High in the mountains of Guatemala lies the small city of Chajul, a place where history whispers through the walls of humble adobe homes. In 2003, a farmer’s simple renovation revealed stunning murals hidden beneath layers of plaster, depicting vivid scenes of dancers, musicians, and floral motifs. These centuries-old artworks blend Spanish colonial and Maya traditions, offering a rare glimpse into a world where cultures collided and fused. This discovery has since sparked global fascination, turning Chajul into a living archive of resilience and artistic brilliance.

The Accidental Discovery of Chajul’s Murals

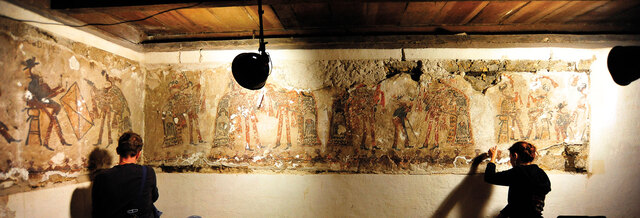

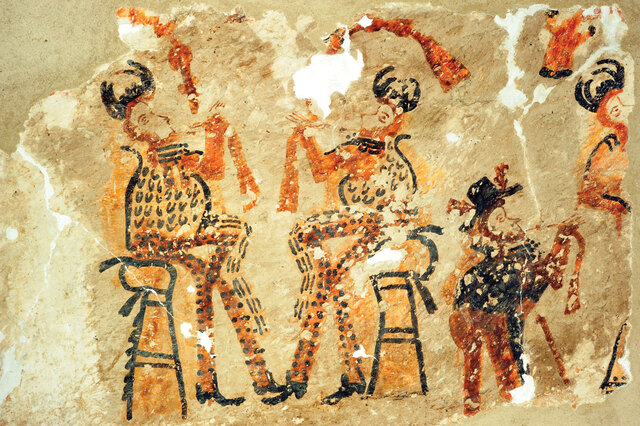

The murals in Chajul came to light thanks to a local farmer named Asicona, who uncovered them in an astonishingly accidental way. While renovating his modest home, he removed layers of plaster from his walls, only to reveal intricate depictions of musicians, dancers, and floral motifs hidden beneath. Spanning three walls of a single room, the paintings featured figures dressed in a hybrid of Spanish and Maya attire, telling a story of cultural fusion. Among the vivid imagery were a dwarf carrying a stick, musicians playing flutes and drums, and dancers adorned in elaborate costumes, creating a visual narrative that was as striking as it was enigmatic.

Though local authorities were informed, detailed research did not commence until 2015, when a team led by archaeologist Jarosław Źrałka from Jagiellonian University began studying and conserving the murals. To their amazement, the paintings were layered, with the earliest dating back to the seventeenth or eighteenth century. The discovery was not an isolated case, as similar murals were found in eight other homes, further enriching the story of Chajul’s unique cultural legacy.

Video:

A Kaleidoscope of Artistic Elements

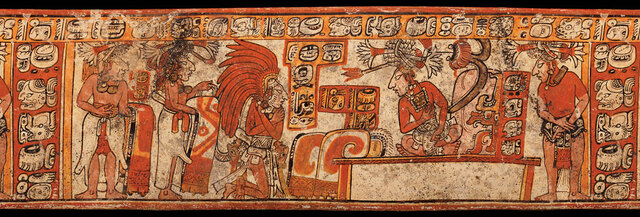

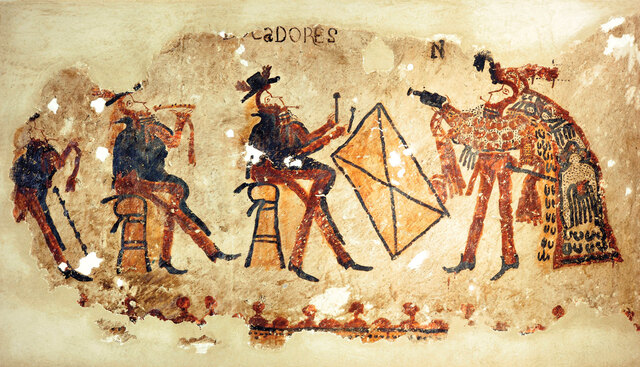

The murals in Chajul stand out for their intricate details and the way they merge Spanish and Indigenous elements. Musicians depicted in the paintings play chirimías, an oboe-like instrument introduced by the Spanish, and rectangular drums. They are dressed in Spanish-style attire, complete with heeled shoes, puffed sleeves, and broad-brimmed hats.

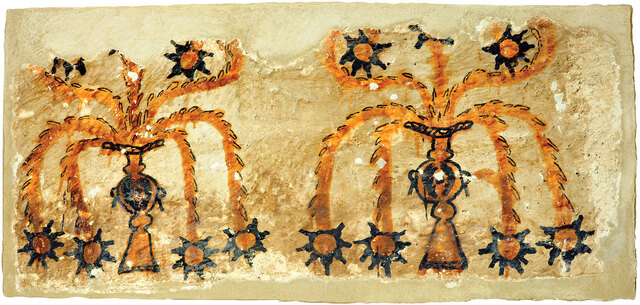

In contrast, the dancers wear costumes that reflect both worlds. Their headdresses, feathered cloaks, and jaguar-pelt trousers hark back to pre-Hispanic Maya traditions, while their trousers and shoes reflect European styles. The paintings also feature symbolic vases with flowering plants, hinting at deeper spiritual or ritualistic meanings.

