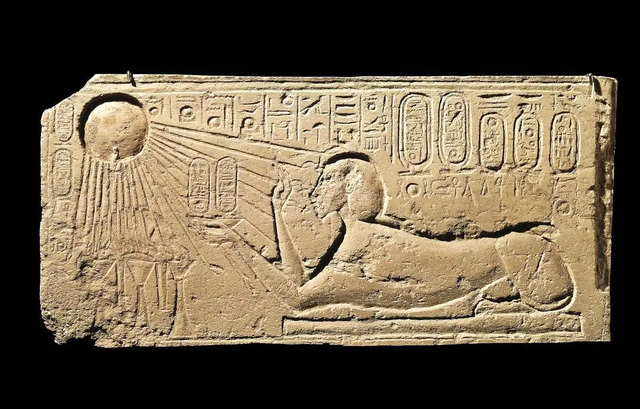

The tomb’s contents, however, offered tantalizing clues about its occupant and the period they lived in. Artifacts linked to the Amarna period—a time of religious upheaval under Pharaoh Akhenaten—were scattered throughout the chamber. These included Queen Tiye’s burial shrine, magical bricks bearing Akhenaten’s name, and canopic jars thought to depict Kiya, one of Akhenaten’s wives. Despite this wealth of items, the identity of the tomb’s occupant was far from clear. The coffin’s name had been scratched out, and the remains inside were too poorly preserved to provide definitive answers.

Video:

Theory 1: Queen Tiye

Queen Tiye, the Great Royal Wife of Amenhotep III and mother of Akhenaten, was initially thought to be the tomb’s occupant. Her name appeared on several artifacts, including her burial shrine, and the initial analysis of the mummy suggested it was female. This led Davis to confidently declare KV55 as the tomb of Tiye in his 1910 publication.

However, later discoveries disproved this theory. In 1898, another tomb, KV35, was found to contain the Elder Lady, a mummy later identified as Queen Tiye through DNA testing and matching artifacts. Tiye’s body, it seems, had been relocated multiple times before finally resting in KV35. While Tiye’s shrine was found in KV55, it is now believed that she was temporarily buried there alongside the unknown occupant before being moved again.

Theory 2: Kiya

Another candidate for KV55’s occupant is Kiya, a lesser-known wife of Akhenaten. Canopic jars depicting a woman with Kiya’s distinctive features were found in the tomb, and the coffin itself was originally designed for a woman. This led some scholars to suggest that Kiya was buried in KV55.

However, this theory also falters under scrutiny. The coffin shows signs of modification, such as the addition of a false beard and symbols associated with pharaohs, indicating it was repurposed for a male. Additionally, Kiya’s fall from favor during Akhenaten’s reign makes it unlikely she received such an honored burial. Most significantly, later studies confirmed that the KV55 mummy was male, ruling out Kiya as a candidate.

Theory 3: Akhenaten

Akhenaten, the heretic pharaoh who abandoned Egypt’s traditional gods in favor of the sun deity Aten, is a strong contender for the KV55 mummy. The tomb’s Amarna-period artifacts, including magical bricks inscribed with his name, support this theory. Moreover, Akhenaten’s controversial legacy explains the desecration of the tomb. Later Egyptians, seeking to erase the memory of his religious reforms, defaced his images and inscriptions wherever they appeared.

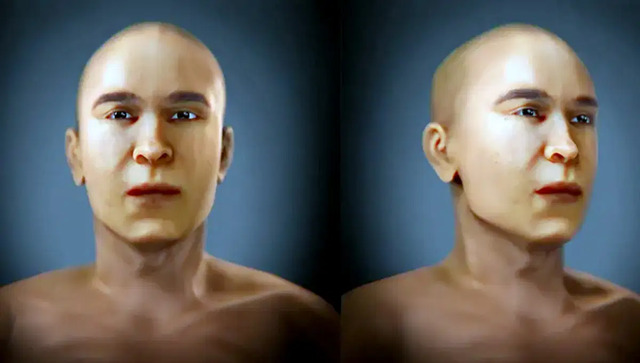

Historical accounts suggest that Akhenaten died at Amarna, his short-lived capital city, but his body may have been moved to KV55 by his son and successor, Tutankhamun. However, the age of the mummy presents a challenge to this theory. Studies have produced conflicting estimates, with some suggesting the individual was in their mid-30s, consistent with Akhenaten, while others argue the remains are of someone much younger.

Theory 4: Smenkhkare

Smenkhkare, a shadowy figure from the Amarna period, is another potential candidate. Believed to have been a co-regent or brief successor to Akhenaten, Smenkhkare’s life and death remain shrouded in mystery. His name does not appear on any artifacts in KV55, but the mismatched burial items suggest the tomb was hastily assembled, which aligns with the possibility of an unexpected death.

Supporters of this theory point to the mummy’s age, estimated by most studies to be in the early 20s. This aligns better with Smenkhkare than Akhenaten, who would have been in his 30s at the time of his death. Additionally, Smenkhkare’s connections to Akhenaten’s family and the Amarna period make him a plausible candidate for the tomb’s occupant.

The Challenges of Identifying KV55’s Mummy

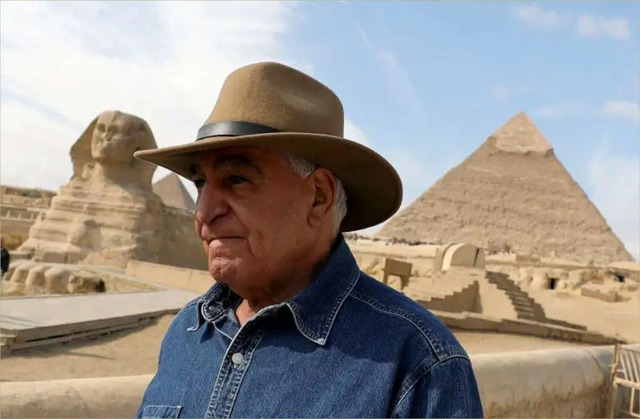

Despite over a century of research, the identity of KV55’s mummy remains uncertain. Conflicting age estimates, the poor preservation of the remains, and the lack of definitive inscriptions have all hindered efforts to solve the mystery. DNA studies, including a high-profile 2010 analysis led by Dr. Zahi Hawass, have added to the debate. While the study identified the KV55 mummy as the son of Amenhotep III and father of Tutankhamun, it did not conclusively determine whether the remains belonged to Akhenaten or Smenkhkare.

The Significance of KV55

Regardless of the mummy’s identity, KV55 offers invaluable insights into the tumultuous Amarna period. The tomb reflects the religious and political upheaval of the time, as well as the efforts of later Egyptians to erase this controversial chapter from their history. The desecration of the burial highlights the deep animosity toward Akhenaten and his legacy, while the presence of artifacts from multiple individuals underscores the complexities of royal burials in ancient Egypt.

Conclusion

The mystery of KV55 encapsulates the allure and frustration of archaeology. Was the tomb’s occupant Akhenaten, the radical pharaoh who upended Egypt’s traditions? Or was it Smenkhkare, his enigmatic co-regent or successor? While the evidence leans slightly toward Smenkhkare, definitive answers may never emerge. What is clear, however, is that KV55 remains a vital piece of the puzzle in understanding the Amarna period and its enduring impact on ancient Egyptian history.