A groundbreaking study has shed light on the remarkable social and cultural strategies of Europe’s last hunter-gatherer communities. Despite living in small groups with limited population sizes, these ancient societies developed sophisticated mechanisms to avoid inbreeding. Published in the journal PNAS, the research provides valuable insights into the social dynamics and adaptability of these prehistoric groups, revealing a complex web of relationships that extended far beyond biological kinship.

The Genomic Analysis

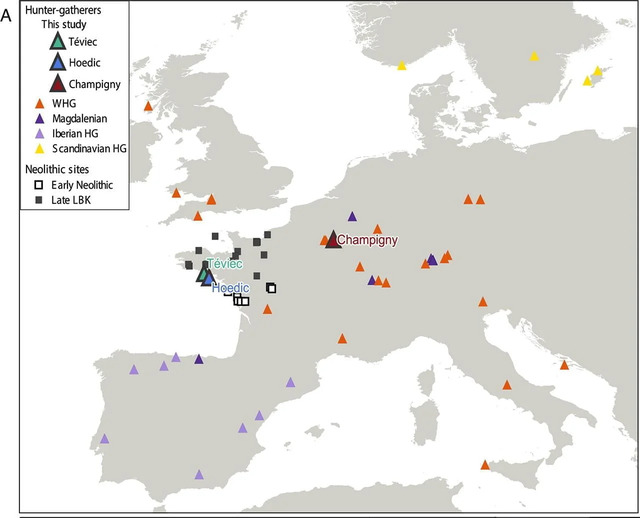

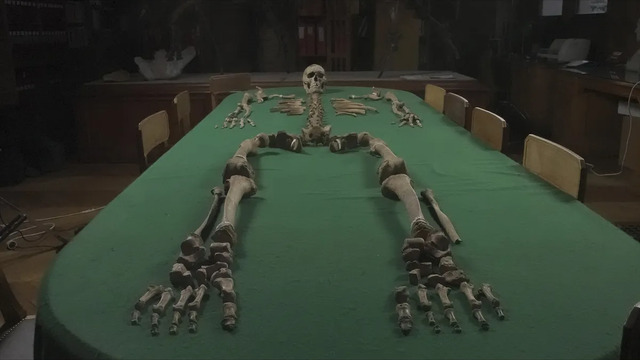

The study, conducted by researchers from Uppsala University in Sweden, focused on the genomes of 10 individuals from burial sites in France, including Téviec, Hoedic, and Champigny. These individuals, who lived between 8,300 and 6,760 years ago, were among the last hunter-gatherers in Europe, coexisting alongside newly arrived Neolithic farming communities.

Using advanced genomic techniques, the researchers were able to determine the biological relatedness of the individuals and analyze their genetic makeup. The findings challenged previous assumptions about the composition of these communities, revealing a surprising lack of close familial ties.

Key Findings

One of the most striking discoveries was the absence of inbreeding within these small, isolated groups. “Our genomic analyses show that although these groups were made up of few individuals, they were generally not closely related,” explains Luciana G. Simões, the lead researcher.

Contrary to earlier theories, the study found no evidence that these communities assimilated women from neighboring farming populations. Instead, they primarily interbred with other hunter-gatherer groups, maintaining distinct genetic identities. This suggests that these communities had developed effective strategies to ensure genetic diversity, even in the face of limited population sizes.

Social Bonds Beyond Kinship

The research also revealed the importance of non-biological social bonds within these ancient communities. In several cases, individuals buried together, such as women and children, were found to have no biological relationship. “This suggests that there were strong social bonds that had nothing to do with biological kinship and that these relationships remained important even after death,” says Dr. Amélie Vialet, a co-author of the study.

These findings highlight the complex social structures of hunter-gatherer groups, where community cohesion and mutual support likely played a crucial role in survival. Burial practices, which often included unrelated individuals, underscore the significance of these bonds in maintaining group stability and avoiding inbreeding.

Cultural Strategies and Their Implications

The study suggests that hunter-gatherer communities employed various cultural strategies to prevent inbreeding. One possibility is the practice of exogamy, where individuals married or formed partnerships outside their immediate group. Another is increased group mobility, which would have facilitated interactions with other hunter-gatherer communities and the exchange of genetic material.

These strategies reflect the adaptability and intelligence of these societies, which recognized the dangers of inbreeding and took steps to mitigate them. By fostering connections with other groups and prioritizing social bonds over biological ties, they were able to maintain genetic diversity and ensure their long-term survival.

Broader Impact and Future Research

The findings have significant implications for our understanding of ancient population dynamics. They challenge earlier assumptions about interactions between hunter-gatherers and Neolithic farmers, suggesting that these groups maintained distinct social and genetic identities despite living in close proximity.

“This study provides a unique opportunity to analyze these groups and their social dynamics,” says Professor Mattias Jakobsson, who led the research. By examining the genomic data alongside archaeological evidence, the researchers have opened new avenues for exploring the complexities of ancient societies.

Future research could expand on these findings by examining similar patterns in other regions or time periods. Advanced techniques, such as DNA analysis and isotopic studies, could provide further insights into the migration patterns, dietary habits, and social structures of prehistoric populations.

Conclusion

The study of Europe’s last hunter-gatherers offers a fascinating glimpse into the resilience and ingenuity of these ancient communities. By developing cultural strategies to avoid inbreeding and fostering strong social bonds, they were able to thrive in challenging environments. These findings not only reshape our understanding of prehistoric societies but also highlight the enduring importance of social connections in human history. Through their innovative practices and adaptability, Europe’s last hunter-gatherers left a legacy of survival and cooperation that continues to inspire us today.