The use of pigments further underscores the connection to pre-colonial artistry. Analysis of the murals’ colors revealed similarities to those used in Maya art before the Spanish arrived, indicating that these works were created by Indigenous artists even as they adapted to the colonial context.

Chajul: A Historical and Cultural Crossroads

Chajul’s history stretches back to the Maya Late Classic period (A.D. 600–800), when it served as an important political center with its own dynasty of rulers. By the early sixteenth century, however, the Ixil Maya, including the inhabitants of Chajul, were subjugated by the Spanish. The colonizers forced the Ixil population from surrounding villages into Chajul, concentrating them into a single, more manageable community.

Despite the Spanish conquest, the Ixil retained elements of their traditional culture, blending them with imposed Christian practices. The rugged terrain and relative isolation of the region played a role in preserving these traditions. Dominican missionaries established cofradías, or brotherhoods, to encourage Catholic worship, but the Ixil adapted these organizations to include their Indigenous rituals and beliefs.

The Role of Cofradías and Ritual Dance Plays

The cofradías became pivotal in maintaining Chajul’s cultural identity. Each brotherhood cared for a specific Catholic saint, incorporating Indigenous rituals into their worship. The murals in Chajul are believed to depict elaborate dance plays organized by the cofradías. These performances were central to community life, involving extensive preparation and culminating in vibrant public celebrations.

The dance plays often portrayed narratives blending Christian and Maya elements. For example, the Baile de la Conquista, or Dance of the Conquest, dramatized the Spanish invasion of Guatemala while incorporating traditional Maya characters and themes. Another dance, the Tz’unun, or Hummingbird Dance, celebrated creation myths and featured women as central characters. Researchers believe the murals in Chajul may depict one or more of these performances, bringing long-lost traditions vividly to life.

Layers of Murals: A Testament to Cultural Continuity

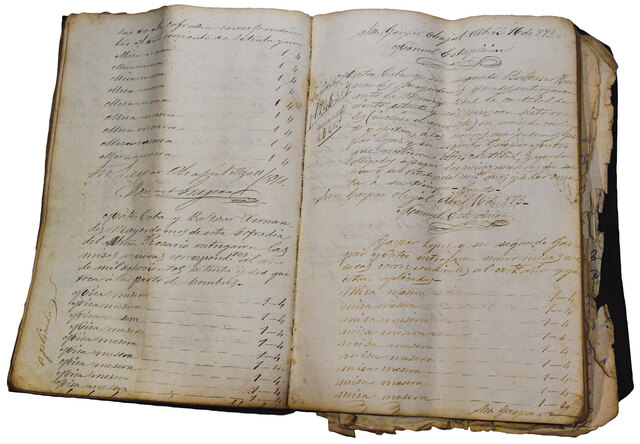

One of the most striking aspects of Chajul’s murals is the layering of paintings, with each layer representing a different period of the cofradías’ history. When a new mayordomo, or leader, took charge of a brotherhood, their home became the center of cofradía activities. This often involved repainting the walls with new murals, symbolizing the continuity of cultural traditions across generations.

In Asicona’s home, the murals’ layers reveal the evolving artistic styles and ritual practices of the Ixil over centuries. The scenes of dancers, musicians, and symbolic elements remained consistent, underscoring the enduring importance of these rituals in the community’s identity.

The Tz’unun: A Creation Story in Dance

Among the many dance plays performed in Chajul, the Tz’unun holds a special place. This celebration tells the story of Marikita, a weaver whose creations give rise to elements of the natural world, and Rey Oyeb’ Achi, her suitor who appears as a hummingbird. The narrative intertwines themes of love, creation, and transformation, connecting the characters to sacred Maya landscapes and Catholic saints.

The murals’ depictions of birds, flowers, and dancers wearing feathered cloaks suggest a link to the Tz’unun. Though this dance has not been performed regularly for decades, it remains a cherished part of Chajul’s oral tradition, with residents recounting its story as an integral part of their history.

Preserving the Murals and Their Legacy

The conservation of Chajul’s murals presents significant challenges, as they are located in private homes and exposed to the elements. Researchers have employed advanced techniques to stabilize and restore the paintings, ensuring their survival for future generations.

Beyond their artistic and historical value, the murals offer profound insights into the resilience of the Ixil people. They stand as a testament to the community’s ability to adapt and preserve their identity in the face of colonization, blending Indigenous and Christian traditions into a unique cultural tapestry.

Conclusion

The murals of Chajul are more than just stunning works of art—they are windows into a world where two cultures collided and intertwined. They reveal the creative ways in which the Ixil Maya navigated the challenges of colonialism, preserving their traditions while adopting new elements.

As researchers continue to study and conserve these paintings, they ensure that Chajul’s rich heritage remains a source of inspiration and pride for generations to come. Through these vibrant murals, the dancing days of the Maya live on, connecting the past to the present in a celebration of resilience and cultural fusion.