Nestled in the rugged Zagros Mountains of Iraqi Kurdistan, the fortress of Rabana-Merquly has revealed its secrets to archaeologists, unearthing a site of immense historical and spiritual significance. Recent excavations have provided compelling evidence that this fortress served as a sanctuary dedicated to the ancient Persian water goddess Anahita, offering a glimpse into the religious and cultural dynamics of the Parthian Empire over 2,000 years ago.

The Fortress of Rabana-Merquly: A Historical and Geopolitical Marvel

Located in the Zagros Mountains, the Rabana-Merquly fortress played a vital role in the Parthian Empire, which once spanned vast territories from Mesopotamia to modern-day Iran. Its strategic location allowed it to serve as a regional administrative center and a defensive stronghold. But recent discoveries suggest the fortress had a dual purpose: it was not only a military outpost but also a religious sanctuary.

Excavations led by Dr. Michael Brown from Heidelberg University have uncovered architectural remnants, including a seasonal waterfall that appears to have been incorporated into the complex. The natural cascade aligns symbolically with Anahita, a goddess associated with water, fertility, and healing. The proximity of the waterfall to architectural elements and an altar-like sculpture bolsters the hypothesis that Rabana-Merquly was a sacred site.

Anahita: The Divine Source of Earthly Waters

Anahita, often portrayed as a majestic figure in Zoroastrian texts, embodies purity, abundance, and the power of flowing water. During the Seleucid and Parthian periods, she held significant cultural and religious importance. Sanctuaries dedicated to her often featured water elements, such as rivers or springs, symbolizing her divine essence.

The Avesta, Zoroastrianism’s sacred text, describes Anahita as capable of transforming into cascading streams or waterfalls. This symbolic imagery is reflected in the design of Rabana-Merquly, where the waterfall seems to have been an integral part of the sanctuary. Researchers suggest that rituals involving water and fire—two key elements in Zoroastrian worship—may have been performed here.

Architectural and Archaeological Clues

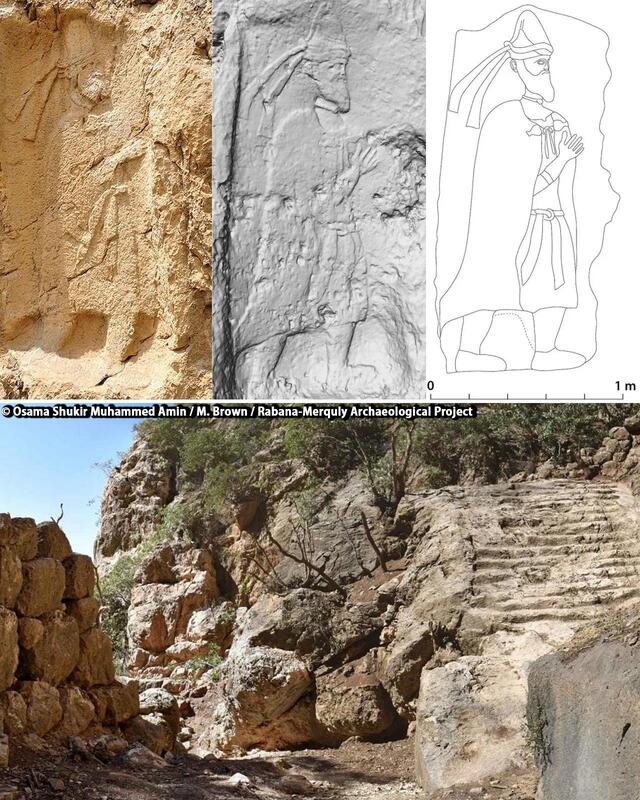

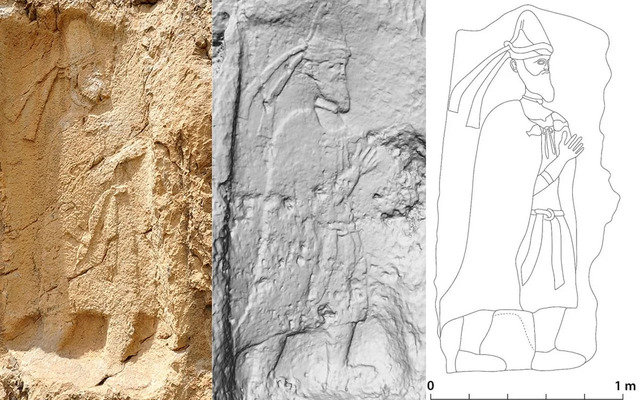

The fortress itself spans a significant area, with steep staircases, defensive walls, and remnants of pathways leading to the sanctuary. Key discoveries include a rock relief near the fortress entrance depicting a figure that may represent an ancient ruler or divine intermediary. This relief, along with the proximity to the altar-like structure, suggests that Rabana-Merquly served as both a religious and political hub.

Dr. Brown’s team also identified extensions to the fortress surrounding the waterfall. The presence of these structures indicates the area was more than just a utilitarian space; it was likely imbued with spiritual significance. The altar-like sculpture, possibly used for burning offerings or oil, aligns with traditional practices in sanctuaries dedicated to Anahita.

Religious and Dynastic Significance

The hypothesis of an Anahita sanctuary gains further weight when considering the broader religious and political context of the Parthian Empire. During this period, rulers often established dynastic cults at sacred sites, using them to honor their ancestors and legitimize their reign.

Dr. Brown posits that Rabana-Merquly may have absorbed a pre-existing shrine, integrating it into the Anahita cult. This practice of reusing and repurposing sacred sites was common in ancient civilizations, allowing new rulers to assert continuity with past traditions while solidifying their authority.

Cultural Symbolism in the Parthian Era

The sanctuary at Rabana-Merquly offers a glimpse into the intricate interplay between religion and geopolitics in the Parthian era. While few direct comparisons exist, the findings at Rabana-Merquly provide a unique opportunity to study the symbolic and practical roles of water and fire in Zoroastrian worship.

The Rabana-Merquly site also highlights the cultural significance of Anahita, whose worship was deeply intertwined with the natural landscape. By incorporating the seasonal waterfall into the sanctuary, the Parthians emphasized their reverence for Anahita as a life-giving force. The discovery of ritualistic elements such as the altar reinforces this connection.

Challenges and Future Discoveries

Despite its historical importance, Rabana-Merquly remains relatively underexplored. The lack of direct archaeological parallels complicates efforts to fully understand the site’s significance. However, the recent excavations, funded by the German Research Foundation and conducted in collaboration with the Directorate of Antiquities in Slemani, represent a promising step forward.

Dr. Brown’s research has already shed light on the religious practices of the Parthian era, but much remains to be uncovered. Ongoing studies aim to document the extent of the sanctuary, analyze its architectural features, and uncover additional artifacts that may provide further insights into its use.

Conclusion

The discovery of a potential Anahita sanctuary within the fortress of Rabana-Merquly is a testament to the enduring legacy of the Parthian Empire and its religious traditions. The site not only highlights the spiritual importance of water and fire in Zoroastrian practices but also offers a window into the complex interplay between religion, politics, and culture during this period.

As excavations continue, Rabana-Merquly promises to reveal even more about the lives and beliefs of those who once walked its pathways. For now, it stands as a remarkable example of how ancient communities shaped their landscapes to reflect their spiritual and cultural values, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inspire and intrigue.