In the cold expanses of Ice Age Alaska, a bond was formed that would redefine the survival strategies of early humans. Recent archaeological discoveries reveal that the relationship between humans and canines in the Americas dates back at least 12,000 years—2,000 years earlier than previously believed. These findings shed light on how the ancestors of modern dogs, or possibly tamed wolves, played a crucial role in shaping the lives and livelihoods of Indigenous peoples.

Historical Context

The Americas 12,000 years ago were marked by a challenging landscape at the end of the Ice Age. Indigenous communities adapted to this environment through resourceful partnerships with nature. Among these partnerships was the emerging bond between humans and canines. Archaeological work in Alaska’s Tanana Valley has provided invaluable insights into this connection, thanks to ongoing research efforts and collaborations with Indigenous communities.

The Tanana Valley has been a focus of archaeological inquiry since the 1930s. It is here that researchers recently unearthed the remains of ancient canines, revealing their integral role in early human societies. These findings, supported by the Healy Lake Village Council and local Indigenous leaders, underscore the importance of ethical collaboration in uncovering the past.

Video:

Key Findings

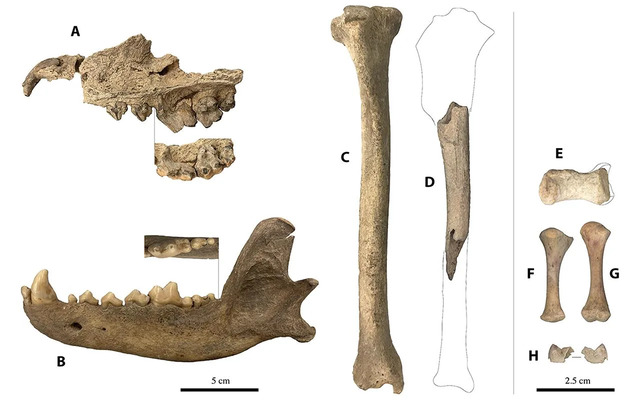

A team led by Dr. François Lanoë from the University of Arizona made groundbreaking discoveries at two archaeological sites in Alaska. The first, a 12,000-year-old canine tibia found at Swan Point, stands as one of the earliest pieces of evidence of human-canine interactions in the Americas. Radiocarbon dating confirmed its age, situating it within a period when humans were navigating the challenges of a changing climate.

The second discovery, an 8,100-year-old canine jawbone unearthed at Hollembaek Hill, adds to this story. Both bones exhibit signs of potential domestication. However, the standout finding came from chemical analysis: traces of salmon proteins were detected in the diet of these ancient canines. This dietary reliance on salmon, likely provided by humans, indicates a level of dependence that suggests domestication or at least a close association with people.

Evidence of Domestication

The presence of salmon proteins in the canine remains marks a significant breakthrough. As archaeologist Ben Potter explains, wild animals typically do not hunt salmon in large quantities, particularly in the challenging environments of Ice Age Alaska. The consistent presence of this dietary element strongly suggests that these canines were fed by humans.

This behavior aligns with the characteristics of domesticated animals, which rely on humans for sustenance. However, genetic analysis reveals a surprising twist: these ancient canines are not directly related to modern dog populations. This raises the possibility that these animals were tamed wolves rather than fully domesticated dogs, offering a nuanced view of early human-canine relationships.

Genetic Analysis and Insights

The genetic data from these ancient remains offer a fascinating perspective. Despite their behavior resembling that of domesticated dogs, these canines bear no genetic connection to the modern breeds we know today. This disconnect has led researchers to hypothesize that the animals found at Swan Point and Hollembaek Hill were either early branches of domestication that did not lead to modern breeds or represented a separate experiment in taming wild wolves.

Dr. Lanoë emphasizes the significance of these findings: “Until you find those animals in archaeological sites, we can speculate about it, but it’s hard to prove one way or another. So, this is a significant contribution.”

Indigenous Partnerships

Integral to this research was the partnership with the Healy Lake Village Council, representing the Mendas Cha’ag people. Archaeologist Evelynn Combs, a Healy Lake member, highlights the importance of obtaining proper permissions and respecting the land’s stewards.

For the Mendas Cha’ag people, dogs have long been companions and collaborators in daily life. Combs notes that nearly every resident in her village shares a close bond with a dog, a tradition that dates back millennia. These cultural practices reflect a deep understanding of human-canine relationships and their role in survival and community cohesion.

Broader Implications

The discoveries in Alaska underscore the critical role of canines in early human survival. These animals were not merely companions; they were integral to hunting, transportation, and security. By forging bonds with these creatures, humans gained an adaptive edge in the harsh environments of the Ice Age.

Furthermore, this research invites reflection on how human-animal relationships continue to shape our lives. From service animals to family pets, the legacy of early domestication is evident in our modern world. These findings also emphasize the importance of fostering respect and collaboration with Indigenous communities, whose knowledge and stewardship are invaluable in uncovering our shared history.

Conclusion

The discovery of ancient canine remains in Alaska provides a profound glimpse into the origins of one of humanity’s most enduring partnerships. These animals, whether tamed wolves or early dogs, were more than companions; they were co-navigators in the journey of survival and adaptation.

As we look back 12,000 years to the bond formed between humans and canines, we are reminded of the power of collaboration—whether between species or between modern researchers and Indigenous communities. This study not only enriches our understanding of the past but also underscores the timeless nature of partnership and mutual support.