In a fascinating glimpse into the ancient past, scientists have uncovered what may be the world’s oldest recorded instance of a squid-like creature attacking its prey. This remarkable fossil, dating back nearly 200 million years, offers unprecedented insight into predatory behaviors of prehistoric marine life. Discovered on the Jurassic coast of southern England in the 19th century, this fossil is now housed within the collections of the British Geological Survey in Nottingham.

Discovery and Analysis

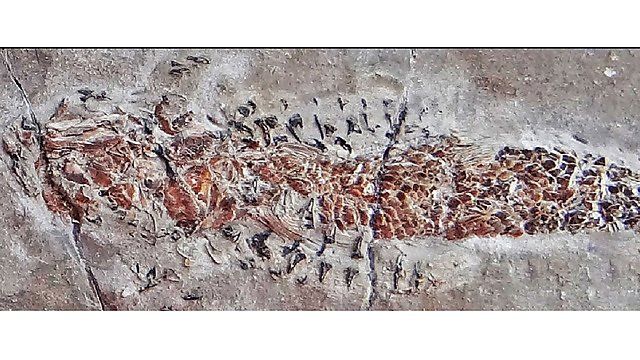

The fossil under scrutiny is identified as Clarkeiteuthis montefiorei, a squid-like cephalopod. The specimen reveals this ancient creature in the act of attacking a herring-like fish, Dorsetichthys bechei. The positioning of the squid’s arms around the fish’s body suggests that this scenario is not merely a quirk of fossilization but a genuine representation of a predatory event.

The fossil has been dated to the Sinemurian period, which spans from approximately 190 to 199 million years ago. This dating pushes the record of such predatory behavior back by over 10 million years from previously known examples.

The research team, led by the University of Plymouth in collaboration with the University of Kansas and the Dorset-based company The Forge Fossils, has submitted their findings to the Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association. Their work will also be featured in Sharing Geoscience Online, a virtual platform that serves as an alternative to the European Geosciences Union’s annual General Assembly.

Implications and Insights

Professor Malcolm Hart, Emeritus Professor at Plymouth and the study’s lead author, highlighted the significance of this fossil. “The Blue Lias and Charmouth Mudstone formations of the Dorset coast have yielded numerous important body fossils since the 19th century. This fossil is particularly extraordinary, as predation events are rarely found in the geological record,” he stated. The fossil suggests a violent encounter that likely led to the death and subsequent preservation of both creatures.

The researchers have proposed two primary hypotheses regarding how the animals came to be preserved together. One possibility is that the fish was too large for its predator or became ensnared in its jaws, leading both animals to settle on the seafloor where they were preserved. Alternatively, the Clarkeiteuthis may have carried its prey to the seafloor as a strategic move to avoid other predators. In this scenario, the squid might have suffocated in low-oxygen waters, leading to the preservation of both animals.

Conclusion

The discovery of this 200-million-year-old fossil provides a rare and vivid snapshot of ancient marine life. It not only extends our understanding of cephalopod predation but also highlights the extraordinary conditions required for such fossils to form. As researchers continue to explore these ancient remains, they uncover deeper insights into the complex dynamics of prehistoric ecosystems. This finding underscores the importance of fossil records in piecing together the history of life on Earth and offers a captivating glimpse into the violent interactions that shaped ancient marine environments.