In a groundbreaking discovery, researchers have uncovered evidence that shifts the timeline of human arrival in Tasmania back by 2,000 years. Ancient sediment cores from islands in the Bass Strait reveal that fire management practices were being conducted 41,600 years ago, predating the oldest known archaeological evidence in the region. This discovery not only redefines the history of human settlement in Tasmania but also highlights the sophisticated environmental practices of the Palawa/Pakana people, demonstrating the deep relationship between Indigenous communities and their land.

The Discovery: Sediment Cores and Ancient Fire

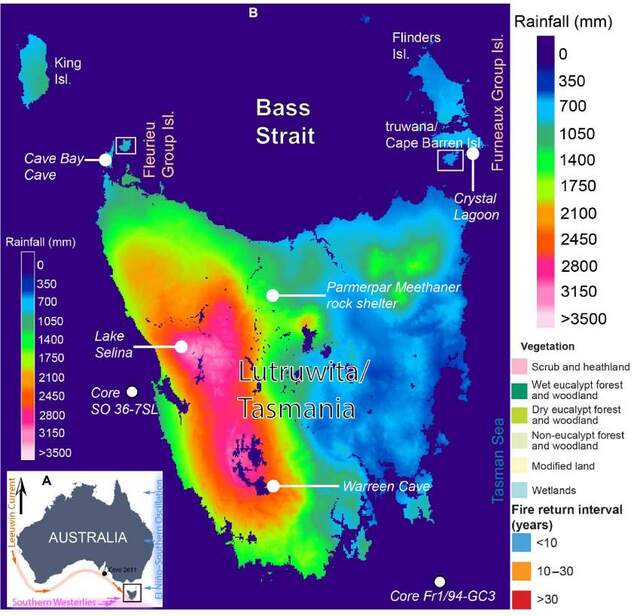

The study, published in Science Advances, centers on two sediment cores collected from Three Hummock Island and Clarke Island, situated north of Tasmania. These islands were once part of a land bridge connecting Tasmania to mainland Australia, forming the ancient continent of Sahul. Researchers, guided by Palawa/Pakana rangers, extracted one core measuring 3 meters deep and another 4 meters deep.

Over tens of thousands of years, pollen and charcoal from the surrounding environment accumulated layer by layer within the sediment, providing a unique historical record. Radiocarbon dating revealed that these cores extended back over 50,000 years, significantly longer than most other records in the region. This exceptional preservation offered researchers a rare opportunity to analyze ancient vegetation and fire patterns.

Video:

Evidence of Human Fire Management

The most striking finding was a sharp increase in charcoal deposits dated to 41,600 years ago, accompanied by changes in pollen that indicated a shift in vegetation. Lead author Dr. Matthew Adeleye, from the University of Cambridge, concluded that this evidence suggests early humans were intentionally burning forests to clear land.

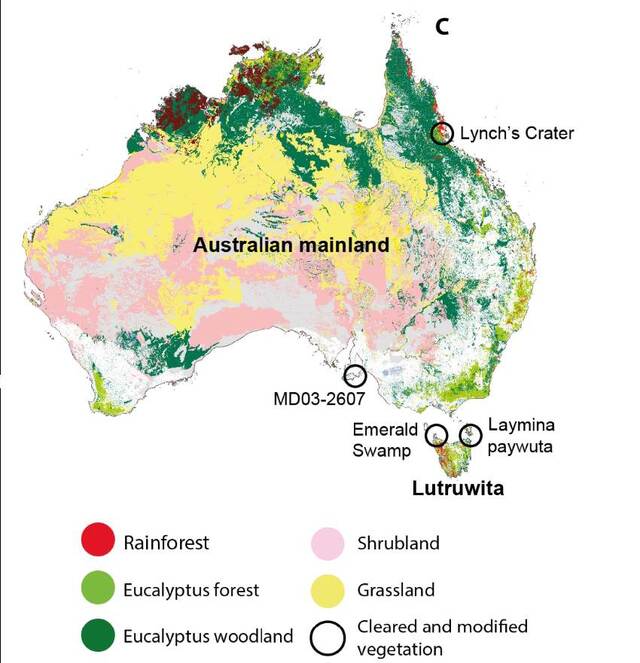

“These early inhabitants were clearing forests by burning them, in order to create open spaces for subsistence and perhaps cultural activities,” Adeleye explained. This aligns with similar studies on mainland Australia, where human arrival is linked to fire regimes that transformed dense forests into grasslands.

