Vanilla, often associated with sweetness and indulgence, carries a history that is both bittersweet and extraordinary. Behind this globally cherished flavor lies the story of Edmond Albius, a 12-year-old enslaved boy from Réunion Island, whose groundbreaking discovery in 1841 transformed the cultivation of vanilla and revolutionized the global spice industry. Despite the monumental impact of his work, Edmond’s story remains one of resilience, innovation, and injustice—a reminder of the unrecognized contributions of the oppressed.

Edmond Albius: A Boy with a Vision

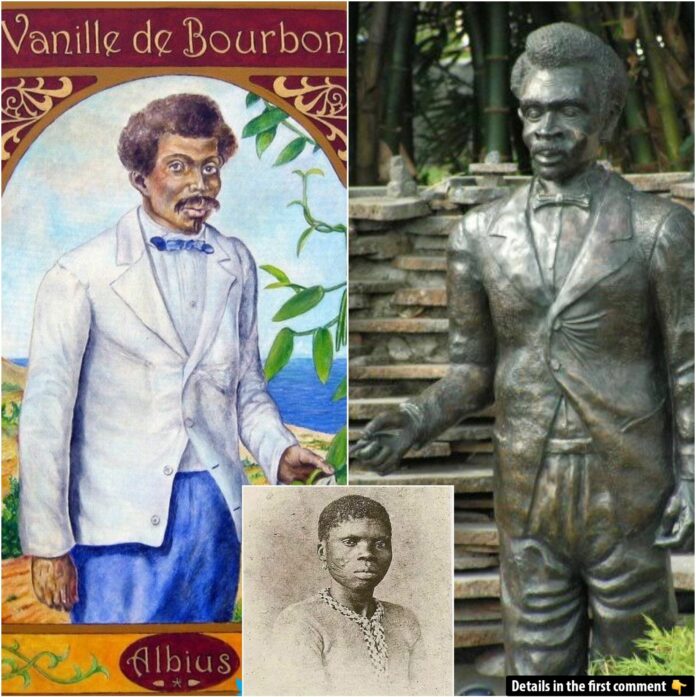

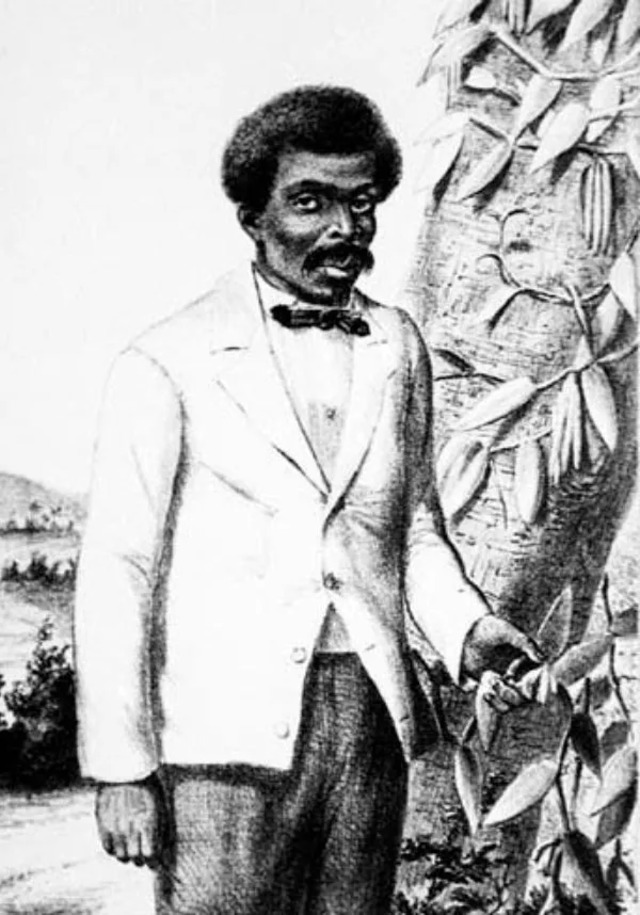

Edmond Albius was born into slavery in 1829 on Île de Bourbon, now known as Réunion Island. Orphaned at birth, with his mother dying during childbirth and his father absent, Edmond was raised on a plantation under the care of Ferréol Bellier-Beaumont. Unlike many enslaved individuals, Edmond had the unique opportunity to learn about botany and horticulture from his master, sparking a lifelong curiosity.

By the age of 12, Edmond made a discovery that would change the course of agricultural history. Using a simple tool like a toothpick, he devised a method to hand-pollinate the vanilla orchid—a plant notoriously difficult to cultivate outside its native Mexico due to its reliance on a specific species of bee. Edmond’s technique involved manually lifting the flower’s membrane and combining the male and female parts, a process that could be completed in seconds. This method, now known as “marriage” or le geste d’Edmond in French, allowed vanilla cultivation to expand beyond Mexico, opening doors to global production.

Video:

The Global Impact of Edmond’s Discovery

Before Edmond’s breakthrough, the vanilla orchid’s dependency on the Melipona bee confined its cultivation to Mexico. Attempts to grow vanilla in other regions failed because artificial pollination methods were either unknown or ineffective. Edmond’s simple yet ingenious solution unlocked the potential for large-scale vanilla farming.

