London Bridge, completed in 1209, was more than a river crossing; it was a thriving medieval community. With around 500 residents living in homes, shops, and chapels built on the bridge, it became a hub of activity and ingenuity. Despite facing fires and collapses, it stood as a testament to engineering brilliance and the resilience of London’s people.

The Only Crossing: Historical Importance

For much of its existence, London Bridge was the only fixed crossing of the Thames in the heart of England’s capital. Until the construction of Fulham Bridge in 1729, it served as a crucial link between the City of London and Southwark, connecting commerce, culture, and communities. The bridge’s importance extended beyond mere utility; it became a lifeline for trade and movement, shaping the city’s development.

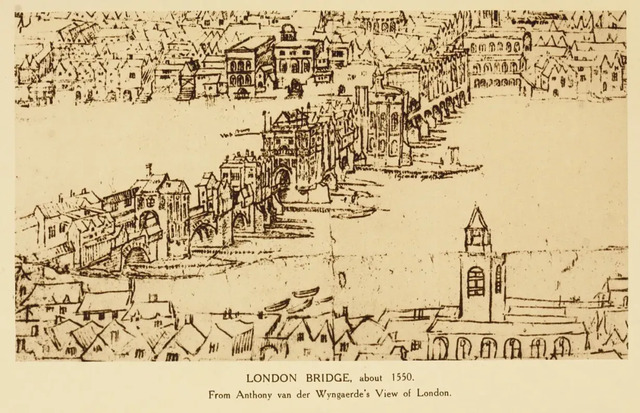

Constructed about 150 feet east of the present-day London Bridge, the medieval version replaced an earlier wooden bridge. This new stone structure symbolized the era’s architectural ambition, showcasing England’s shift toward more permanent and robust infrastructure.

Video:

