In 1980, an enigmatic copper dome was pulled from the depths near the wreckage of the Santa Margarita, a Spanish treasure galleon lost in 1622. Initially mistaken for an oversized cooking cauldron, the artifact has sparked new excitement in maritime archaeology. Experts now propose that it may be the remains of a 17th-century primitive submarine, possibly one of the earliest diving bells ever discovered. If true, this find rewrites the history of maritime technology, unveiling the ingenuity of treasure hunters from centuries past.

A Remarkable Discovery

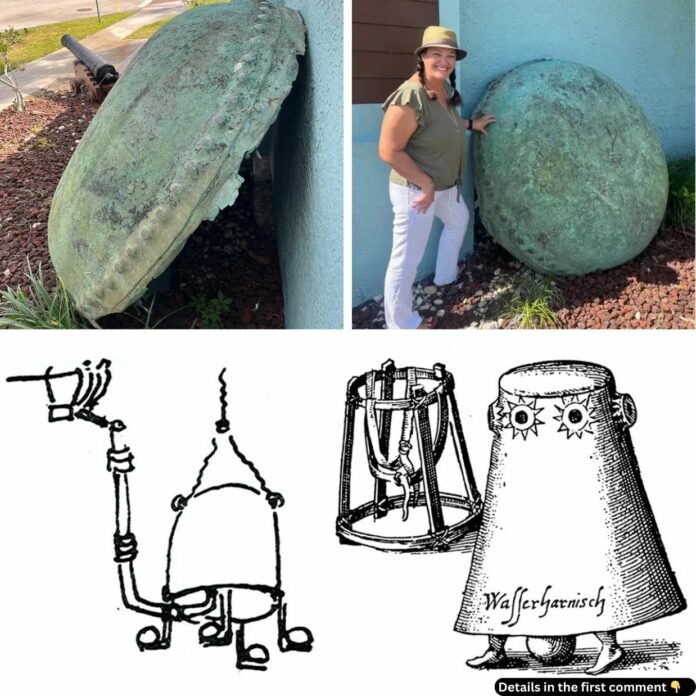

The copper dome, measuring 147 centimeters in diameter, was discovered just 40 miles west of Key West in the Florida Straits. It lay near the wreckage of the Santa Margarita, a Spanish treasure galleon that met its end during a hurricane. Over the years, the artifact became a centerpiece at the Mel Fisher Museum in Sebastian, Florida, where it intrigued visitors and archaeologists alike.

Though initially identified as a cooking vessel due to its size and shape, new theories began to emerge, challenging this simple explanation. The artifact’s robust construction and absence of charring or heating marks made it clear that it was no ordinary cauldron.

Video:

Diving into the Evidence

Maritime archaeologists Sean Kingsley and Jim Sinclair presented groundbreaking research in Wreckwatch Magazine, proposing that the copper dome was likely the upper section of an early diving bell. Diving bells, a revolutionary innovation of the time, were used to retrieve treasures from sunken ships. These devices provided a pocket of breathable air for divers, enabling them to work underwater for extended periods.

The dome’s features closely align with historical diving bell descriptions:

- Made from two copper sheets and reinforced with rivets for durability.

- No evidence of heat damage, which ruled out its use in cooking or other domestic purposes.

- Found near iron ingots, potentially used as anchors to secure the bell underwater.

The Santa Margarita Connection

The artifact’s proximity to the Santa Margarita adds weight to the diving bell hypothesis. The Santa Margarita was a treasure ship carrying immense wealth, including gold, silver, and cannons, when it sank in 1622. Historical records recount a successful salvage operation in the 17th century, led by Francisco Nuñez Melián, who recovered 350 silver ingots, thousands of gold coins, and cannons. Such an ambitious endeavor likely required advanced technology, like a diving bell, to access the wreckage at depth.

Though no specific mention of a diving bell exists in the records, the recovered treasure suggests that sophisticated methods were employed. The discovery of the copper dome may be the missing link that explains how such a massive haul was achieved.