Notably, the vegetation changes observed in the sediment cores were nuanced, differing between the wetter western regions and the drier eastern regions of the Bass Strait. This variation highlights the adaptive nature of Indigenous fire practices, tailored to specific ecosystems.

Cultural Burning Practices: A Legacy of Land Stewardship

Indigenous Australians, including the Palawa/Pakana people, have long practiced cultural burning as a means of caring for the land. These fires were not random or destructive but deliberate and controlled, designed to maintain ecological balance. By selectively burning certain areas, they opened up grasslands, promoted biodiversity, and reduced the risk of large, uncontrolled bushfires.

Professor Simon Haberle, a palaeoecologist at the Australian National University and co-author of the study, emphasized the sophistication of these practices. “Aboriginal burning regimes are not just widespread and random, but much more adapted to specific vegetation types and caring for Country in these different regimes,” he noted.

The findings affirm the longstanding Indigenous knowledge of fire management, which is now being reintroduced in many parts of Australia to mitigate the severity of modern bushfires.

Linking the Past to the Continent of Sahul

During the time of these fire practices, Tasmania was not an island but part of the larger landmass of Sahul, which connected it to mainland Australia. This land bridge allowed the Palawa/Pakana people to migrate southward, making them the southernmost inhabitants of the world at the time.

Their arrival marked a significant cultural and ecological shift. The transformation of dense forests into open grasslands through fire not only supported their subsistence activities but also shaped the region’s biodiversity. This interplay between human activity and the environment underscores the profound impact of Indigenous land management practices.

Implications for Archaeological Timelines

This discovery pushes the timeline of human arrival in Tasmania back by 2,000 years, predating the oldest archaeological evidence previously found. Until now, the earliest signs of human settlement in the region were dated to approximately 39,000 years ago.

The new findings challenge conventional archaeological narratives and suggest that Indigenous Australians reached and began managing the Tasmanian landscape far earlier than believed. This has significant implications for our understanding of early human migration, settlement patterns, and environmental interactions.

Modern Relevance of Cultural Burning

In recent years, there has been a renewed focus on reintroducing cultural burning practices across Australia. These traditional methods, developed over tens of thousands of years, offer a sustainable approach to land management and bushfire prevention.

“The Western science information is really more of an affirmation that cultural burning and care for Country has been a feature of the landscape for many, many thousands of years,” Haberle explained. The findings from Tasmania provide further evidence of the effectiveness and longevity of these practices.

By integrating ancient Indigenous knowledge with modern science, researchers and land managers can create more resilient ecosystems capable of withstanding climate challenges.

Future Research Directions

The study of sediment cores in Tasmania is just the beginning. Researchers aim to expand their work to other regions, analyzing additional environmental records to paint a more comprehensive picture of early human activity.

Advances in technology, such as high-resolution pollen and charcoal analysis, will allow for even more detailed reconstructions of past environments. Collaboration with Indigenous communities will remain central to these efforts, ensuring that cultural knowledge continues to inform scientific discoveries.

Conclusion

The discovery of ancient fire management practices dating back 41,600 years redefines our understanding of human arrival in Tasmania and highlights the deep connection between Indigenous Australians and their land. Through controlled burns, the Palawa/Pakana people shaped the environment, creating sustainable ecosystems that supported their communities for millennia.

This research not only sheds light on the past but also offers valuable lessons for the future. By embracing the wisdom of cultural burning, we can work towards a more harmonious relationship with the environment, honoring the legacy of those who came before us.