The Feat of Engineering

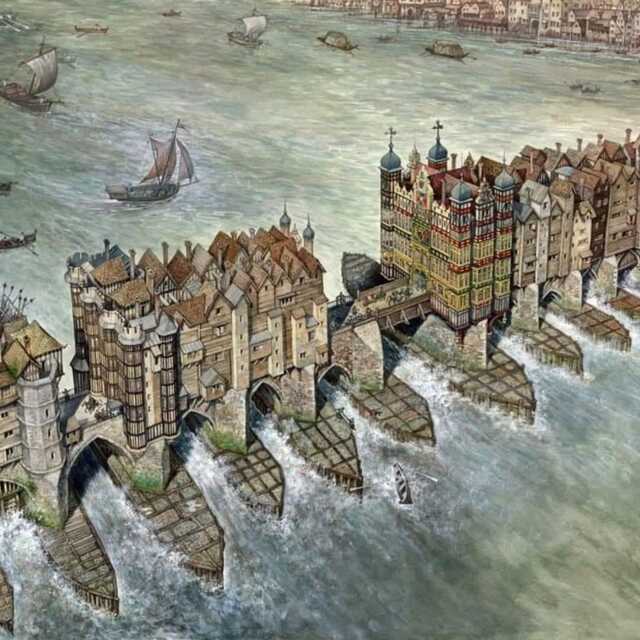

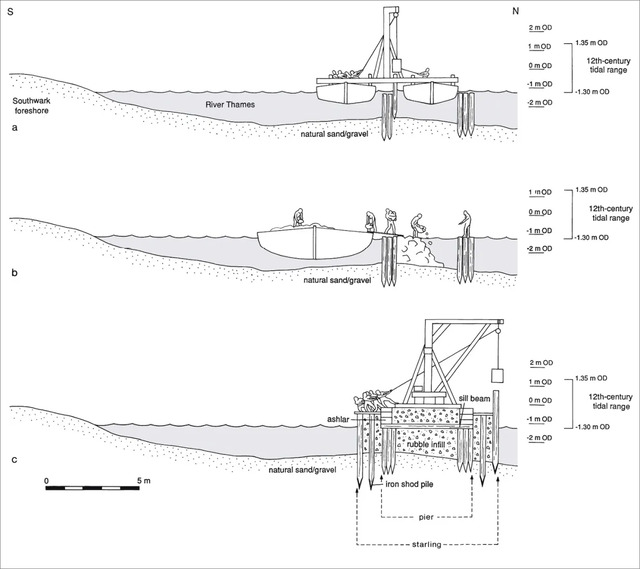

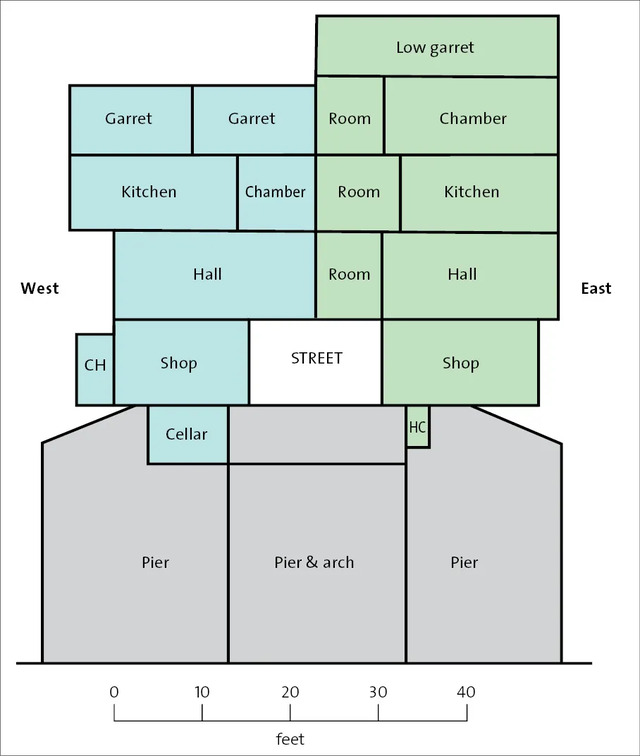

Building a bridge over a tidal river as wide and forceful as the Thames was no small feat. The construction, overseen initially by Peter of Colechurch, began with the driving of timber piles into the riverbed to create enclosures filled with rubble for the bridge’s foundations. These piers were topped with starlings—massive cutwaters designed to protect the bridge from the river’s relentless currents. Despite its strength, the bridge required constant maintenance due to the immense force of the water flowing through its narrow arches.

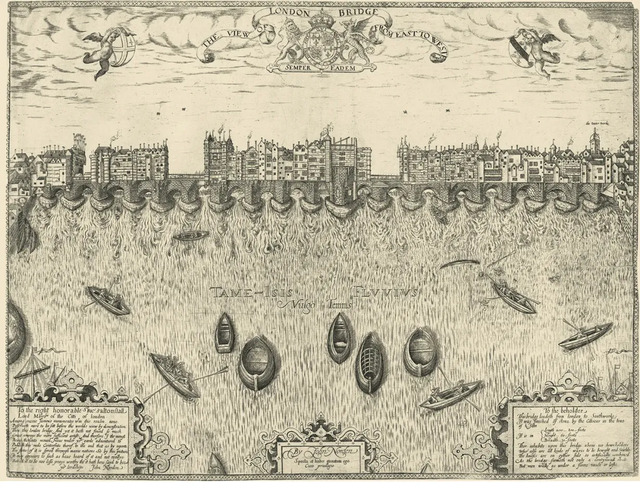

The bridge consisted of 19 stone piers supporting arches that averaged 24 feet in width, allowing a sturdy platform for the houses, shops, and even a chapel that would eventually rise above.

Surviving Fires, Floods, and Collapses

Remarkably, London Bridge survived two major fires and several structural collapses during its long life. Fires in 1212 and 1633 ravaged parts of the bridge, while sections collapsed in 1281 and 1437 due to floods and foundational weaknesses. Despite these challenges, the bridge’s robust construction allowed it to be repaired and modified repeatedly, ensuring its continued use for centuries.

The famous nursery rhyme “London Bridge is Falling Down” is often associated with this medieval structure, though it likely refers to various bridges across Europe. Its enduring presence in folklore only adds to the mystique of the bridge’s history.