Historical Context of Diving Bells

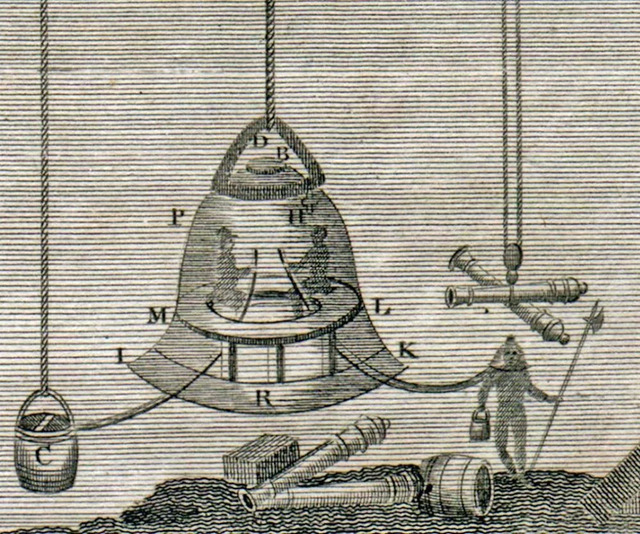

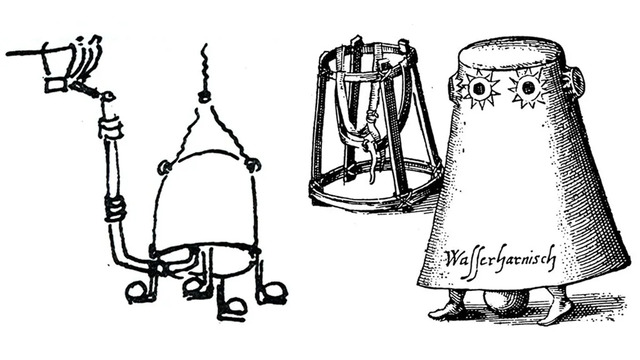

Diving bells were a remarkable technological innovation in the 17th century. Pioneered by figures like Jerónimo de Ayanz, who patented a design in 1606, these devices were used for pearl diving and treasure recovery. By creating an air pocket underwater, diving bells allowed divers to operate in previously inaccessible depths.

One notable example is the design by Edmond Halley, famous for Halley’s Comet, in 1690. Halley’s bell could accommodate multiple divers and included an air replenishment system, demonstrating the rapid advancements in underwater technology. The copper dome from the Santa Margarita may represent an earlier and more primitive version of this ingenious invention.

Analyzing the Artifact

The dome’s construction and design offer compelling evidence for its role as a diving bell. The robust rim, reinforced with rivets, suggests it was built to withstand underwater pressure. Maritime archaeologist Joseph Eliav noted that the seam between the dome and its base could reveal crucial details. If traces of caulking, sealing, or welding are found, it would strongly support the diving bell hypothesis.

The researchers also hypothesize that the dome was part of a larger apparatus. The lower section, likely made of wood and leather, would have deteriorated over time, leaving only the copper top. This design could have accommodated up to three divers, tethered to a surface vessel for air supply and stability.

Revolutionary Implications

If confirmed as a diving bell, this artifact would redefine our understanding of maritime innovation in the 17th century. It highlights the resourcefulness of treasure hunters, who adapted cutting-edge technology to recover valuable cargo from the ocean floor. The successful use of such devices underscores the advanced engineering and problem-solving skills of the time.

Moreover, the artifact provides a glimpse into the broader history of underwater exploration. It bridges the gap between early attempts at diving and the sophisticated technologies that followed, laying the groundwork for modern scuba diving and underwater salvage techniques.

Challenges and Future Research

While the diving bell hypothesis is compelling, further research is needed to confirm the artifact’s identity. Experts plan to conduct detailed analyses of the riveted seams and look for traces of sealing materials. Peer-reviewed studies will also evaluate the artifact’s construction and historical context.

Additionally, efforts are underway to explore the surrounding seabed for more clues. Finding additional components of the diving bell or related artifacts could provide definitive proof of its purpose and connection to the Santa Margarita.

Conclusion

The copper dome near the Santa Margarita wreckage is more than just a fascinating relic—it is a window into the ingenuity of 17th-century maritime pioneers. If indeed a diving bell, it represents a remarkable achievement in underwater exploration and treasure recovery. As researchers continue to unravel its secrets, this artifact promises to deepen our understanding of history, innovation, and the enduring human drive to conquer the unknown. The mystery of the seas lives on, inspiring both curiosity and admiration for the resourcefulness of those who came before us.