A Vanilla Boom on Réunion Island

Thanks to Edmond’s pollination method, Réunion Island and other French colonies rapidly overtook Mexico as the world’s leading producers of vanilla. By 1867, Réunion exported 20 tons of vanilla beans annually, a figure that would grow to 200 tons by the end of the 19th century. This booming industry transformed the island’s economy and cemented vanilla’s place as one of the world’s most valuable spices.

A Lasting Legacy

Today, Edmond’s pollination technique is still used worldwide. Whether in Madagascar, Indonesia, or Mexico, every vanilla bean owes its existence to the method discovered by an enslaved boy nearly two centuries ago. Vanilla has become the second most expensive spice globally, after saffron, and is integral to industries ranging from food and cosmetics to medicine.

The Struggles for Recognition

Despite his monumental contribution, Edmond Albius faced immense challenges in gaining recognition. In 1862, Claude Richard, a French botanist, attempted to claim Edmond’s discovery as his own. Richard argued that he had developed the method years earlier and dismissed Edmond as “an ignorant child” incapable of such innovation. This assertion was not only false but also deeply rooted in the racist ideologies of the time.

Fortunately, Edmond’s former master, Ferréol Bellier-Beaumont, staunchly defended him. In a letter to local officials, Bellier-Beaumont provided detailed accounts of Edmond’s discovery and demonstrated how the young boy had applied his knowledge independently. Thanks to these efforts, Edmond’s role in revolutionizing vanilla cultivation was acknowledged, though not without lingering doubt and prejudice.

Tragically, Edmond never benefited materially from his discovery. Although slavery was abolished in 1848, Edmond lived in poverty for the remainder of his life. Attempts by Bellier-Beaumont to secure a pension for Edmond went unanswered, and he struggled to find steady work in the years following his emancipation. Accused of a crime he did not commit, Edmond spent time in prison, further compounding his hardships. He died destitute at the age of 51 in 1880, leaving behind a legacy that far outweighed the recognition he received during his lifetime.

Honoring Edmond Albius’s Legacy

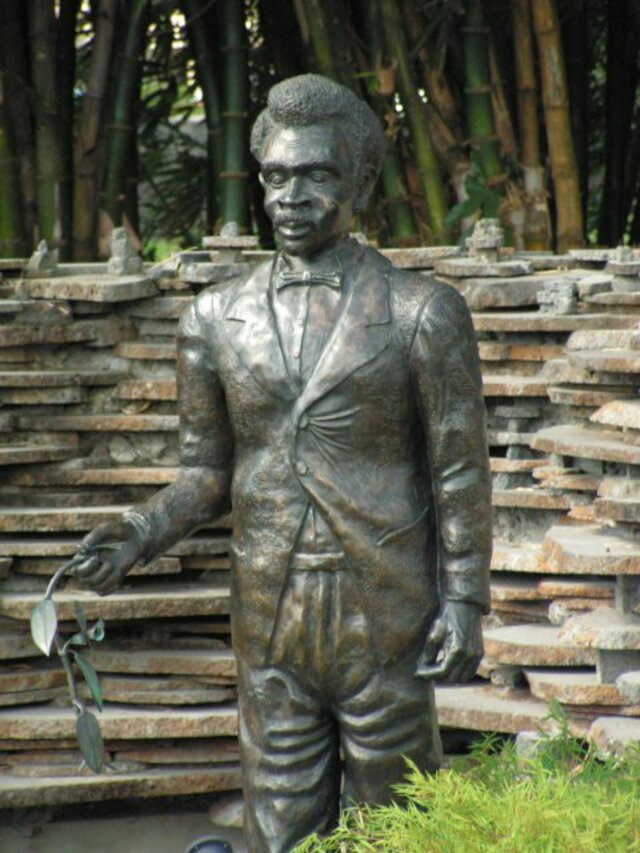

Edmond’s story has slowly gained recognition in recent years. A monument in his honor stands in Sainte-Suzanne, one of Réunion’s oldest towns, and a local school bears his name. However, beyond Réunion Island, Edmond remains largely unknown—a stark contrast to the global reach of his discovery.

A Testament to Human Ingenuity

Edmond Albius’s story is not just about vanilla; it is about the triumph of human ingenuity against the odds. His ability to innovate in the face of systemic oppression highlights the untapped potential of countless individuals whose talents have been suppressed by social and economic hierarchies. Edmond’s discovery continues to touch lives worldwide, reminding us of the profound contributions of marginalized voices in shaping history.

A Call for Recognition

While statues and schools honor Edmond locally, his legacy deserves global recognition. Educating the world about his contributions would not only pay tribute to his genius but also shine a light on the broader injustices of slavery and the exploitation of labor that underpinned colonial economies.

Conclusion

Edmond Albius’s life is a story of brilliance and resilience, set against the backdrop of slavery and colonialism. His revolutionary pollination method transformed vanilla from a rare luxury into a global commodity, shaping economies and industries across continents. Yet, his contributions were overshadowed by prejudice and systemic injustice.

As we savor the sweetness of vanilla today, let us remember the young boy whose ingenuity made it possible. Edmond Albius may have lived a life of hardship, but his legacy endures—a powerful reminder of the resilience of the human spirit and the need to recognize and celebrate the unsung heroes of history.