Life on the Bridge: A Medieval Town

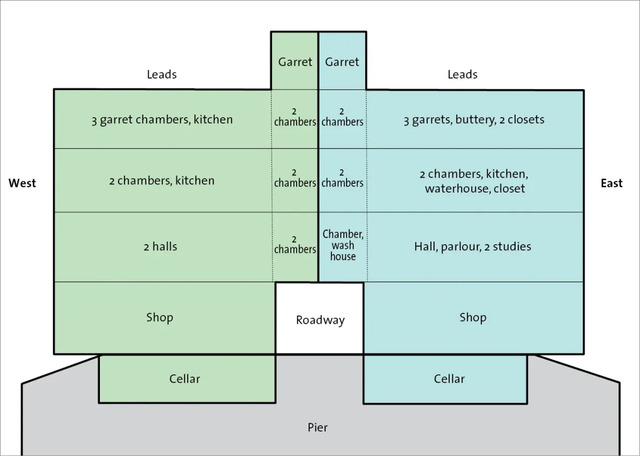

Inhabited bridges were a common feature in medieval Europe, and London Bridge was no exception. By the 14th century, the bridge was home to around 140 properties, ranging from small shops to spacious five-story houses with cellars and garrets. This community of roughly 500 people was akin to a small town, complete with tradespeople, merchants, and families.

The bridge’s unique setting offered both opportunities and risks. Residents and shopkeepers benefited from the constant flow of travelers and goods, but the narrow structure and proximity to the water made life precarious, especially during floods or fires.

Bridge Houses and Their Unique Design

The houses on London Bridge were architectural feats in themselves. Most extended beyond the bridge’s edges, supported by timber beams that jutted out from the stone piers. These overhanging structures made efficient use of the limited space and created a visually striking streetscape.

A typical property might include a shop on the ground floor, living quarters above, and storage or workspaces in the basement. Some larger houses spanned the width of the bridge, creating tunnel-like passages for pedestrians and carts below. This alternating pattern of open and enclosed spaces gave the bridge a distinctive rhythm and character.

The Role of Bridge House Charity

The management and maintenance of London Bridge fell to a medieval charity known as Bridge House. Initially overseen by the chapel’s clergy, this responsibility later passed to appointed wardens from the city. Rent from the houses and tolls on crossing carts and boats funded the bridge’s upkeep.

Bridge House played a crucial role in ensuring the bridge’s longevity, and its legacy continues today. The charity now supports several modern London bridges, a testament to the enduring impact of this medieval institution.

Trade and Commerce on the Bridge

In its early years, London Bridge was a hub for specialized trades. Haberdashers, glovers, cutlers, bowyers, and fletchers dominated the commercial landscape, selling goods that required skill and craftsmanship. Over time, these trades gave way to cloth merchants, booksellers, and stationers, reflecting broader shifts in London’s economy.

The bridge’s shops catered to both locals and travelers, offering everything from tools and textiles to books and religious artifacts. Despite its bustling activity, the bridge lacked street vendors and food sellers, likely due to the risks posed by fire.

Religious and Regal Structures

Three major structures defined the medieval bridge: the chapel of St. Thomas, the drawbridge tower, and the Stone Gate. The chapel, dedicated to St. Thomas Becket, served as both a place of worship and a starting point for pilgrimages to Canterbury. After the Reformation, it was converted into a house, marking a shift in its function.

The drawbridge tower played a defensive role, complete with a portcullis and space to display the heads of executed traitors—a grim reminder of the era’s harsh justice. Meanwhile, the Stone Gate at the Southwark end of the bridge served as a symbolic and literal gateway to the city.

Waterworks and Public Infrastructure

London Bridge was more than just a crossing; it was also a source of public utilities. In the late 16th century, Dutch engineer Peter Morris installed a water wheel beneath one of the arches to pump water to nearby homes. This innovative system, along with public latrines and grinding mills, demonstrated the bridge’s multifaceted role in urban life.

The Decline and Demolition of the Medieval Bridge

By the 18th century, the bridge’s narrow arches and aging infrastructure had become obstacles to both river traffic and urban growth. In 1761, all houses on the bridge were removed, and by 1831, a new five-arch bridge designed by John Rennie replaced the medieval structure. The demolition of the old bridge marked the end of an era, but its legacy lives on in history and legend.

Conclusion

London Bridge was far more than a means of crossing the Thames; it was a living, breathing community that thrived for over 600 years. Its combination of engineering brilliance, architectural creativity, and vibrant human activity made it a unique and enduring symbol of medieval life. Though the medieval bridge is gone, its story continues to captivate us, reminding us of a time when life across the water was as rich and complex as the city it served.