Hidden beneath the tranquil waters of Germany’s Bay of Mecklenburg lies an extraordinary prehistoric relic: an 11,000-year-old stone wall, one of the earliest hunting structures known to humanity. Discovered by chance in 2021, this remarkable find sheds light on Stone Age ingenuity and reveals the resourcefulness of ancient hunter-gatherers. As one of Europe’s largest early Holocene constructions, this submerged monument offers a rare glimpse into a forgotten era.

The Discovery: A Window into the Past

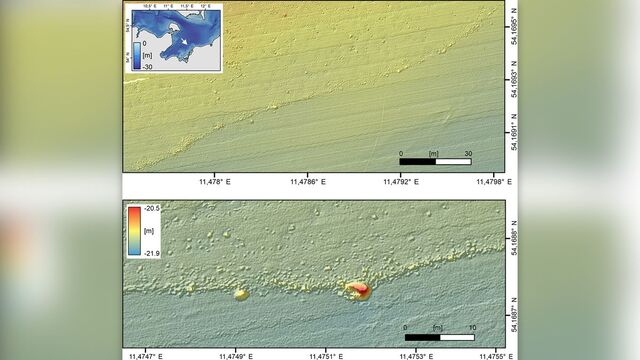

In 2021, marine geophysicists from Kiel University stumbled upon the ancient stone wall during a teaching exercise. While scanning the seafloor with a multibeam echosounder, they detected the unusual structure stretching 975 meters (two-thirds of a mile) along the seabed. Diving to investigate, researchers discovered that the wall was built from 1,670 carefully placed stones, standing 3 feet high and 6.5 feet wide.

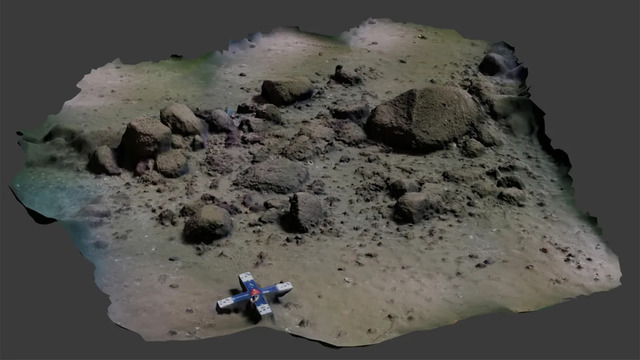

The wall’s location, about 70 feet underwater and 6 miles from Rerik, Germany, suggests it was originally built on dry land. Researchers have since created 3D models using sonar and photogrammetry, revealing its strategic placement near an ancient bog or lake. The site, now submerged due to rising sea levels after the last Ice Age, would have been an ideal hunting ground for reindeer, a primary food source for prehistoric Europeans.

An Ingenious Hunting Strategy

The design of the wall points to its use as a hunting tool. Much like the “desert kites” found in the Middle East, the structure was likely used to corral and trap wild reindeer. Researchers hypothesize that the wall, combined with the natural barrier of a bog or lake, funneled herds into a confined area where hunters could easily kill them. Certain segments of the wall may have served as “blinds,” allowing hunters to hide from their prey.

The wall’s construction highlights the ingenuity of early humans. Its strategic placement and the effort required to build such a massive structure indicate advanced planning and cooperation within the hunter-gatherer community.

The Wall’s Environmental and Historical Context

The wall dates back to the early Holocene, a period following the last Ice Age when humans began to adapt to changing climates and landscapes. During this time, melting ice sheets caused sea levels to rise, transforming what was once fertile hunting land into the submerged landscapes of today. The Bay of Mecklenburg wall was likely submerged around 8,500 years ago, along with vast parts of the Doggerland region that once connected Britain to mainland Europe.

Reindeer were abundant in the region during the early Holocene, making them a vital resource for survival. By about 9,000 years ago, reindeer populations in the area had declined, possibly due to environmental changes and overhunting, leading to the eventual abandonment of the wall.

Current and Future Research

Researchers have employed various technologies to study the submerged structure, including sonar mapping, sediment analysis, and direct dives. These methods have confirmed the wall’s human-made origins and its likely purpose as a hunting structure.

Future excavations aim to uncover artifacts buried along the wall’s length, such as tools or bones, which could provide further insights into its construction and use. Such discoveries may also illuminate the daily lives of the people who built and relied on this monumental structure for survival.

Challenges of Submerged Archaeology

Studying underwater sites presents unique challenges. Submerged structures are often difficult to access, and the process of excavation requires specialized equipment and expertise. However, underwater environments can also help preserve artifacts, as low oxygen levels slow the decay of organic materials. The Bay of Mecklenburg’s relatively calm waters offer ideal conditions for research compared to the turbulent North Sea, where similar submerged sites are threatened by storms and waves.

This discovery underscores the importance of exploring submerged landscapes, many of which remain “Terra Incognita”—uncharted territories holding untold secrets about humanity’s past.

Broader Implications

The 11,000-year-old stone wall is more than just a hunting structure; it is a testament to the adaptability and ingenuity of early humans. Its construction demonstrates sophisticated planning and social organization, while its use highlights the deep connection between prehistoric communities and their environment.

The find also has significant implications for understanding submerged prehistoric sites. As global sea levels rise, many of these ancient landscapes face the risk of being permanently lost. This discovery serves as a reminder of the need to preserve and study such sites, which hold invaluable clues to our shared history.

Conclusion

The submerged stone wall in Germany’s Bay of Mecklenburg stands as a silent witness to the resourcefulness and resilience of early humans. Built to harness the natural environment for survival, this 11,000-year-old structure bridges the gap between our distant past and present understanding. As researchers continue to study this remarkable find, they unlock stories of ingenuity, adaptation, and collaboration—proof that even in the Stone Age, humanity’s ingenuity was boundless.